All Issues

Sidebar: San Diego farmers put ‘sustainability’ into practice

Publication Information

California Agriculture 47(2):11-12.

Published March 01, 1993

PDF | Citation | Permissions

Abstract

Abstract Not Available – First paragraph follows: The most conspicuous characteristic of agriculture in San Diego's coastal north is not the farms. It is urban encroachment. Housing developments. Golf courses. Shopping centers.

Full text

Housing developments and other forms of urban encroachment have replaced much of San Diego County's former farmland.

The most conspicuous characteristic of agriculture in San Diego's coastal north is not the farms. It is urban encroachment. Housing developments. Golf courses. Shopping centers.

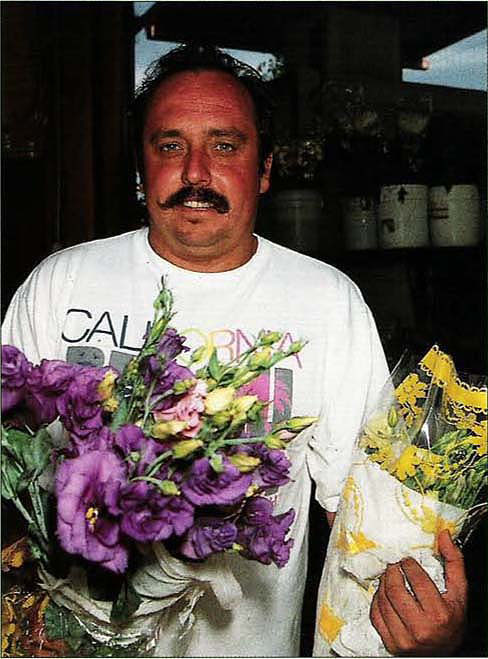

Scattered in isolated pockets, however, is a surprising number of farms, such as Richard Borevitz's Gourmet Gardens. His family runs a 20-acre specialty vegetable operation and irrigation supply business in San Marcos. All produce is marketed directly through a farm stand, local restaurants and stores.

“They demand and generally get top prices due to the wide variety and high quality produce they offer their customers,” says San Diego County Farm Advisor Faustino Muñoz, who has worked extensively with Borevitz.

Borevitz and Muñoz regularly experiment with technologies on a small plot on the farm. One project demonstrated to farmers how they could save water and energy by planting a legume green manure crop of Lana woolypod vetch. At a field day last August, local farmers learned about solarization as a nonchemical method of weed control.

The field day on solarization exemplifies a theme that runs through all of Muñoz's work — sustainable agriculture. The days of synthetic agricultural chemicals like methyl bromide are numbered, Muñoz believes. “Sustainable is defined as staying in business,” he says, “and in the 1990s they (small farmers) will have to learn how to farm without chemicals to stay in business.”

Muñoz is apparently getting his message across. As of October 1992, San Diego County had 170 registered organic farmers — the highest number of any county in the state but still a tiny percentage of the county's estimated 3,000 small farms.

Muñoz, who worked as a youth on his family's Imperial Valley farm, has been cultivating his interest in organic production techniques since 1984, when he surveyed farmers to get a better idea of the crops they were raising, the size of their operations and their research needs.

Many farmers wanted to learn about organic farming, so in 1986 Muñoz embarked on sabbatic to study sustainable agriculture at the Alchemy Center in Massachusetts and the Rodale Institute in Pennsylvania. “We didn't have many resources to draw from,” Muñoz says. “Most of the information came from outside the land grant system at that time.”

His program has since grown to include seminars, conferences, research projects and publications on sustainable agriculture. Muñoz has also extended information to Spanish-speaking small farmers in special workshops. His educational efforts earned him the 1991 American Farmland Trust agricultural conservation award for localized public education.

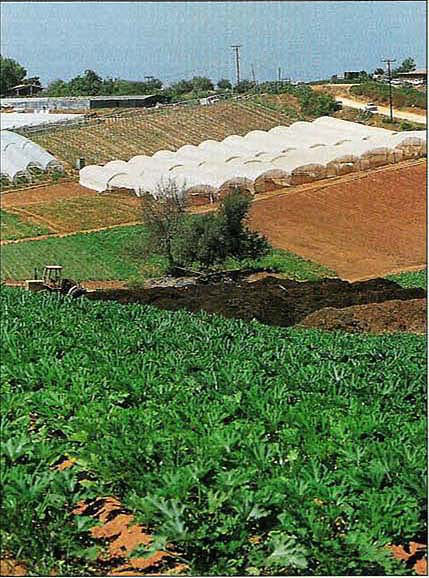

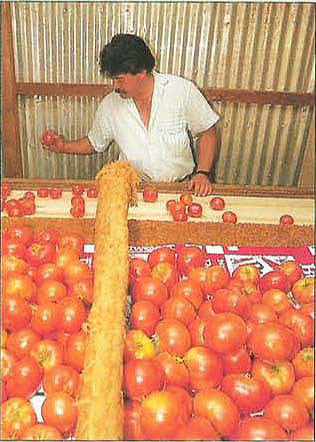

Escondido grower Joe Rodriguez who with his brother Carlos owns and operates JR Organics. The brothers emphasize fresh cut flowers and organic vegetable production.

In addition to their on-site insectary, the Rodriguezes employ cover crops and composted chicken manure (middle of picture) for fertilizer. Greenhouses are used to grow organic tomatoes early in the season.

Muñoz is now developing a project to foster a socially, environmentally and economically sustainable niche for San Diego County's small farms. Working with Borevitz, other farmers and local community leaders, Muñoz wants to build a center where farmers can learn new techniques, consumers can buy locally grown produce, and schoolchildren can learn about where food comes from.

The guiding principle behind the project is a cooperative approach in which “members” invest time and/or money in exchange for farm-fresh food and smallscale farmers are guaranteed a reliable local market. It is called community-supported agriculture (CSA), and its proponents describe it as “a form of cooperation between farmers and consumers who come together to produce healthy food in a sustainable way.”

Muñoz has applied for a grant from the Kellogg Foundation to begin the project. Once established, an advisory committee of small farmers, farm workers, consumers, community leaders, government agencies and Extension staff would steer such project activities as:

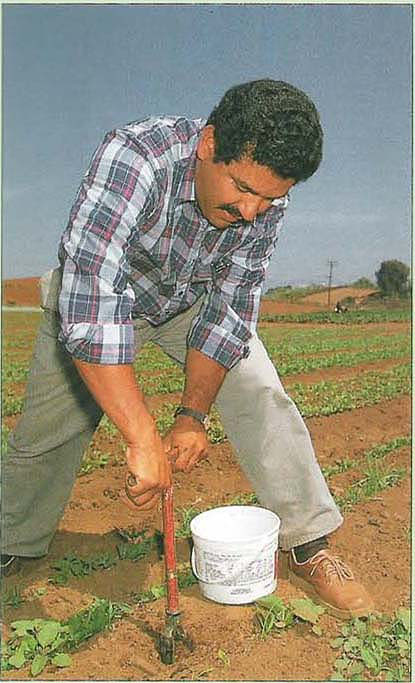

San Diego County Farm Advisor Faustino Muñoz takes a soil sample from the JR Organics farm for a laboratory analysis. Recent seed germination problems may be linked to salt buildup from composted chicken manure; Muñoz has encouraged legume cultivation to diversify the farm's soil fertility program.

A business plan and feasibility study for the regional produce market, farm demonstration site and agricultural science center.

-

Educational programs for migrant farm workers and their families in nutrition, youth development, leadership training and pesticide safety.

-

A farm worker organic garden with accompanying short courses and field demonstrations.

-

Establishment of a direct marketing connection between an organic farm and an adjacent senior citizen community.

-

Field demonstrations and seminars on sustainable and organic agricultural practices.

In the long term, Muñoz hopes, the project will result in a plan that protects the environment, provides high-quality local produce and supports the economic viability of small family farmers. The San Diego project reflects the progress made by proponents of sustainable agriculture.

“I like to think we've helped to take the myth out of it,” Muñoz says. “Sustainable agriculture is no longer viewed as extremist. It's a more legitimate, acceptable and worthwhile goal. The program has also helped UC to define its role in sustainable agriculture in the state and nationally.”