All Issues

Southeast Asian refugees learn modern farming methods

Publication Information

California Agriculture 47(2):9-9.

Published March 01, 1993

PDF | Citation | Permissions

Full text

Looking up from a newly picked row of Japanese eggplant, Chan Eagle greeted Pedro Ilic in English difficult to understand but with gestures expressing gratitude at the sight of the Fresno County farm advisor.

“She came into my office several years ago in tears,” Ilic explained. “She'd never farmed before and was trying unsuccessfully to grow on this clay soil on the west side of town.”

Twenty years ago she had met and married a soldier who moved her from her native Laos to Arkansas. When she moved to Fresno and suffered a failure in farming, Ilic advised her to start over on a different patch of Fresno County with vegetable production techniques he had developed for other small-scale growers, enabling them to raise their crops more efficiently and profitably. Those techniques included fumigation, drip irrigation and use of plastic row covers.

His advice paid off. Last summer, when some of her neighbors were harvesting 10 boxes of eggplant per acre, Chan Eagle was producing 100. Furthermore, she is considered a shrewd negotiator by local produce buyers of the eggplant — and Oriental herbs — she raises by herself.

Traditionally, Fresno County's smallscale farmers were Japanese, Filipino, Hindu and Sikh, as well as African-American and Anglo, and they produced cherry tomatoes, strawberries, cucurbits, Chinese long beans, eggplant, luffa and sugar peas. Then, in the early 1980s, 50,000 Southeast Asian refugees — Hmong, Thai, Laotians, Vietnamese and Cambodians — settled in the San Joaquin Valley (and in other parts of California). On small parcels scattered around Fresno, these immigrants - alone or with several families - began growing lemongrass, mokua, opo, bitter melon and bok choy for Asian immigrant and Asian-American markets. Of Fresno County's small farm population, Ilic estimates 800 refugees farm 3,000 acres.

These small farmers have contributed more than just new specialty vegetables to California. Southeast Asian farmers have improved the local economy, Ilic observes, by purchasing fertilizers, seeds, plastic, pesticides, backpack sprayers, tractors, rototillers, drip irrigation line, shovels, hoes, fittings and other farm equipment.

But the newcomers face formidable language and cultural barriers, limited access to good quality land and an agriculture vastly different from Southeast Asia's. Ilic occasionally enlists the aid of translators, when funds are available, to help these farmers thread through the maze of modern production techniques, marketing systems and regulatory restrictions. He finds some refugees reluctant to trust anyone from the government who offers help.

Farm Advisor Pedro Ilic discusses cultural techniques with Fresno farmer Chan Eagle, a Laotian immigrant who raises Oriental specialty crops.

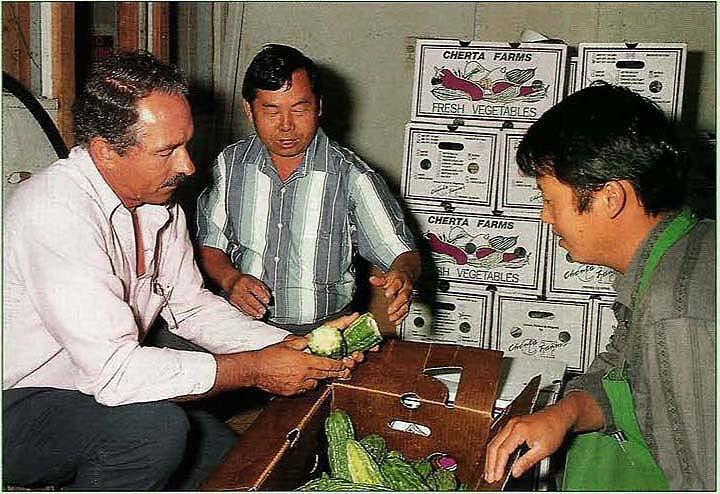

Ilic consults with Fresno County packer and wholesaler Leng C. Lee (middle), who is general manager of Cherta Farms. At right is helper Ge Vang. Lee works predominantly with Southeast Asian growers.

Ilic understands the difficulties of adapting to a new country. A student of agronomy in his native Chile, he came to California in the late 1960s on a Farm Bureau-sponsored scholarship to learn production techniques. He labored in San Joaquin Valley vineyards and orchards for a time, but he had other plans. “I came to stay in the United States because career opportunities in Chile were limited to people with connections,” he says. Subsequently, Ilic earned degrees at Fresno State in plant science and agricultural economics, with an emphasis on vegetable production.

“In this country opportunities abound,” he says, and the tools for success, technology and information, are today available to the many Southeast Asians who desire it. The challenge for Ilic — and for others working with them — is to penetrate the cultural and language barriers.

After working nearly 20 years in the Fresno area, Ilic believes Southeast Asians and other small-scale vegetable growers can be reached through a “Master Farmer” program, consisting of workshops, tours of successful farms and lectures from university experts. Its purpose is to teach trellis spacing, fertilizer management, crop selection, strip fumigation, pest control, cultural practices, marketing strategies and other scale-specific information growers need for success.

Ilic began this 1-year program in September 1992. Between 25 and 30 enrollees are expected to successfully complete the first course of 10 workshops.