All Issues

Asian citrus psyllid and huanglongbing disease threaten California citrus

Publication Information

California Agriculture 66(4):127-130.

Published online October 01, 2012

PDF | Citation | Permissions

Full text

Asian citrus psyllid is slowly spreading in California, and huanglongbing disease (also known as citrus greening) will likely become established in the state, requiring citrus farmers and residents with citrus in their landscapes to become accustomed to a new reality.

“Asian citrus psyllid and huanglongbing disease have played out this way around the world, including in Florida, Texas and other states,” said UC Cooperative Extension specialist Beth Grafton-Cardwell. “There is no reason to believe California will be immune to the natural progression of this disease complex.”

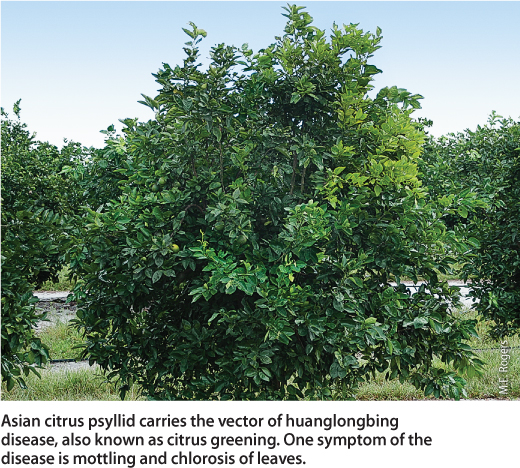

Asian citrus psyllid carries the vector of huanglongbing disease, also known as citrus greening. One symptom of the disease is mottling and chlorosis of leaves.

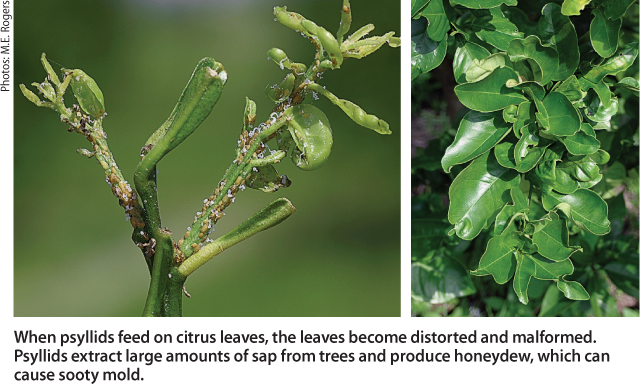

The aphid-sized Asian citrus psyllid was first identified in California in 2008 and is currently found in Imperial, San Diego, Los Angeles, Orange, Riverside, and San Bernardino counties. Asian citrus psyllid injects a toxin when it feeds on citrus leaves or stems, causing shoot deformation and plant stunting. Of greater concern is the fact that it vectors the bacterium associated with huanglongbing disease. Every tree infected with the pathogen will suffer a premature death, sometimes in as little as 3 years.

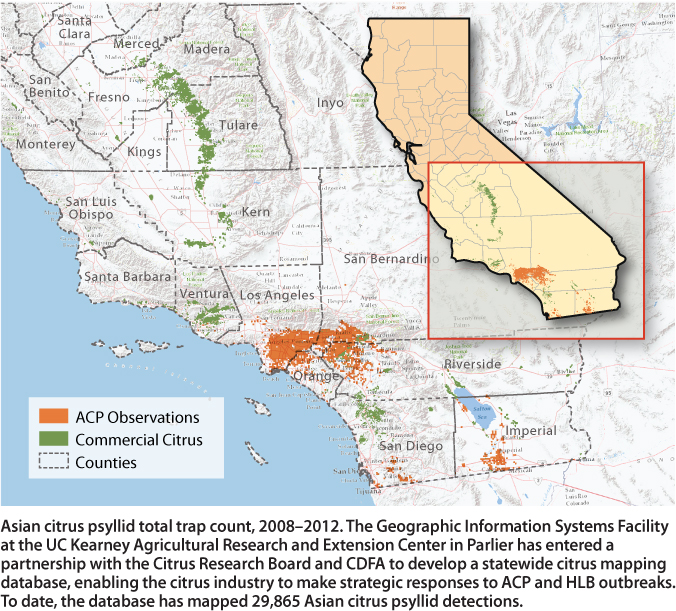

Asian citrus psyllid total trap count, 2008–2012. The Geographic Information Systems Facility at the UC Kearney Agricultural Research and Extension Center in Parlier has entered a partnership with the Citrus Research Board and CDFA to develop a statewide citrus mapping database, enabling the citrus industry to make strategic responses to ACP and HLB outbreaks. To date, the database has mapped 29,865 Asian citrus psyllid detections.

But that doesn't mean UC researchers and UC Cooperative Extension specialists and advisors are giving this serious citrus disease free rein in the Golden State. UC is working with officials from the citrus industry, U.S. Department of Agriculture and California Department of Food and Agriculture (CDFA) to wage an all-out battle.

They aim to contain psyllid populations, catch the infection early in order to rapidly remove infected trees, and monitor commercial citrus using geospatial technology. Meanwhile, scientists in university laboratories are exploring the trees, the pest and the pathogen at the molecular and genetic levels to find a long-term cure, while advisors are engaging and educating the public to help in the fight against the disease's spread.

Spread of the psyllid

In March 2012, huanglongbing disease was detected in California for the first time. The multigrafted citrus tree in a Los Angeles County backyard was destroyed, but it is likely there are more infected trees nearby or in other areas. The disease is also spreading northward in Mexico toward California.

The psyllid and disease together present a grave threat to California's $2.1 billion citrus industry, the livelihood of citrus farmers and thousands of farmworkers, and the fragile economies in California's rural citrus belt, extending from San Diego through interior and coastal Southern California and up into the San Joaquin Valley. Their presence prevents exports to countries that do not have this pest and disease. The loss of citrus trees in urban areas of California due to the disease will change the face of the landscape and reduce the availability of local fruit.

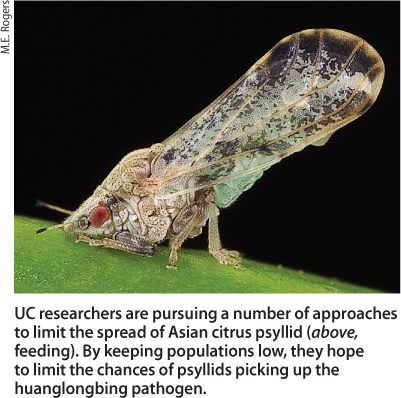

UC researchers are pursuing a number of approaches to limit the spread of Asian citrus psyllid (above, feeding). By keeping populations low, they hope to limit the chances of psyllids picking up the huanglongbing pathogen.

When psyllids feed on citrus leaves, the leaves become distorted and malformed. Psyllids extract large amounts of sap from trees and produce honeydew, which can cause sooty mold.

Ensuring pathogen-tested plant material

The state of California has strict regulations in place to ensure that citrus trees are produced with pathogen-tested propagative material. However, the general public does not always understand the importance of these regulations, and people sometimes unknowingly bring diseased plant material into California and graft their own trees. The UC Citrus Clonal Protection Program (CCPP), housed at UC Riverside, is the gatekeeper of California citrus. Directed by Georgios Vidalakis, UCCE specialist in the Department of Plant Pathology at UC Riverside, CCPP is one of three programs authorized nationwide to import citrus bud-wood from overseas. CCPP services include disease diagnosis, pathogen detection and elimination, and the distribution of true-to-type citrus propagative material of fruit and rootstock varieties to nurseries and private individuals.

In the face of the current citrus threat, scientists at UC Riverside are developing a legal source of plant material for popular noncitrus hosts of the psyllid, such as bael tree, a native food plant of India also used for traditional medicine, and Indian curry leaf, a flavoring common in the cuisine of India, Pakistan, Bangladesh and other Southeast Asian countries. The program — run by Tracy Kahn, principal museum scientist, and David Karp, associate in the Agricultural Experiment Station, in the UC Riverside Department of Botany and Plant Sciences — will provide clients with pathogen-tested plants, reducing the incentive for smuggling plants and plant material into California that potentially harbor Asian citrus psyllid or huanglongbing disease.

Managing the psyllid

Asian citrus psyllid is currently found only in Southern California. The majority of commercial citrus is grown in Central California. If its spread northward can be slowed, it minimizes quarantine and export issues and reduces the threat to Central Valley citrus production. If psyllid populations are kept low wherever they are found, then their chances of picking up the huanglongbing pathogen are reduced and spread of the disease is slowed. UC is actively mapping, monitoring and finding the best way to treat Asian citrus psyllid to keep the Southern California populations in check.

Frank Byrne, an associate research entomologist, and Joe Morse, a professor in the Department of Entomology at UC Riverside, are studying the efficacy of the systemic pesticide imidacloprid to protect citrus trees in nurseries. “The treatments can protect the young trees for up to 3 months,” Byrne said.

Scientists with UC Cooperative Extension are developing treatment options for homeowners and farmers who do not use synthetic pesticides on their citrus. The current recommendation for organic growers is to spray a low rate of horticultural spray oil on trees at 14-day intervals. Grafton-Cardwell is evaluating the effect of this treatment on citrus health, productivity and fruit quality for San Joaquin Valley navel oranges. Jim Bethke, UCCE advisor in San Diego County, is screening additional organic insecticides on a greenhouse colony of Asian citrus psyllid to find products that may have greater persistence and efficacy.

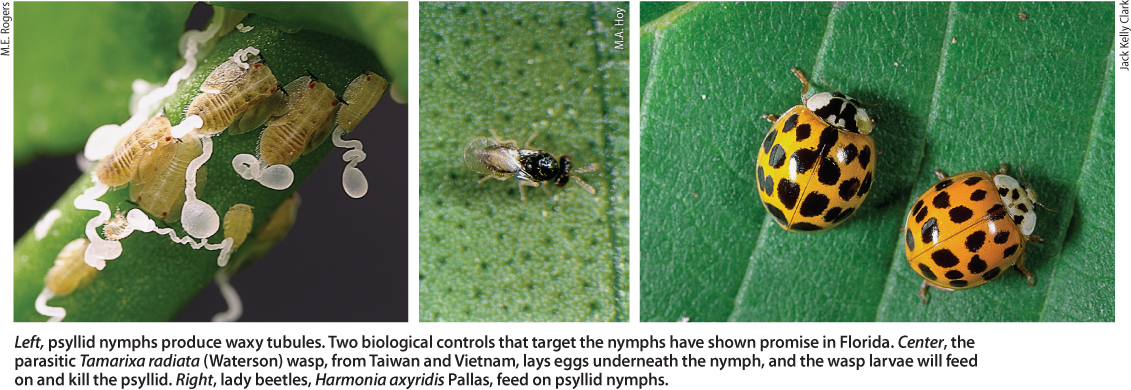

Mark Hoddle, UCCE specialist in the Department of Entomology at UC Riverside, collected two natural enemies of Asian citrus psyllid in Pakistan. The first is a tiny wasp, Tamarixia radiata, which lays eggs underneath late-stage nymphs. The hatching larvae eat the nymphs, killing them. The other, Diaphorencyrtus aligarhensis, is a small wasp that lays eggs in younger psyllid nymphs. Tamarixia is being released in urban areas of Southern California to help reduce Asian citrus psyllid populations.

Left, psyllid nymphs produce waxy tubules. Two biological controls that target the nymphs have shown promise in Florida. Center, the parasitic Tamarixa radiata (Waterson) wasp, from Taiwan and Vietnam, lays eggs underneath the nymph, and the wasp larvae will feed on and kill the psyllid. Right, lady beetles, Harmonia axyridis Pallas, feed on psyllid nymphs.

At the UC Kearney Agricultural Research and Extension Center in Parlier, a geospatial map is being developed by the geographical information systems (GIS) team, led by Kris Lynn-Patterson, academic coordinator. The citrus map will be enriched with details about the California citrus groves — types of trees, whether conventional or organic, ownership, management and who is packing the fruit. Another layer on the database will identify factors that could influence the direction and speed of Asian citrus psyllid spread after an infestation is detected, such as weather patterns and traffic corridors.

Detecting infected trees

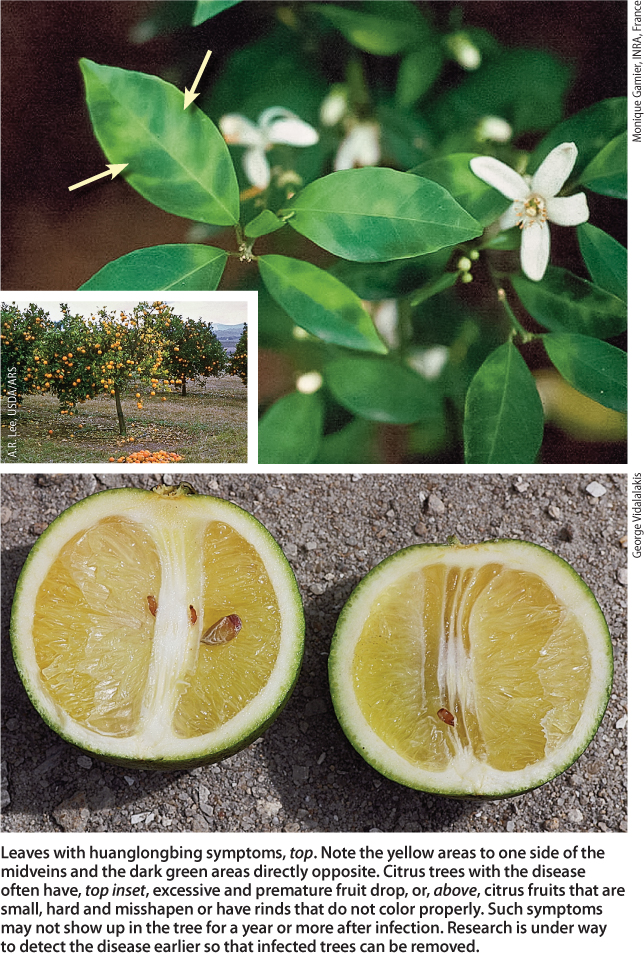

Finding trees infected with huanglongbing disease and eliminating them before the Asian citrus psyllid picks up the pathogen and spreads it to neighboring trees is a major challenge. The pathogen in the tree cannot be detected by lab testing for several months, and the symptoms — yellowed leaves, small and bitter fruit — may not show up for a year or more after infection. Meanwhile, the disease can be spread by the psyllid. Research is under way to develop early disease detection so that infected trees can be rapidly removed.

Cristina Davis, professor in the UC Davis Department of Mechanical and Aerospace Engineering, and Abhaya Dandekar, professor in the UC Davis Department of Plant Sciences, are refining a mobile chemical sensor that can rapidly discriminate between healthy and diseased citrus trees by sniffing their volatile organic compounds (VOCs). The researchers collected samples of VOCs emitted from trees infected with huanglongbing disease in Florida every month for a year in order to train the mobile sensor to recognize its smell. “The idea is to extract a group of compounds that creates the signature for the presence of huanglongbing disease,” Dandekar said. A software program develops an algorithm that lets the machine know it is detecting the disease.

Leaves with huanglongbing symptoms, top. Note the yellow areas to one side of the midveins and the dark green areas directly opposite. Citrus trees with the disease often have, top inset, excessive and premature fruit drop, or, above, citrus fruits that are small, hard and misshapen or have rinds that do not color properly. Such symptoms may not show up in the tree for a year or more after infection. Research is under way to detect the disease earlier so that infected trees can be removed.

Carolyn Slupsky, UC Davis assistant professor with a split appointment in the Department of Nutrition and Department of Food Science and Technology, is looking at the metabolism of citrus trees infected with the pathogen associated with huanglongbing disease. Hailing Jin, associate professor in the Department of Plant Pathology and Microbiology at UC Riverside, is working to identify the huanglongbing-induced small RNAs that will indicate whether a citrus tree is infected with the disease. Wenbo Ma, associate professor of plant pathology at UC Riverside, believes pathogen-specific proteins in the tree's phloem, the food-conducting tissues of the plant, could be used as a more reliable disease detection tool than the pathogen itself.

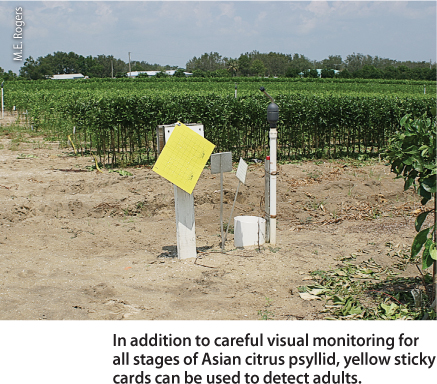

In addition to careful visual monitoring for all stages of Asian citrus psyllid, yellow sticky cards can be used to detect adults.

Finding long-term solutions

Managing psyllids with insecticides and biological control doesn't eliminate the entire pest population, and it is difficult to remove infected trees fast enough to stay ahead of the disease's spread. Long-term solutions are needed to develop a citrus tree that can resist or withstand the bacterium and produce good-tasting, abundant fruit, or confound the psyllid so that it cannot transmit the disease.

Dandekar and his colleagues are experimenting with gene fusion to make citrus plants more effective at fighting the disease. “Many disease-causing microbes can evade one defensive action by a host plant, but we believe that most microbes would have difficulty overcoming a combination of two immune-system defenses,” Dandekar said.

In Florida, researchers have found that trifoliate orange rootstock has some natural resistance to huanglongbing disease. They have enlisted their long-time collaborators in California to help determine the mechanism of this partial resistance and, eventually, to transfer it to edible citrus varieties. Mikeal Roose, professor in the Department of Botany and Plant Sciences at UC Riverside, and his colleagues are assisting in the genetic analysis of about 200 hybrid crosses between sweet orange and trifoliate orange, a species used as a rootstock. “We are sequencing a large number of genome fragments to find particular fragments that are associated with resistance,” Roose said.

Engaging and educating the public

The ability to keep Asian citrus psyllid and huanglongbing disease at bay depends in large part on the active involvement of commercial citrus growers and California residents with citrus trees in their home landscapes. They need to understand the impact of the disease on their trees and participate in the management program. Grafton-Cardwell has pulled together a team of scientists to develop large-scale extension activities and aggressive management programs to stave off devastating commercial and residential losses in California. The project is funded with a 5-year grant from UC Agriculture and Natural Resources.

A team of USDA and UC scientists are producing a palm-sized flipbook that will give CDFA inspectors ready access to pictures and the identifying features of 25 plants that are hosts of Asian citrus psyllid. The California Citrus Research Board, which is funding much of the current university research, will publish the flipbook. Matt Daugherty, UCCE specialist in the Department of Entomology at UC Riverside, will be researching the plant management practices used in retail nurseries and garden centers, such as irrigation frequency, soil type and pot size. Pam Giesel, UCCE academic coordinator for the UC Master Gardener program, is working with Daugherty on a statewide effort to engage UCCE's 5,500 volunteer master gardeners in an education program. Scientists will train master gardeners and provide curriculum and other learning materials so they can convey information about the pest and its management to residents they serve.

Karen Jetter, associate project economist with the UC Agricultural Issues Center in Davis, is developing economic models to estimate the costs of Asian citrus psyllid and management in backyard citrus and commercial orchards, and linking the information to a geospatial database. “The tool will include all the information necessary for a homeowner, grower or pest control adviser to determine the most effective and affordable pest management for his or her situation,” Jetter said.

Sustainable citrus production in California in the presence of Asian citrus psyllid and huanglongbing disease will depend upon a combination of tactics, including genetic engineering as well as applied pest and disease management strategies, Grafton-Cardwell said.

“Scientists at UC and around the world are working to develop solutions,” she said.