All Issues

Hedgerow benefits align with food production and sustainability goals

Publication Information

California Agriculture 71(3):117-119. https://doi.org/10.3733/ca.2017a0020

Published online September 13, 2017

NALT Keywords

Abstract

Restoring hedgerows, or other field edge plantings, to provide habitat for bees and other beneficial insects on farms is needed to sustain global food production in intensive agricultural systems. To date, the creation of hedgerows and other restored habitat areas on California farms remains low, in part because of a lack of information and outreach that addresses the benefits of field edge habitat, and growers' concerns about its effect on crop production and wildlife intrusion. Field studies in the Sacramento Valley highlighted that hedgerows can enhance pest control and pollination in crops, resulting in a return on investment within 7 to 16 years, without negatively impacting food safety. To encourage hedgerow and other restoration practices that enhance farm sustainability, increased outreach, technical guidance, and continued policy support for conservation programs in agriculture are imperative.

Full text

Intensive, homogeneous agricultural lands are highly productive and efficient for meeting global food production demands. However, these fields often have little surrounding natural habitat, which has led to a loss of biodiversity and ecosystem services on farms (MEA 2005), including a reduction of pollinators and other beneficial insects (Zhang et al. 2007). As a result, external inputs, such as honey bee hives and pesticides, are increasingly needed to keep farms profitable, causing widespread concern that our farming systems are not sustainable (Hobbs 2007; Tilman 1999).

Restoring field edges, by creating hedgerows or other habitat plantings, diversifies farms without taking land out of production (Long and Anderson 2010; Williams et al. 2015). Benefits include wildlife habitat creation (Heath et al. 2017), water quality protection (Long et al. 2010) and increased pollination and pest control by beneficial insects (Morandin et al. 2016). Despite the documented benefits, resources (UC IPM 2017), and support for conservation programs through the Agricultural Act of 2014, commonly known as the Farm Bill (NRCS 2017; USDA 2017), field edge habitat restoration on farms remains low.

Adoption of restoration practices is explained in part by landholders' experience with the potential benefits (e.g., wildlife habitat, aesthetics, increased beneficial insects such as natural enemies and bees) and their concerns about habitat plantings (e.g., regulations, equipment movement limitations, potentially increased presence of weeds, rodents and insect pests). The low implementation of restoration highlights the need for technical and financial assistance in local farming communities through conservation programs, such as those in the Farm Bill (Garbach and Long 2017).

A hedgerow bordering an almond orchard in Yolo County has been planted with native flowering shrubs and a forb understory of annual and perennial wildflowers. Hedgerows support bees and other pollinators as well as the natural enemies of pest insects and mites.

UC Agriculture and Natural Resources, UC Berkeley, UC Davis and local conservation groups have been studying hedgerows in the Sacramento Valley for two decades. Research projects have examined pest control, pollination, wildlife, and food safety in row crops and orchards, with and without hedgerows. The results showed field edge habitat provides significant benefits from beneficial insects and poses low risks to crop production from insect pests and rodents (Morandin et al. 2016; Sellers et al. 2016). However, this information alone has not proved sufficient for increasing hedgerow adoption. Garbach and Long (2017) found that hedgerow adoption was highest where there was both agency support (e.g., from Natural Resources Conservation Service) and peer-to-peer support from growers with experience in field edge plantings. Efforts to increase the use of hedgerows on farms may also benefit from strategic support for social learning (e.g., peer-to-peer communication) that highlights the potential benefits and addresses growers' concerns about field edge habitat (Garbach and Long 2017).

The flowers of toyon, a native shrub, are a nectar source for beneficial insects. The berries are favored by birds, including insectivorous birds that feed on crop pests.

Hedgerows data

We synthesized data from our studies in hedgerows and adjacent crops on the provision of two ecosystem services — pollination provided by native bees and pest control by natural enemies. We considered these data within a framework of crop production, wildlife habitat and food safety using processing tomatoes and walnuts as model systems.

We evaluated farm hedgerows near Sacramento in the Central Valley that were 10 to 20 years old during our study years, about 1,000 feet long and 15 feet wide, and planted with California native flowering shrubs and perennial grasses (Long and Anderson 2010). We compared these to conventionally managed field edge cropping systems, which were mowed, disked or sprayed with herbicides to control weeds, though some residual weeds were always present.

Author Rachael Long and grower Justin Rominger walk a hedgerow adjacent to a tomato field in Yolo County. Research suggests that hedgerow adoption is positively influenced by technical support from conservation agencies as well as by grower-to-grower communication.

Improved pest control and pollination

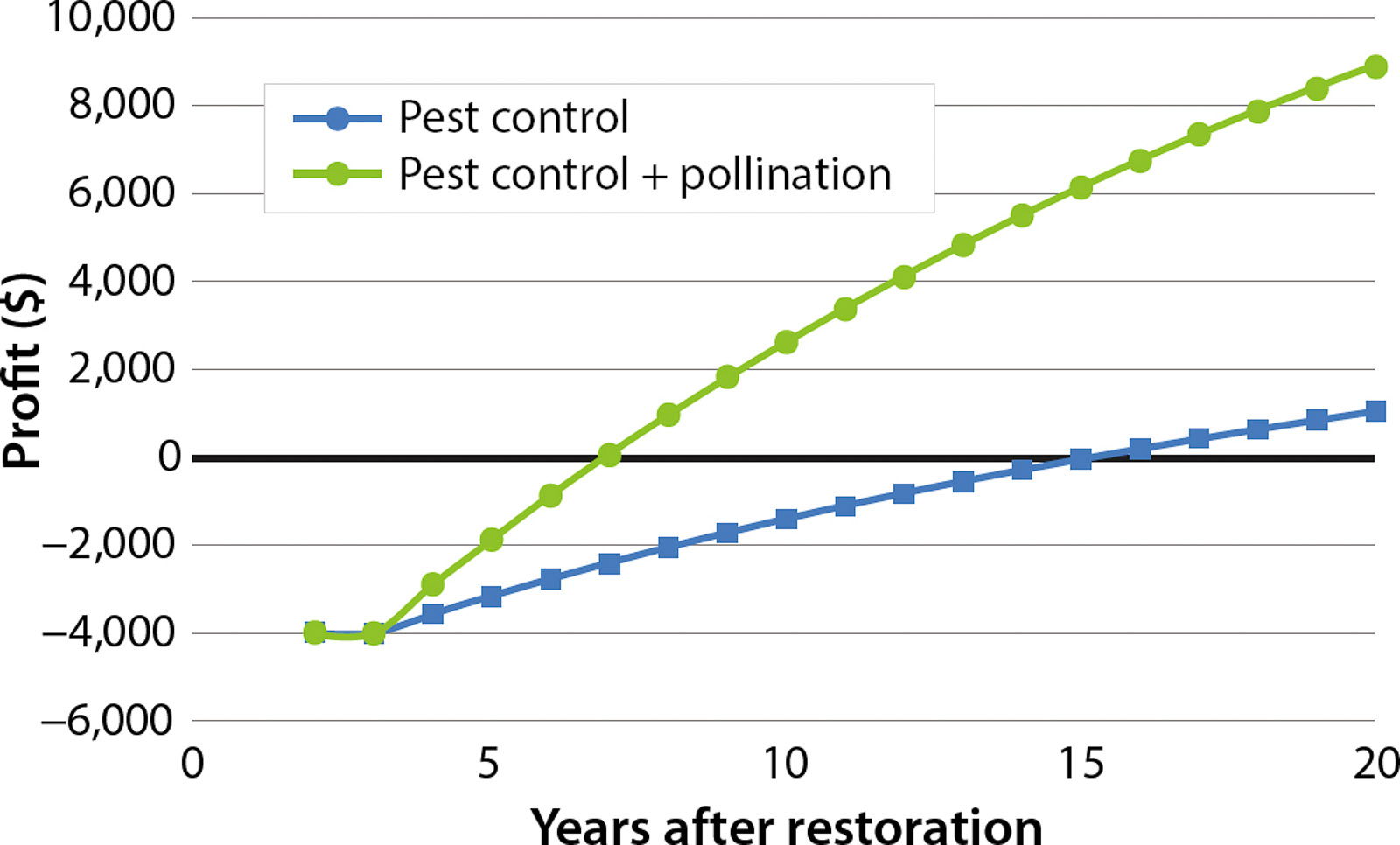

Natural enemy insect numbers were higher in the hedgerows than in the conventionally managed field edges and insect crop pests were lower. Hedgerows also exported natural enemies into adjacent crops, where they provided biocontrol of insect pests (Long et al. 1998; Morandin et al. 2011, 2014). Tomato crops with hedgerows required less input of insecticides than those without them. Considering only the reduction in insecticide treatments, and a cost of $4,000 for hedgerow installation and establishment (Long and Anderson 2010), profit was realized after 16 years (Morandin et al. 2016; fig. 1).

Native bee abundance and diversity were higher in the hedgerows than in the conventionally managed field edges (Morandin and Kremen 2013). Hedgerows also exported native bees into adjacent tomato crops, where sentinel canola (potted plants used to assess pollination effects) had greater bee abundance than sentinel canola plants adjacent to conventionally managed field edges. Hedgerow profit from pollination enhancement in canola and enhanced biocontrol of insect pests was realized after 7 years (Morandin et al. 2016; fig. 1). Our profit model can be adapted to different rotational cropping systems.

Fig. 1. Hedgerow restoration studies showed the value of hedgerows in terms of their pest control and pollination benefits in rotational cropping systems (from Morandin et al 2016).

Minimal impacts on wildlife, food safety

Remote cameras and live trapping of rodents in hedgerows and conventionally managed field edges documented that hedgerows did not generally result in greater mammalian wildlife incursion into field interiors at the walnut and tomato study sites. However, cottontail rabbits were more numerous in the hedgerows, and when they move into adjacent crops they can damage seedling stands.

Above, bees visit wildflowers in a hedgerow: a honey bee on elegant clarkia (Clarkia unguiculata) and a bumble bee on California phacelia (Phacelia californica).

Hedgerows did not have any noticeable impact on foodborne pathogen prevalence, including Salmonella (< 1% of rodents tested positive in walnuts and 0% in tomatoes) and E. coli O157 (0% of rodents in both tomatoes and walnuts) (Sellers et al. 2016). Hedgerows are generally too narrow relative to the larger landscape to have significant influence on vertebrate pests in adjacent crops. These data support other UC studies documenting minimal impacts of field edge habitat and associated wildlife on farms and food safety issues (Jay-Russell 2013; Karp et al. 2015).

The case for hedgerows

There is increasing pressure on farmland to meet the projected increases in the global demand for food, and also pressure to protect limited natural resources (Foley et al. 2011). Hedgerows provide a tool for integrating habitat, conservation and farm production goals without taking land out of production. Our studies showed they can reduce growers' reliance on crop inputs, such as honey bees and insecticides, and support food production. Similarly, global studies on the value of habitat on farms have found benefits to pollination and pest control (Garibaldi et al. 2011; Holland et al. 2017; Kennedy et al. 2013). Research on other benefits associated with field edge habitat, such as more insectivorous birds (Garfinkel and Johnson 2015) and water quality enhancement (Long et al. 2010), might provide an even more comprehensive case for why field edges should be more widely considered and restored to increase farm sustainability.

Farmers and landowners familiar with these benefits were more likely to plant hedgerows on their farms (Garbach and Long 2017). This suggests that farmer perceptions and actions to plant hedgerows can be positively influenced by outreach from conservation agencies (e.g., NRCS) that focus on technical support for field edge plantings. Support from agencies that target early adopters and create demonstration hedgerows is important for the sharing of information from farmer to farmer and neighbor to neighbor to support field edge restoration. Enhancing biodiversity is critical for building resilience in our farming systems to help reduce our reliance on external inputs for crop production.