All Issues

Urban forestry adds $3.8 billion in sales to California economy

Publication Information

California Agriculture 50(1):6-10. https://doi.org/10.3733/ca.v050n01p6

Published January 01, 1996

Abstract

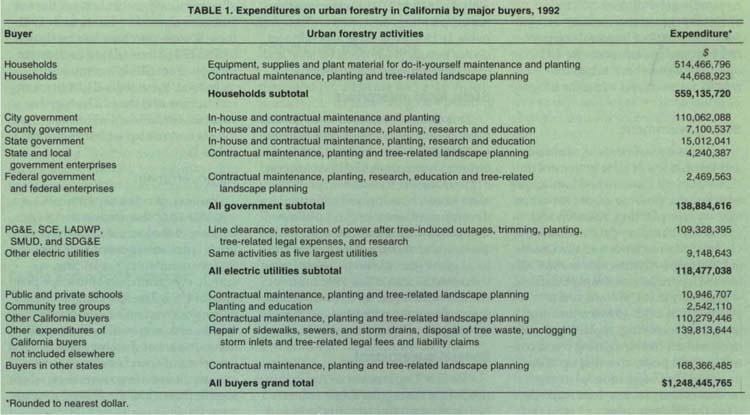

Urban forests provide tree products and aesthetic, recreational, health and environmental benefits. Californians spent at least $1.080 billion to obtain these benefits and the state's urban forestry sector had sales of at least $1.248 billion in a 12-month period in the early 1990s. As a result of ripple effects, urban forestry accounted for at least $3.789 billion in total sales, $2.092 billion in income to individuals, and 64,000 jobs in this period in the state. Knowledge of this economic activity is necessary for voters and government officials who make decisions that affect management of these and other natural resources in California.

Full text

Design and construction of landscapes using trees are among the urban forestry activities that contribute to the economy.

Urban forests, such as public gardens and parks, provide a number of benefits to Californians. These include aesthetic enhancement, recreational opportunities, energy conservation through shade, reduction in local particulate and gaseous pollution, carbon sequestration, noise abatement, better control of water runoff and improved water quality, habitat for wildlife, and tree products, such as firewood, mulch and compost. However, California policy and budgetary decision makers lack quantitative information about the economic activity associated with urban forestry. Sound arboricultural management, particularly in a period of intense competition for water and financial support, requires knowledge of the costs that people in the state incur to secure the benefits of urban forests and the economic impacts of sales of products and services related to these natural resources.

The purpose of this research project was to estimate the subset of costs that represent transactions between buyers and sellers of urban forestry-related products and services in the state and the effects of these transactions on sales, employment and personal income in the state's economy in a given year. Urban, or community, forestry refers to the growing, planting, use, maintenance, removal, disposal and study of trees, usually in incorporated cities, towns and other settlements. Community forestry also refers to activities that are undertaken as a direct consequence of these trees, such as repairs of infrastructure damaged by tree roots. However, urban forestry does not refer to tree-related range management or to the production, distribution or use of timber, other industrial forest products, Christmas decorations or commercial fruit and nut products.

Each monetary transaction involves a buyer and a seller, a purchase and a sale. We focus on the expenditure by major buyers, rather than major sellers, of urban trees and tree-related products and services in 12 months in 1991-1992, 1992, or 1992-1993. We do so because of the ready availability of data from two important surveys: the National Gardening Association's 1992–1993 survey of households and the California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection's 1992 survey of city and county governments and their community and urban tree programs. Our estimates of expenditures by major buyers are also based on two other sources of information: the 1991 IMPLAN databases of regional consumption demand and of sales and purchases of companies in 528 sectors of the California economy, and our own surveys of the 5 largest utilities in the state, 3 state agencies, 14 community tree groups, 2 city governments, and the city arborist in San Jose. With the possible exception of household purchases of tree plants and tree-care equipment from businesses outside the state, the major buyers purchase urban forestry-related products and services from sellers in California. Thus our focus on the buying side still allows us to estimate the sales of sellers who are located in the state.

Sales of related products such as fertilizer, pesticides and gardening equipment also contribute to the economy.

Households

Some households purchase trees as well as fertilizer, pesticides, spades, pruning equipment and water to care for the trees around their houses. The mean 1992 expenditure per household in the Pacific region was $17.32 for do-it-yourself tree-related landscaping, $1.34 for insect control, $24.40 for tree care and $5.17 for fruit trees. These average expenditures by Pacific region households are the best available estimates of average tree-related expenditures of California households. According to the 1992 California Statistical Abstract, the state had 10,667,451 households in 1992. Thus the estimated expenditure of California households for do-it-yourself tree planting, insect controls for trees, tree care and planting and care of fruit trees in 1992 was $514,466,796 (table 1).

Homeowners also purchase professional tree-related services from companies that are classified into Standard Industrial Classification (SIC) Industry Group No. 078, which is the same as Sector 27 in the IMPLAN database. SIC 078 is composed of companies primarily engaged in one of these three industries: landscape planning and landscape architectural and counseling services (SIC 0781); lawn and garden services (SIC 0782); and ornamental shrub and tree services (SIC 0783). In 1992, California homeowners paid an estimated $44,668,923 to SIC 078 companies that submitted employment and payroll reports to appropriate government agencies. Services by these companies included planning and designing landscapes with trees, small amounts of tree planting, trimming, pruning, spraying, removal, surgery and other arborist services.

In short, in 1992 California households spent an estimated $559,135,720 for do-it-yourself activities related to trees and for some types of contractual work attributable to trees in residential landscapes (table 1).

City and county government

City and county governments spent an estimated $110,062,088 and $7,100,537 respectively for urban forestry programs in 1992 or 1991-1992. These estimates are based on the amount of expenditures reported by some city and county governments in response to a recent survey sponsored by the California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection (CDF), the expenditures of two other cities that provided the information, and our estimates of the expenditures of nonrespondents. In general, our estimate of a nonrespondent's expenditure on community forestry equals the probability that the city or county in a particular population group spent money on urban forestry activities times the expenditure per capita of the city or county respondents in that group times the population of the non-responding city or county. The $7,100,537 figure also includes an estimated $164,629 of financial support from county governments for UC Cooperative Extension's urban tree-related research and educational services (table 1).

State government

Various departments, commissions and institutions of state government either manage state-owned landscapes with trees or provide grants for urban forestry tree planting, research and education. Based on data from the Division of Maintenance and the Office of Landscape Architecture in the California Department of Transportation, we estimate that CalTrans spent $9,405,024 in 1992–1993 for pruning, trimming, removing, replacing, fertilizing and mulching existing trees, controlling tree pests, cleaning up fallen trees and tree vegetation, planting new trees and creating landscape designs that include trees.

The Resources Agency and the California Transportation Commission (CTC) provide grants from Proposition 111 bonds to various state agencies, local governments and nongovernmental organizations to mitigate environmental damage caused by transportation projects. CTC approves three kinds of grants: highway landscape and urban forestry, roadside recreation and resource lands. Grants usually contain funds for tree-related activities, primarily maintenance and planting. The state government spent an estimated $4,159,022 of Proposition 111 funds for these activities in fiscal year (FY) 1991–1992.

The CDF spent $826,608 in FY 1992–1993 for tree planting, education, research and other urban forestry programs. Proposition 70 is the largest source of money that CDF spends. General revenues account for the remainder. In 1992–1993 the state government, through UC, paid approximately $493,887 to Cooperative Extension for community tree-related research and educational services and about $127,500 to UC's Experiment Stations for urban forestry research.

Altogether, these departments and agencies of the state government spent a total of $15,012,041 on tree maintenance, planting, education and research (table 1). However, these expenditures do not include those made by state and local government enterprises.

State, local enterprises

This category refers to local government passenger transit (IMPLAN Sector 510) and other state and local government enterprises (IMPLAN Sector 512). Sector 512 includes airports, liquor stores, housing and community development agencies, and utilities that provide sanitation, sewage treatment, water and gas. These state and local government enterprises spent an estimated $4,240,387 in 1992 for tree-related contractual services from landscape planners and horticultural and arboricultural companies (table 1).

Federal government

The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) is the largest single federal buyer of urban forestry products and services in the state. The USDA paid approximately $127,500 to UC's Experiment Stations and $164,629 to Cooperative Extension for urban forestry in the state. The Forest Service of the USDA provided $253,400 in National Urban Forestry (NUF) grants administered by California ReLeaf to various community tree groups, primarily to promote volunteer participation in these groups. The Forest Service also provided $391,908 in NUF funds to the CDF. In total, the USDA spent $937,437 on urban forestry in California in 1992–1993.

Federal government institutions in California also purchase tree-related services from landscape planning (SIC 0781), lawn and garden service (0782) and ornamental shrub and tree service (0783) companies primarily for the purpose of caring for trees on federal government landscapes. The relevant institutions make up four different federal sectors in the IMPLAN database: Sector 513, the U.S. Postal Service; Sector 515, other federal government enterprises, including national airports, military PXs, Federal Home Lean Bank, Pension Guarantee Fund and the Overseas Investment Company; the Department of Defense; and all nonmilitary institutions of the federal government in the state. In 1992 these sectors purchased an estimated $1,532,127 of tree-related contractual services from SIC 078 companies.

In total, these federal government institutions and the USDA together spent $2,469,563 for California urban forests and related activities in 1992 (table 1).

All government

Various agencies, departments, commissions and other institutions of government at the local, state and federal levels spent an estimated $138,884,616 for tree maintenance, planting, research, education and landscape planning in 1992. The spending decreases as the government's authority becomes more removed or the jurisdiction more encompassing. That is, local government spends more on urban forestry than state government, which spends more than the federal government (table 1).

Electric utilities

Electric utilities spend more money on tree-related activities than any business spends. The delivery of their product, electricity, depends on power lines that are unfettered by trees. Thus their largest urban-forestry expenditure is for utility line clearance, which involves a special kind of tree trimming and, on occasion, tree removal. The five largest electric utilities in the state — Pacific Gas and Electric (PG&E), Southern California Edison (SCE), Los Angeles Department of Water and Power (LADWP), San Diego Gas and Electric (SDG&E) and Sacramento Municipal Utility District (SMUD) — reported expenditures of $77,090,385 for line clearance in 1992. Four of these utilities also incurred an estimated $32,238,010 in expenses for tree-related outages, tree trimming, tree planting, tree-related legal expenses and urban forestry research. Thus the five largest utilities had expenses of at least $109,328,395 for line clearance and other tree-related activities in 1992.

In addition to LADWP and SMUD, there are 29 other consumer-owned, or municipal, electric utilities and 4 rural electric companies, according to the 1991 California Almanac. These other utilities had about 899,756 customers throughout the state. PG&E, SCE, LADWP and SMUD had tree-related expenses per customer in 1992 of about $10.17. Using the tree-related expenses per customer of these four utilities as the best available estimate of the tree-related expenses per customer of the 33 other municipal and rural electric utilities, we estimate that these other utilities had urban-forestry expenses of $9,148,643. Thus electric utilities had expenses of $118,477,038 in 1992 for line clearance and other tree-related activities (table 1).

Public and private schools

Educational institutions of local and state governments and private schools spend money on tree care, tree planting and other tree-related services. While some schools perform these services themselves, we believe that many schools hire others, including horticultural and arboricultural companies. Thus sales of products and services of companies in SIC 078 to schools are likely to contain the expenditures of most schools for tree care. California's public and private schools spent an estimated $10,946,707 for contractual maintenance, tree-related landscape planning and some tree planting from private landscape counseling, lawn and garden-service and shrub and tree-care companies in 1992 (table 1).

Community tree groups spend their income to plant trees and to conduct educational programs on the importance of trees and their care.

Community tree groups

Community tree groups exist throughout California and play an important role in promoting tree planting and awareness about the importance of urban forests and their care in the state. Nonprofit and local volunteer tree groups spend their income to plant trees, conduct educational programs on the importance of trees and their care and perform other urban forestry services in the state. In cooperation with California ReLeaf, we surveyed about 40 community tree groups about their recent annual expenditures. The 14 respondents included the 5 largest community tree groups in the state — Tree People in Los Angeles, the Sacramento Tree Foundation, Friends of the Urban Forest in San Francisco, Tree Fresno and California Oak Foundation in Oakland — and most of the groups with any substantial budgets. The total annual expenditure of these 14 groups in 1992, 1993 or 1992-1993 was $4,401,831. However, $1,859,721 of the money spent came from National Urban Forestry (NUF) grants, California Department of Forestry grants, Proposition 70 and 111 grants and electric utilities. Therefore community tree groups spent $2,542,110 that has not been counted elsewhere (table 1).

Other buyers in California

Real estate companies, hotels and lodging places, amusement and recreation service companies, nursing and health-care facilities, religious organizations and many other businesses and organizations in California spend money on tree care and other tree-related services. In 1992 these other buyers spent an estimated $110,279,446 on tree-related services from landscape architectural, horticultural and arboricultural companies (table 1).

Other expenditures

A number of important urban forestry expenditures have not been yet been counted. For example, in 1992–93 citizens of San Jose and their government spent about $7,091,820, or $8.80 per capita, for the following community tree-related activities: repair of sidewalks damaged by trees; repair of sewers and storm drains damaged by trees; clearing storm inlet drains clogged with tree leaves; disposal of tree waste; and legal services and liability claims for injuries caused by public trees.

San Jose has a well-developed urban forest and related management program. Nevertheless, this information from San Jose, which had a population of 806,200 in 1992, suggests the importance of expenditures for these urban forestry activities in the rest of the state, which had a population of 30,175,800 in the same year. Under the assumption that the per capita expenditure in the rest of the state is half of the per capita amount in San Jose, residents and local governments in other cities and unincorporated areas of the state spent about $132,721,824 for these five urban forestry activities. Thus total expenditure in 1992–1993 for these tree-related repairs, disposal costs, legal fees and liability claims was $139,813,644 (table 1).

U.S. buyers outside of California

Private companies that sell landscape design, horticultural and arboricultural services in California also sell them outside the state. Buyers in other states purchased an estimated $168,366,485 worth of tree-related services from these California companies in 1992 (table 1).

Economic impacts

In total, we estimate $1,248 billion ($1,248,445,765) of expenditures per year, based on data from the early 1990s, for California-related urban-forestry products and services. With the possible exception of some household purchases from out-of-state sellers, this amount also represents urban forestry sales of sellers located in the state. These urban forestry sales create ripple effects on sales, employment and personal income in the state's economy. Ripple effects occur because urban forestry sellers buy intermediate products from other industries and because households, the primary income recipients in the economy, spend some of their additional income on more goods and services.

As a result, the total impact of urban forestry on sales in the state is an estimated $3,789 billion. In turn, this $3,789 billion in total sales translates into $2.092. billion of income to individuals in the state. We also estimate that 64,062 jobs are supported throughout the California economy as a result of the $1.248 billion in sales of urban-forest related products and services and its ripple effects. If buyers had spent this $1.248 billion outside of California, total sales in the state would have been about $3,789 billion less, the income of individuals in the state would have been lower by $2.092 billion, and there would have been about 64,062 fewer jobs.

Caveats and conclusions

To put $1.248 billion into perspective, the state's commercial forest products industry had sales of $12.557 billion and the agricultural sector had sales of $18.858 billion in 1992. However, the estimates of $1.248 billion and the related impacts on total sales, income and employment are conservative lower bounds. For a more comprehensive and larger estimate of the economic impacts of urban forestry, financial support is needed for researchers to estimate expenditures on the following important urban forest activities.

First, homeowners and other property owners spend money on equipment and contractors to clear and repair sewer lines that run from houses and other buildings to the main sewer lines and that are clogged with leaves or damaged by tree roots. Second, property owners pay plumbers and local water utilities to repair water lines that are damaged by tree roots. Third, government institutions, particularly those at the local level, spend money to repair curbs and gutters that have been damaged by tree roots. Fourth, individuals and businesses pay legal fees and liability claims for injuries, disabilities and deaths that are attributable to trees. Fifth, in addition to injuries, individuals pay medical bills for tree-related allergies.

Sixth, households and businesses spend money on tree relocation and preservation. However, most of these sales are not included in the sector 27 sales, because most tree relocation and preservation is performed either by specialists called tree spaders or tree boxers or by large nurseries, neither of which belongs to SIC 078.

Seventh, landscape contractors are paid to plant trees and install landscapes with trees. Although our estimates of the expenditures of utilities, community tree groups and government institutions other than government enterprises include any purchases of tree planting and tree-related landscape installation by landscape contractors, our other estimates do not.

Eighth, government enterprises, schools, “other buyers in California” and buyers in other states purchase trees from nurseries and growers when they plant trees or install landscapes with trees themselves. Our estimates of the urban forestry expenditures of these buyers do not include such purchases. However, our estimates of the expenditures of households, government institutions other than government enterprises, utilities and community tree groups do include their purchases of trees and other tree planting inputs from nurseries and growers.

Ninth, certain professional associations spend money on training, certification, research and lobbying to promote the interests of their members, some or all of whom reside in California and grow nursery trees, design and install landscapes with trees or provide various arborist services. Examples of these associations are the California Association of Nurserymen, the California Landscape Contractors Association, the California and American Association of Landscape Architects, the American Society of Consulting Arborists, the Council of Tree and Landscape Appraisers and the Western Chapter of the International Society of Arboriculture.

We would not be surprised if the $1.248 billion estimate of urban-forestry sales by California businesses increased by as much as 100% if these additional nine types of expenditure were estimated and included in future research.

The figure of $1,248,445,765 less the $168,366,485 of expenditures by buyers in other states equals $1,080,079,280 and represents expenditures by California residents on urban forests in the state. These expenditures exemplify the annual costs that state residents incur to have and use these natural resources. In general, knowledge of these expenditures on urban forests is necessary for efficient and equitable management of these resources. In particular, comprehensive estimation of these expenditures is critical for voters and government officials who have to make decisions that affect the allocation of water and tax revenue in the state.