All Issues

College students identify university support for basic needs and life skills as key ingredient in addressing food insecurity on campus

Publication Information

California Agriculture 71(3):130-138. https://doi.org/10.3733/ca.2017a0023

Published online September 13, 2017

PDF | Citation | Permissions

NALT Keywords

Abstract

A recent University of California (UC) systemwide survey showed that 42% of UC college students experience food insecurity, consistent with other studies among U.S. college students. As part of UC's efforts to understand and address student food insecurity, we conducted 11 focus group interviews across four student subpopulations at UC Los Angeles (n = 82). We explored student experiences, perceptions and concerns related to both food insecurity and food literacy, which may help protect students against food insecurity. Themes around food insecurity included student awareness about food insecurity, cost of university attendance, food insecurity consequences, and coping strategies. Themes around food literacy included existing knowledge and skills, enjoyment and social cohesion, and learning in the dining halls. Unifying themes included the campus food environment not meeting student needs, a desire for practical financial and food literacy “life skills” training, and skepticism about the university's commitment to adequately address student basic needs. The results of this study broadly suggest there is opportunity for the university to address student food insecurity through providing food literacy training, among other strategies.

Full text

Food insecurity, the uncertain or limited ability to get adequate food due to lack of financial resources, is a persistent problem in the United States. The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) estimated that 13% of U.S. households were food insecure in 2015 (Coleman-Jensen et al. 2016). Food insecurity is linked to several physical and mental health problems, such as poor self-reported health, poor diet quality, obesity, diabetes, depression and anxiety (Gundersen and Ziliak 2015; Seligman and Schillinger 2010).

Since the Great Recession in 2008, a rapidly growing number of U.S. studies have documented student food insecurity. Among college students, it is estimated that food insecurity ranges from 14% to 72% (Chaparro et al. 2009; Dubick et al. 2016; Freudenberg et al. 2011; Gaines et al. 2014; Goldrick-Rab et al. 2015; Hanna 2014; Maroto and Snelling 2015; Martinez et al. 2016; Morris et al. 2016; Patton-Lopez et al. 2014). Several recent studies showed that food-insecure students were more likely to self-report being in fair or poor health, experience depressive symptoms, and perform lower academically than food-secure peers (Freudenberg et al. 2011; Martinez et al. 2016; Patton-Lopez et al. 2014). The scale of food insecurity among students documented since the Great Recession suggests that it may be attributed to the rising cost of attendance (tuition and fees, books and supplies, housing and food, transportation, and personal expenses) and inadequate financial aid to meet basic needs, namely housing and food.

Fresh produce left over at the end of local farmers markets is collected — “gleaned” — by UCLA student volunteers in a partnership with Food Forward, a Los Angeles–based nonprofit organization that coordinates gleaning programs across the region. Here, the produce is distributed at no cost to graduate students and their families living at UCLA University Village.

A recent UC Student Food Access and Security Study reported that 42% of UC students have experienced food insecurity (Martinez et al. 2016). That study was funded by the UC Global Food Initiative (GFI), which had as one of its goals to identify and address food insecurity across the UC system. Also with support from the GFI, we undertook our qualitative research on student food insecurity to help contextualize the issue for UC. A secondary goal was to contribute to the GFI's understanding of food literacy among college students, and to help identify opportunities to advance food literacy across the UC system. Recently, food literacy has been conceptualized as a protective factor against both food insecurity and obesogenic environments (Cullerton et al. 2012, unpublished). Although the research is nascent, promoting food literacy among college students may be an appropriate strategy to help protect students from food insecurity.

Our study used qualitative research methods to (1) better understand how students perceive, experience and cope with food insecurity, and (2) explore opportunities to address food insecurity by improving food literacy among college students.

Food literacy

Food literacy can be understood through the four domains established by Vidgen and Gallegos (2014) — food planning and management, selection, preparation, and eating. These domains are contextual in nature; that is, diet quality depends not only on the individual but also on the environment in which the individual lives. Like the expanded view of health literacy, food literacy can be viewed broadly as a skill set, which individuals use to navigate their food environment to enhance their well-being (Massey et al. 2012; Palumbo 2016).

Focus groups

We conducted 11 focus group discussions between March and June 2016 with 82 students enrolled at University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA). Students were recruited to ensure representation from four subpopulations: residential undergraduates (living on campus with a meal plan), nonresidential undergraduates (living off campus), graduate/professional students, and students using free food resources (e.g., Community Programs Office [CPO] Food Closet).

The first three subpopulations were recruited via emails sent out by Residential Life staff and academic department administrators. To purposively sample students using free food resources (used as a proxy for food insecurity), we obtained referrals from food program leaders and included both undergraduate and graduate students. Interested students completed an online screener so we could select a diverse student sample based on the following characteristics: gender, race/ethnicity, international student status, major/department, and year in school.

Students were assigned to appropriate focus groups to maximize homogeneity among participants. We held three focus groups with residential undergraduates, three with nonresidential undergraduates, three with graduate/professional students, and two with students using free food resources. Participation was incentivized with dinner at the focus group location and a $30 honorarium paid via electronic transfer to students' university ID card at the conclusion of participation. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at UCLA.

The interview guide was informed primarily by the qualitative literature and by our practical research goals; it was reviewed by UCLA faculty and GFI leaders, including a student food insecurity expert. The script was pilot-tested with a group of eight UCLA students and modified to improve conversational flow.

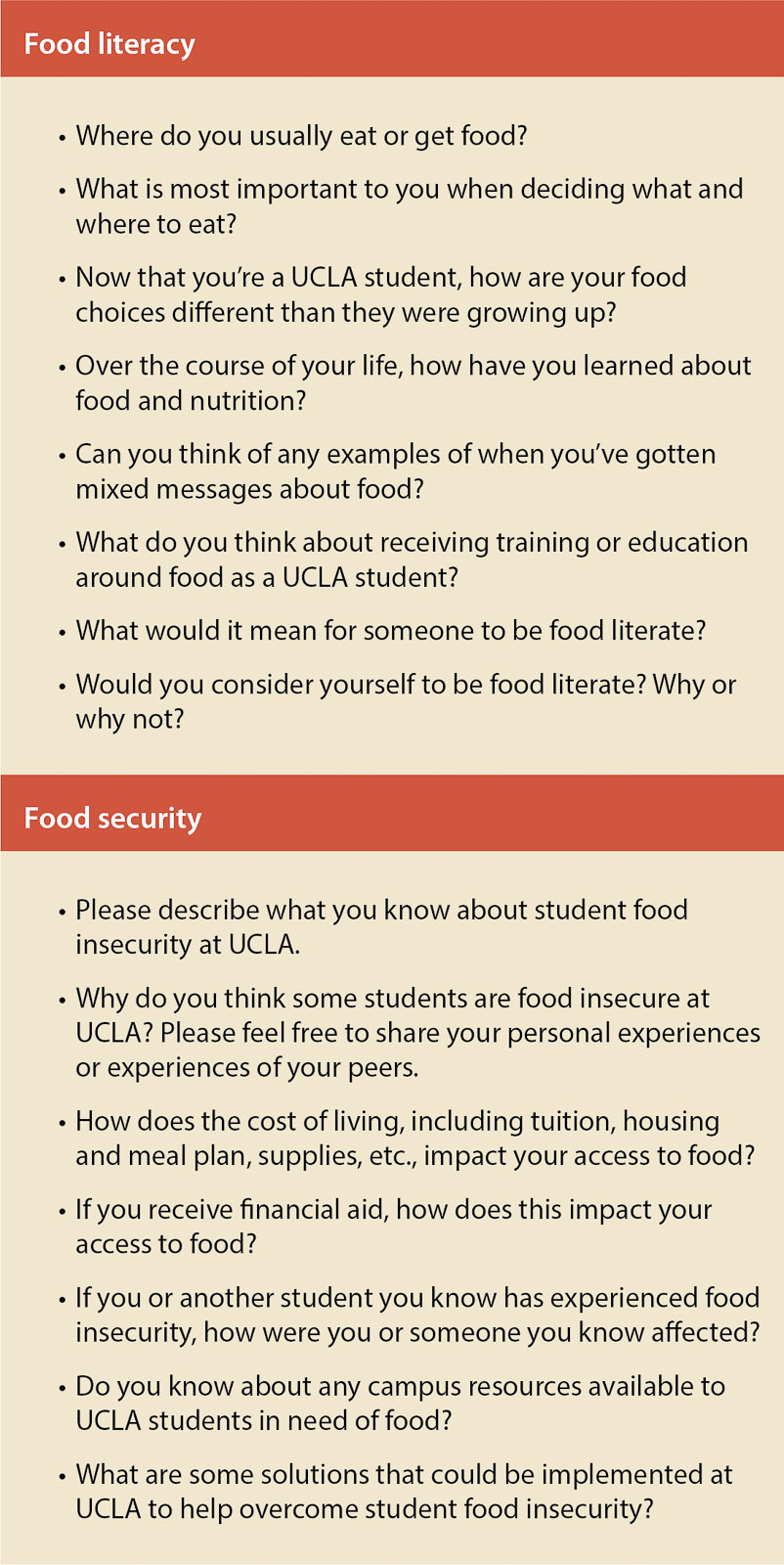

Focus group interviews were conducted in English, with five to 10 participants. Upon arrival, students were asked to read and sign informed-consent documents and complete a brief survey with demographic and food insecurity questions, including the USDA six-item food security short form survey module (USDA 2012). Focus group interviews were 90 minutes long and were facilitated by two authors (T.W. and H.M.). Facilitators used a semistructured interview guide, with the questions in the first half dedicated to food literacy and in the second half to food security (fig. 1). All discussions were audio-recorded.

Fig. 1. Focus group questions used to guide discussions with students about food literacy and food insecurity at UCLA.

Analytic strategy

We tabulated student characteristics for all 82 students. Food insecurity was assessed using the scoring criteria from the USDA six-item food security short form.

Each focus group audio recording was divided into two files, one consisting of the discussion on food literacy and the other of the discussion on food security. All audio files were transcribed verbatim by GMR Transcription Service. Two authors (T.W. and H.M.) employed an integrated approach using an inductive (ground-up) development of codes and themes and a deductive framework for organizing the codes according to the literature and interview guide. This involved an initial identification of themes directly following each session, as well as multiple reviews of the session notes, audio recordings, and written transcriptions.

After finalizing the coding schemes, two authors (T.W. and H.M.) used Atlas.ti Version 1.0.48 (2013, Scientific Software Development GmbH, Berlin) to code quotations within the transcripts. Different codes could be applied to the same segment of dialogue. Both authors (T.W. and H.M.) coded all transcripts and reached consensus on coding discrepancies. Ten themes were identified.

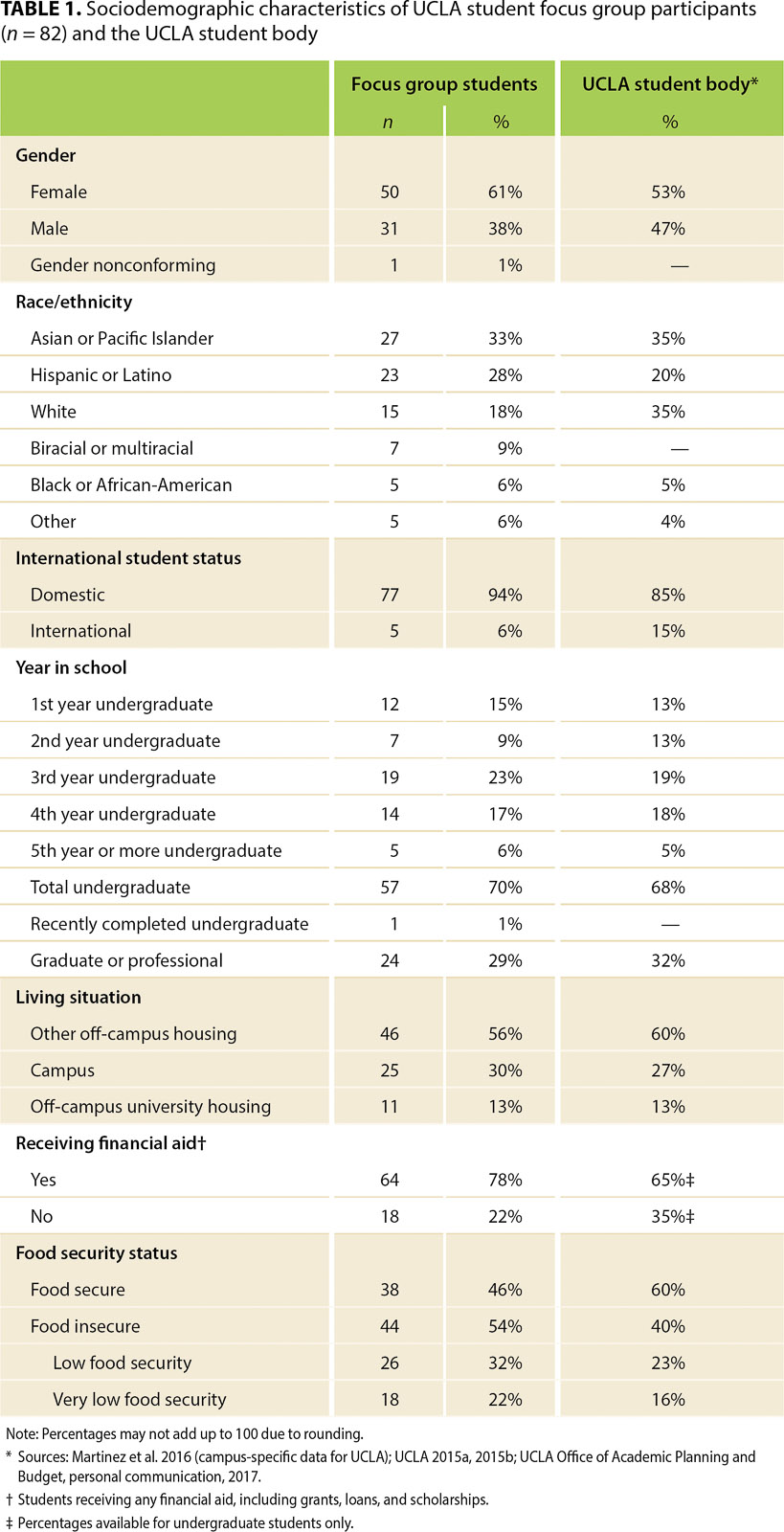

Low and very low food security

Participant characteristics are presented in table 1. According to survey responses to the USDA six-item food security survey module (USDA 2012), 44 participants, or about 54%, were classified as food insecure: 32% experienced low food security (defined as reduced diet quality, variety, or desirability) and 22% experienced very low food security (defined as skipping or reducing the size of meals).

TABLE 1. Sociodemographic characteristics of UCLA student focus group participants (n = 82) and the UCLA student body

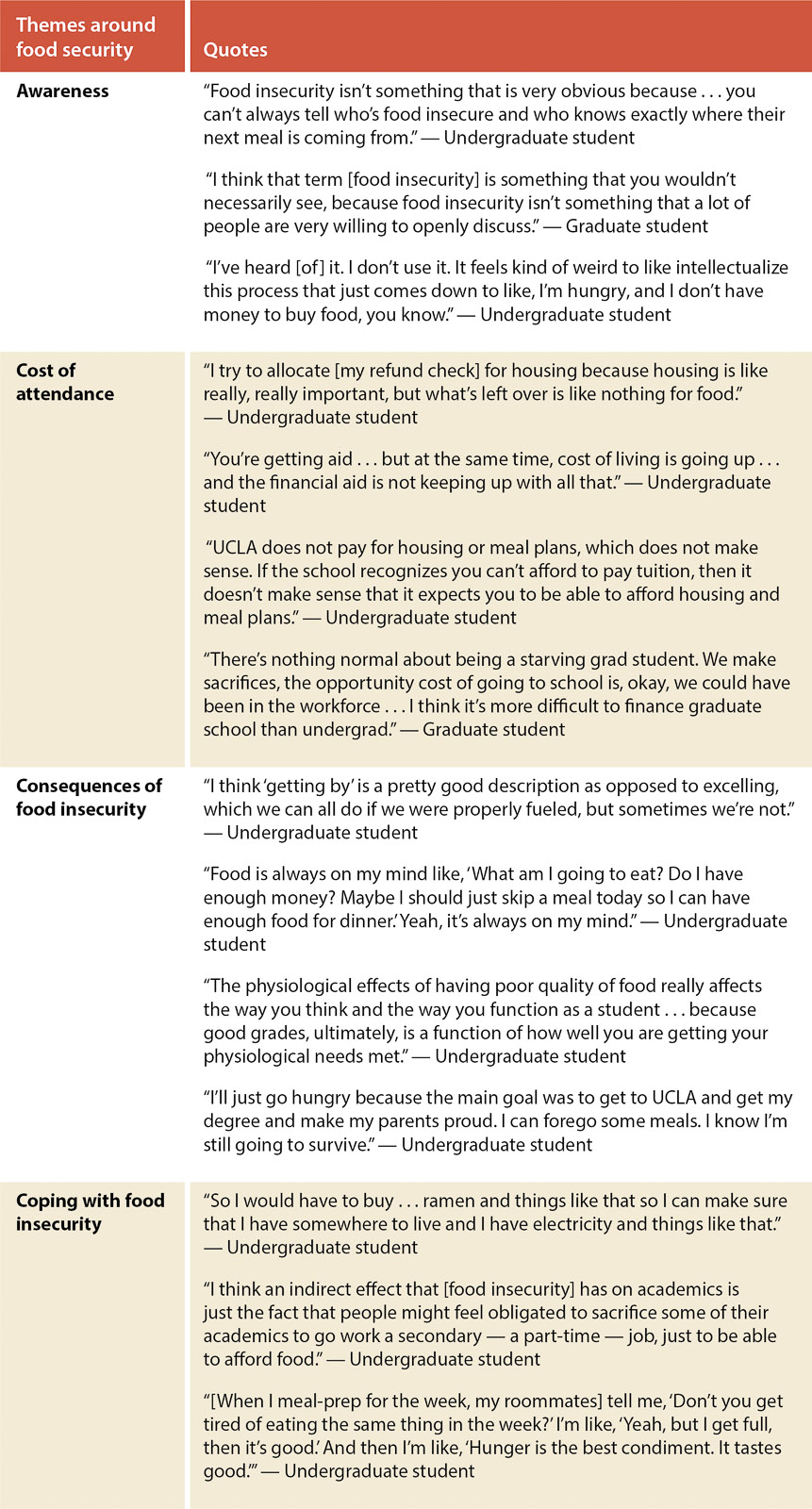

Food insecurity themes

The focus groups discussed several themes around food insecurity, including student awareness, cost of university attendance, consequences, and coping. Illustrative student quotes are presented in figure 2.

Awareness of food insecurity

Students were very aware of socioeconomic inequality among students, which included the ability to afford food. Students did not use the term “food insecurity,” but most had heard of the term and were aware of its approximate definition. Many students had either experienced food insecurity or knew that it existed among their peers. However, students spoke about food insecurity as an invisible issue on campus that was not openly discussed, and they expressed a desire for spaces to openly discuss food insecurity and other basic needs issues (i.e., housing and finances).

Students recognized the end of the academic quarter, academic breaks/holidays, and summer as times when they were more likely to experience food insecurity. Undocumented, commuter and international students were identified as highly vulnerable to food insecurity. Many students had heard about the CPO Food Closet but generally were not aware of other campus food resources unless they had personally used them. Students wanted more awareness and outreach around existing free food resources for struggling students.

Students who had experienced food insecurity reported they often relied on campus free food resources. One such resource, the UCLA Community Programs Office Food Closet (above), takes food donations and provides free food to any UCLA student in need.

Cost of attendance

Students described the high cost of attendance (tuition and fees, books and supplies, housing and food, transportation, and personal expenses) as the primary cause of food insecurity either personally or among their peers. They were particularly concerned about high tuition and fees and high rents in nearby neighborhoods. For many students, financial aid was not sufficient to cover the cost of attendance, and students often prioritized food last. Many students expressed concern about not having enough money to absorb unexpected costs such as medical bills.

In general, students did not feel confident budgeting, especially because they received their financial aid disbursement in a single payment per academic quarter. There was a range of viewpoints on the acceptability of loans, with some students accepting they would have a heavy loan burden after graduation and others unwilling to accept any student loans. Graduate students generally felt they had less financial support from the university than undergraduate students had, despite often having additional financial responsibilities such as a spouse and dependents.

Consequences of food insecurity

Many students reported choosing cheaper, less nutritious foods and skipping meals. For struggling students, worrying about food was a persistent stressor that negatively impacted their academic performance. Some students reported spending a substantial amount of time and energy worrying about getting enough food or where their next meal would come from. They reported both mental and physical health impacts, including stress, inability to focus on their work, fatigue and lack of energy, irregular sleep patterns, irritability, depression, headaches, and weight gain linked to inadequate food intake. Students also described missing out on social opportunities, such as eating with friends in the dining halls or at restaurants due to financial constraints (e.g., running out of meal swipes or wanting to save money).

Coping with food insecurity

A majority of students attended events on and near campus to get free food. Students who had experienced food insecurity reported they often relied on campus free food resources to help them get by, especially the CPO Food Closet and 580 Café, a nearby community study space that offers free snacks and meals for students. A few students discussed preparing inexpensive staple foods, such as beans and rice, or snacking on granola bars to get through the day. Some students talked about working part-time jobs to help afford food and other expenses, but this caused more stress, which impacted academic performance. Students were hesitant to ask for help, but often relied on friends for assistance. For example, “swiping” friends with campus IDs into campus dining halls was a common strategy to help friends living both on and off campus. Some students normalized the struggle to eat as part of the college experience.

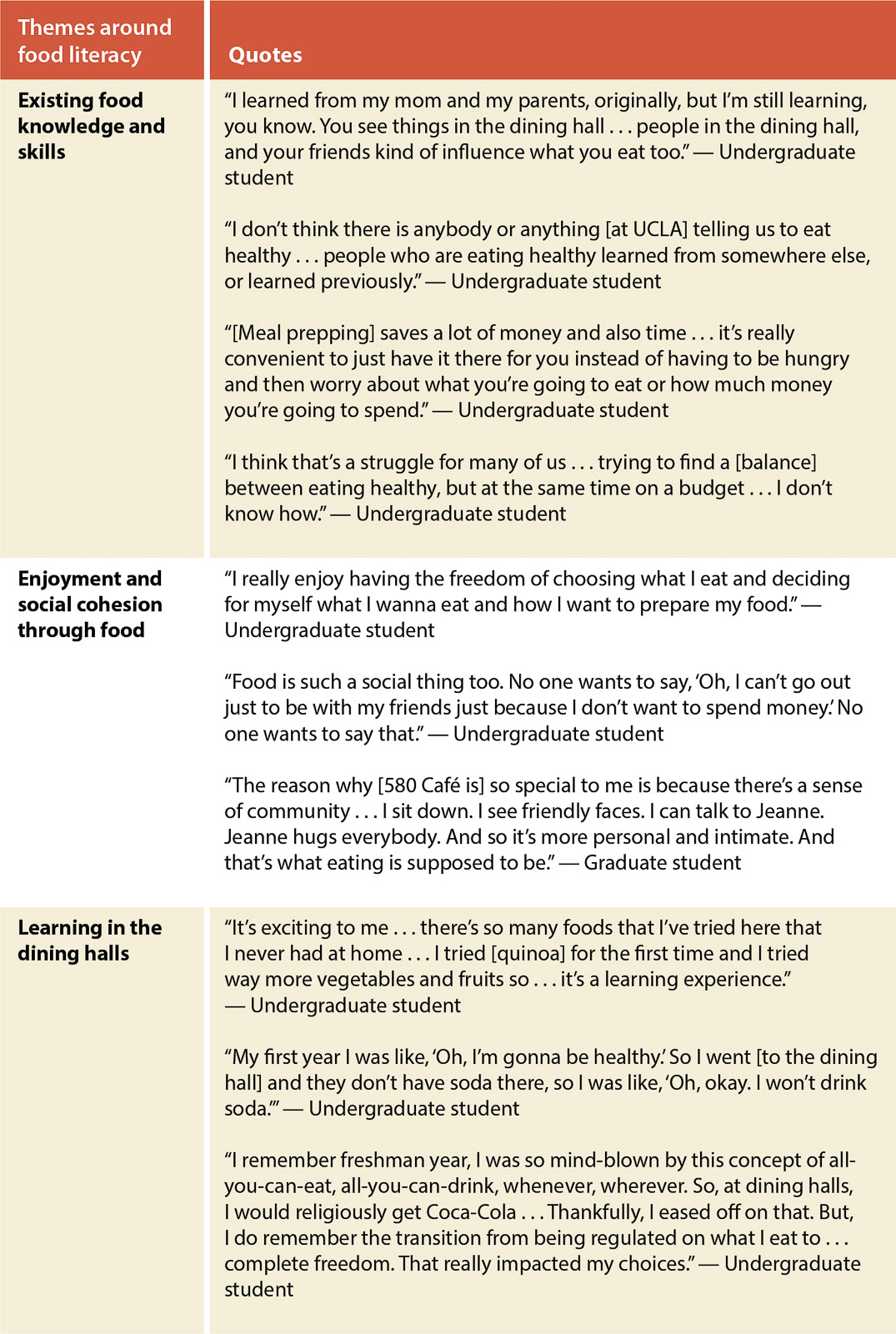

Food literacy themes

Students discussed several themes around food literacy, including existing knowledge and skills, enjoyment and social cohesion, and learning in the dining halls. Illustrative student quotes are presented in figure 3.

Food knowledge and skills

Students identified numerous sources of food knowledge and skills, most often mentioning family, peers, news media, and UCLA courses. They also mentioned entertainment media (e.g., cooking shows), social media (e.g., Yelp, Facebook), smartphone applications (e.g., MyFitnessPal), scientific journals, UCLA resources (e.g., dietician), public health campaigns, advertising, travel, and K-12 education.

Students described family customs and culture as the foundation of food literacy and said they continued to develop their food knowledge and skills. Many discussed learning about food by observing others in the dining halls, discussing peers' dietary habits, and cooking with friends and roommates. Students commonly reported watching food documentaries and cooking shows, and many reported searching online for recipes, nutrition, and other food-related information. Although students cited UCLA courses as a credible and influential source of academic information about food, the large majority of students said they received little or no practical skills-based training from UCLA. Few students mentioned learning about food and nutrition as part of their K-12 education.

Students discussed their confidence and ability with respect to the food literacy domains of planning, selecting, preparing, and eating food. Many students described strategies for protecting diet quality and reducing costs. For some students, this meant prioritizing time to eat in the dining hall, while for others it involved prepping meals on Sundays or finding free food resources on campus. Others said they felt overwhelmed or time restricted and thus were less able to balance their resources with their nutritional needs. They reported skipping meals or choosing less preferable (e.g., unhealthy, low-quality, not filling) foods.

Food enjoyment, social cohesion

Students referred to cooking and eating as a way to bond and express love. They also discussed college and early adulthood as an exciting and formative time in which they were able to determine their own food preferences and priorities, explore new cuisines, and build community through food. Some students said they enjoyed cooking as a way to relax, relieve stress, and be creative.

The majority of students reported spending time dining, discussing, and preparing food socially with their peers. They explained that sharing food can be a positive way for students to come together in a stressful and competitive university environment. Bonding over food and cooking was even mentioned as an opportunity to build friendships. Students struggling with food insecurity said resources that supported family-style eating provided the added value of social interaction and support.

Learning in the dining halls

Residential undergraduates (with campus-provided meal plans) discussed how the food and beverages offered in the dining halls not only expanded their knowledge of healthy food but also “nudged” them into healthful habits. They said signage and menu labeling improved their awareness of nutrition and sustainability issues. However, many students expressed challenges with transitioning to a new food environment and a desire for culturally familiar food described as “comfortable.” Students explained that their new independence combined with an overabundance of food in dining halls required learning and effort to self-regulate eating behaviors.

The university's role

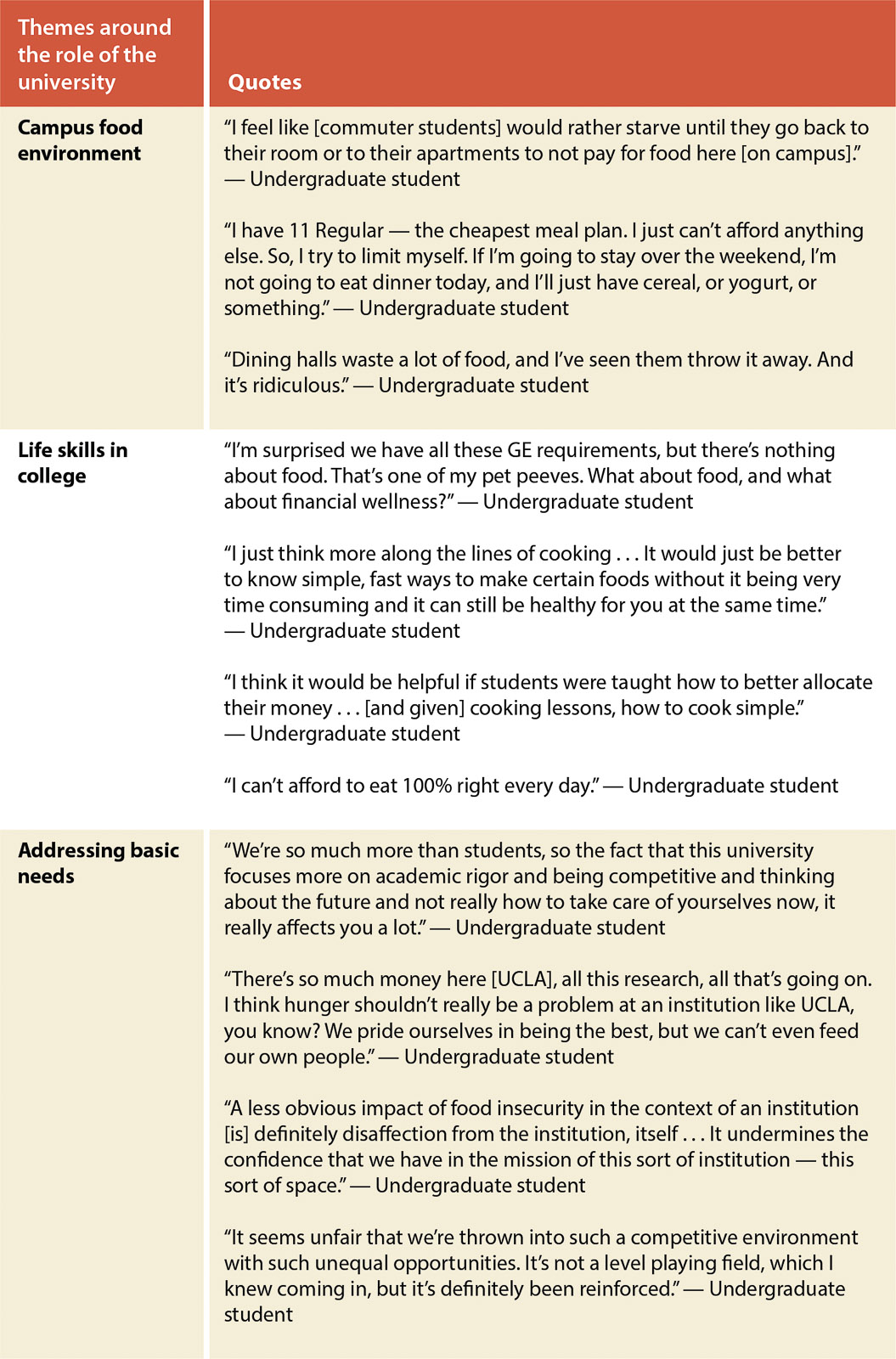

Students discussed several themes that overlapped both food insecurity and food literacy. Unifying themes included the campus food environment not meeting student needs, a desire for practical financial and food literacy “life skills” training, and skepticism about the university's commitment to adequately address student basic needs. Illustrative student quotes are presented in figure 4.

Fig. 4. Themes and quotes around the role of the university among focus group participants (n = 82).

Campus food environment

Many students living in campus residence halls had positive comments about the quality of the food in the dining halls but expressed concerns about the tiered meal plan structure — having a meal plan did not guarantee food security. Students discussed choosing meal plans based on their financial means and not on nutritional needs. For instance, some students reported buying the most limited meal plan (11 meals per week) because it was the cheapest option. Students also reported they lacked access to kitchen space to prepare food to supplement meal plans or cook with friends. A majority of students also perceived large amounts of food waste on campus and felt that some food, especially in the dining halls, could be recovered and redirected to students in need.

Beyond the dining halls, students overwhelmingly said that food on and near campus did not meet their needs. Food perceived to be healthy was often cited as expensive or not “filling” (e.g., salads). Food that was affordable and “filling” was often perceived as unhealthy and low quality (e.g., $1 beefy burrito). Consequently, many students brought food from home, bought less preferable foods, found free food options, or skipped meals. Many students were willing to travel beyond the surrounding campus neighborhood to find affordable and culturally appropriate food outlets (e.g., Asian markets, discount stores).

Through the UCLA Farmers Market Gleaning Program, students volunteer with Food Forward, a Los Angeles-based nonprofit organization that collects produce from local farmers markets, below, that would otherwise go to waste and distributes it to people in need through food pantries, shelters, senior homes and other channels. The program was started in 2015 by author Tyler Watson and undergraduate student Savannah Gardner, left, in collaboration with the student group Swipe Out Hunger. It now delivers more than 400 pounds of fresh produce to UCLA students each week and also hosts cooking and nutrition demonstrations.

Life skills in college

Students identified college as an appropriate place to learn practical life skills, including food planning and preparation. They said that food-related issues became more salient in college, and they expressed the need for the university to provide additional food education and training. Many students wanted to learn to budget and cook simple nutritious meals. They were frustrated with intellectually knowing the “right choice” but not having the skills or resources to act on that knowledge.

Students discussed various formats for receiving practical food instruction, ranging from a required general education course to pop-up cooking demonstrations on campus. Many students said they thought a practical one-unit undergraduate life skills course should be required to both support health-promoting behaviors among students and demonstrate the university's commitment to student well-being. Students identified the transition from living in university residence halls to living off campus as a critical time to receive this instruction.

Addressing basic needs

Many students were skeptical of the university's commitment to adequately and effectively address student basic needs. A prevailing attitude was that the university placed too much importance on academic performance and research efforts and not enough on prioritizing struggling students and a holistic student experience. Students discussed key areas in which the university was not addressing their needs: inadequate financial aid allocations, unaffordable housing costs, inflexible meal plans, high food costs on campus, and lack of opportunities to learn life skills, including financial and food literacy. Many students did not believe the university would address these needs, which negatively affected their sense of belonging at the university. Some students were hopeful about the increasing awareness of student food insecurity and other struggles such as homelessness.

UCLA tuition and living costs

UCLA undergraduate student tuition and fees ($12,836 for the 2016–2017 academic year) are now twice what they were in 2006–2007 in absolute dollars, largely as a result of state funding cuts to the UC during the Great Recession (Mitchell et al. 2014; UCLA 2016; UCOP 2016). Following a 6-year tuition freeze, UC Regents have voted to increase tuition and fees by 2.5% for the 2017–2018 academic year (UC Board of Regents 2017; UCOP 2016).

In addition to rising tuition and fees, UCLA is located in one of the highest-cost-of-living regions in Los Angeles (Apartment List Inc. 2017). According to the 2016 UC Cost of Attendance Survey, UCLA students living in a one-bedroom apartment without roommates paid $1,342 per month, and students with one roommate paid $951 per month. The all-student rent average was $840 (ranging from zero to six-plus roommates), making it the second-highest rent average in the UC system, below only UC Berkeley (UCOP 2017).

Many students receiving financial aid felt the support was insufficient to meet the cost of attendance, currently estimated at $34,088 at UCLA (UCLA 2016). Their concern is consistent with Kelchen et al. (2014), who found that over half of U.S. postsecondary institutions underestimated 9-month living cost allowances for students living off campus by an average of $3,000, assuming a single-efficiency apartment. These student concerns about actual cost of attendance led to improvements in how the UC system asked students about their cost of living in the 2016 UC Cost of Attendance Survey. Specifically, the question of food expenses in the last month was updated to food expenses in the last week based on student and staff input (Ruben Canedo, UC Basic Needs Co-Chair, personal communication, Mar. 15, 2017).

Food insecurity normalized

Taken together with the UC Student Food Access and Security Study, the findings from our study suggest that students across the UC system struggle to meet their basic needs, and food is the easiest thing to sacrifice. It is possible that struggling with food insecurity in higher education settings has been normalized among students, which may help explain why, until recently, the issue has been unacknowledged and therefore largely unaddressed.

Students in this study described struggling to afford food as a persistent stressor that affected both academic performance and mental and physical health, which is consistent with the literature (Freudenberg et al. 2011; Gundersen and Ziliak 2015; Martinez et al. 2016; Patton-Lopez et al. 2014; Seligman and Schillinger 2010). A recent UC study found that students experiencing food insecurity were twice as likely to have feelings of depression than their food-secure counterparts (Ritchie and Martinez 2016). In our study, students felt they missed out on social opportunities, such as dining with peers, which are important for building social ties in a college environment (Umberson and Montez 2010). Limited opportunities to create social ties in college may affect a sense of belonging and increase a student's intention to drop out of college (Langhout et al. 2009).

Food training, cooking skills

A majority of students in our study discussed wanting more training and skills around food preparation and budgeting. The UC Student Food Access and Security Study also found that across the UC system students wanted university assistance with learning to cook cheap, healthful meals and to budget with limited resources (Martinez et al. 2016). Previous research suggests people with high or moderate levels of cooking, food preparation, and financial skills are less likely to experience food insecurity than people with lower skill levels (Gorton et al. 2009).

With support from the UCLA Healthy Campus Initiative and David Geffen School of Medicine, a teaching kitchen pilot program was launched in spring 2017 for students in health-related fields. Based on the high level of interest and positive feedback, organizers hope to expand the program.

College may be a critical time for developing food literacy, as 57% of food insecure UC students reported that they were new to experiencing food insecurity (Martinez et al. 2016). Also, improving food literacy could help address the widely held student perception that healthy food is more expensive. Several UC campuses have launched academic and community programs to increase student food literacy and improve student food security.

Limitations

This study had several limitations. We used convenience and purposive sampling to recruit focus group participants, which may limit generalizability to broader student populations. Participants were more likely to be female, minority race/ethnicity and receiving financial aid than the general student population. Because two focus groups intentionally included students who use free food resources, the overall proportion of study participants who had experienced food insecurity (54%) was higher than in the UC Student Food Access and Security Study (42%) (Martinez et al. 2016); however, the prevalence of food insecurity among students in the other nine focus groups was 39%. Additionally, study participants may have been more interested in and aware of food issues. Lastly, it is important to consider issues of conformity and censoring within focus group studies. Despite efforts to maximize homogeneity within groups and the apparent range of experiences and opinions heard, some students may have been inclined to match their experiences to those already stated or refrain from sharing unpopular attitudes or beliefs (Morse 1994).

Statewide challenge

Meeting student basic needs is gaining recognition as a major challenge across institutions of public higher education of all sizes, and efforts are under way to comprehensively work toward student basic needs security. With support from the UC Global Food Initiative, all 10 UC campuses are conducting academic and administrative research; implementing both short-term (e.g., food pantries) and long-term (e.g., Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, SNAP, registration) services; improving systems practices (e.g., contracts with food vendors); and leading policy advocacy across campus, UC system, and state government levels. In 2017, the institutions of higher education in California — UC, state universities, and community colleges — formalized a partnership to develop statewide policy solutions to improve the lives of their students. Further research is needed to better understand the student experience of food insecurity and to assess the feasibility and effectiveness of interventions aimed at reducing food insecurity among college students nationwide.