All Issues

UCCE efforts improve quality of and demand for fresh produce at WIC A-50 stores

Publication Information

California Agriculture 69(2):105-109. https://doi.org/10.3733/ca.v069n02p105

Published online April 01, 2015

NALT Keywords

Abstract

In 2005, the Institute of Medicine recommended major revisions in the food packages provided by the federal Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC), leading to new regulations that allow participants to purchase a wide variety of fruits and vegetables with their vouchers. In support of this policy change, UC Agriculture and Natural Resources Cooperative Extension (UCCE) developed educational materials to promote fresh produce among WIC participants and offered postharvest handling training at WIC-only stores, known as A-50 vendors, in order to improve produce quality. A survey conducted after the educational sessions found that WIC participants had increased knowledge of produce and A-50 vendors showed improved postharvest handling after the education sessions. This research demonstrates that combining nutrition education with postharvest handling curriculum can lead to a successful educational program that supports increased demand among WIC participants for fresh produce.

Full text

In 2005, the Institute of Medicine (IOM) recommended major revisions in the food packages provided by the federal Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) (IOM 2005). These recommendations resulted in the first comprehensive changes since 1980 in the foods provided by WIC, a food assistance program that serves low-income pregnant, breastfeeding or postpartum women; infants; and children up to 60 months of age with a nutritional risk (USDA 2007). Revisions to the WIC food packages (the specific foods and amounts that may be purchased with vouchers each month) were needed to help this vulnerable group of participants achieve dietary intakes in accordance with the Dietary Guidelines for Americans (USDHHS and USDA 2011).

Based on evidence that WIC populations do not consume sufficient amounts of fruit and vegetables (IOM 2005), interim federal regulations were implemented to allow WIC to issue cash-value produce vouchers for $10 a month in the women's packages and $6 a month in the children's packages (USDA 2007). WIC vendors are required to stock a minimum of two different types of fruit and vegetables, although the intent is that WIC participants will have access to a wide variety of fruit and vegetables. The expectation is that participants will receive nutrition education at WIC sites on how to shop for produce to get the maximum nutrition for their WIC vouchers.

By October 2009, WIC agencies in all 50 states, tribal lands and U.S. territories had implemented the revised WIC food packages. The impact of this policy change on the retail environment where WIC shoppers use their vouchers appears to be positive, albeit modest — A-50 vendors, for example, installed coolers and began to carry a wider variety of produce (Hardesty et al. 2015). One study has published data on the revised policy's impact on dietary intake of WIC participants. In that study, small but significant increases in fruit and vegetable intakes were documented among WIC participants, as determined by cross-sectional phone surveys conducted in California in September 2009 and March 2010 (Whaley et al. 2012).

In support of the revised federal policy on WIC fruit and vegetable vouchers, UC ANR Cooperative Extension researchers created posters and fact sheets to promote nutrition education and increase demand for fresh produce among WIC participants.

About half of the more than 5,500 WIC- authorized vendors in California are large grocery stores that already carry a variety of produce and therefore are not affected by the federal requirement of stocking a minimum of two different types of fruit and vegetables. The other half includes smaller stores as well as the WIC vendors that have over 50% of their food sales from WIC items, known as A-50 vendors. Prior to the implementation of the new WIC produce vouchers, the A-50 vendors were not required to carry any fresh produce except carrots.

In 2010, a team of researchers from UC Cooperative Extension (UCCE) exploring the feasibility of a farm-to-WIC program conducted a survey in three California counties (Tulare, Alameda and Riverside) to determine interest among WIC clientele in purchasing locally produced fruits and vegetables, as well as the factors influencing produce choices (Kaiser et al. 2012). WIC participants reported a preference for fresh, good-quality produce, demonstrating the demand-side viability of a farm-to-WIC program. A companion paper in this issue discusses the challenges of meeting this demand through small-scale local farmers (Hardesty et al. 2015, page 98 ).

In this paper, we examine UCCE efforts to increase the demand for fresh produce among WIC participants through point-of-purchase education and to improve the quality of produce offered by A-50 vendors through postharvest handling training. In addition, we review the results of a small qualitative study we conducted in 2012 on WIC clientele shopping behavior to assess the WIC population's purchasing needs. The protocol for this study was approved by the UC Davis Institutional Review Board under exempt status.

Educational materials

The UCCE nutrition researchers developed educational materials primarily for use at the point of purchase (i.e., the cash register or counter where customers pay) in A-50 stores, but also for use in reinforcing nutrition education delivered at WIC offices. Based on the findings of the 2010 survey, the UCCE team identified the following 18 produce items to target for promotion and nutrition education via single-page fact sheets in English and Spanish: bell peppers, broccoli, cabbage, cactus leaves (nopales), cantaloupe, carrots, collard greens, grapes, green beans, lettuce, mustard greens, oranges, spinach, strawberries, sweet potatoes, tomatillos, tomatoes and watermelon.

Fact sheets developed by UCCE researchers provide nutrition information and tips on how to choose, store, prepare and serve different fruits and vegetables.

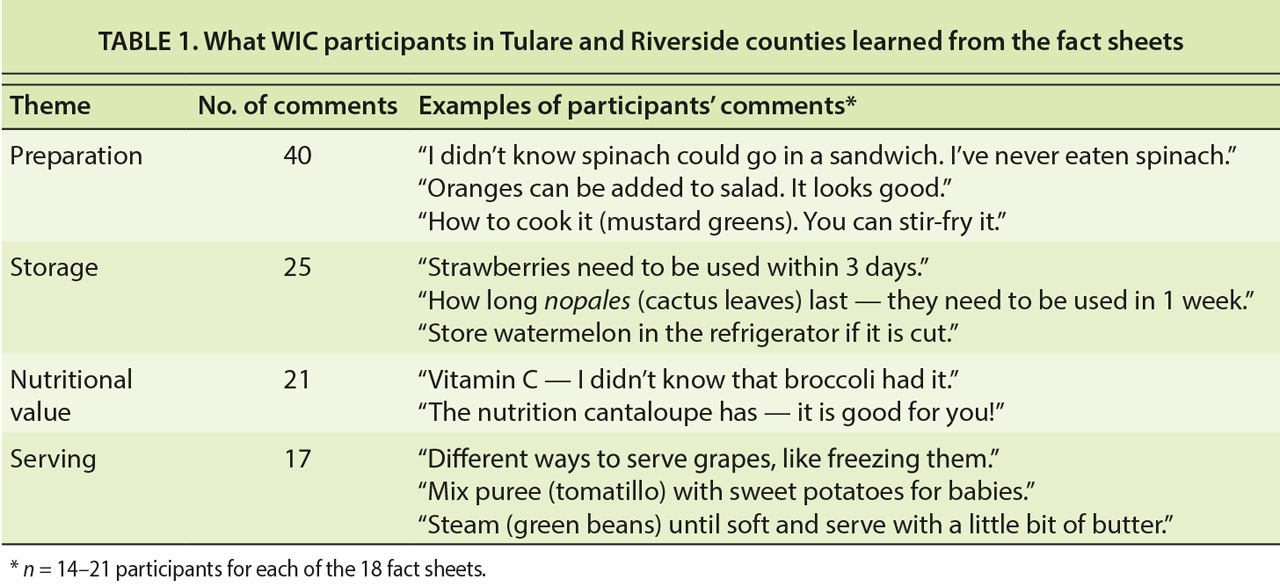

Each fact sheet is designed for a limited-literacy audience and features a single fruit or vegetable with tips on how to choose, store, prepare and serve the food in ways that appeal to young children (ucanr.edu/sites/comnut/mothersyoungchildren/Fact_Sheets/). UCCE researchers and assistants conducted cognitive testing of the fact sheets at the WIC sites in Tulare and Riverside counties, interviewing in person, one-on-one, between 14 and 21 different WIC participants in English or Spanish for each of the 18 fact sheets. UCCE staff used open-ended questions to probe for understanding of the words, concepts and pictures used in the fact sheets and to determine what new information was gleaned. During the interviews, participants shared their ideas and provided additional kid-friendly tips for preparing or cooking the vegetable or fruit.

Table 1 shows what the participants learned from the fact sheets (in rank order) about preparation, storage, nutritional value and serving of the produce items. Most participants found the fact sheets useful, especially the nutrition information and the tips on how to choose, store and prepare produce. Most said they learned something new from the fact sheets; in particular, several people were surprised at the differences in the shelf life of various fruits and vegetables. Many participants mentioned that they had never eaten the vegetable before (collard greens, mustard greens, cactus leaves, sweet potatoes and spinach) but liked the tips on how to prepare them. Some were surprised that the fruits or vegetables can be served to infants, particularly bell peppers, green beans, collard greens, tomatillos and watermelon.

Like the California WIC program, UCCE has found that a learner-centered approach (one in which instructors use a variety of teaching methods to facilitate student learning) is more effective in improving fruit and vegetable intake (Gerstein et al. 2010; Kaiser et al. 2007) than a traditional lecture-oriented approach. The produce fact sheets can be used to provide information that is immediately useful to a WIC participant who expresses interest in introducing that food to her child. The “What's In Season Now?” poster, another educational resource created by the UCCE project team, is a colorful visual showing produce available during each season. It can be used as an activity for WIC participants to pair up and brainstorm how they can use seasonally available fruits and vegetables to prepare meals for their families.

Postharvest handling training

Since produce quality is an important factor affecting WIC customer purchases, and handling perishable fresh produce was a new task for many A-50 store employees, UCCE gave produce-handling trainings to WIC distribution center personnel and A-50 vendors. Between 2010 and 2012, a UCCE specialist visited 15 A-50 vendors in Alameda, Tulare and Riverside counties to assess the need for employee training. Based on the specialist's observations and discussions with A-50 store personnel, the project team developed workshops that focused on produce handling scenarios and how to minimize losses. Although the main focus was on handling the produce received by the stores, the trainings also addressed produce handling from harvest through distribution to the stores. UCCE staff covered topics such as temperature management with limited cold room space available in the stores, control of water loss, compatibility issues with a focus on ethylene-sensitive produce (those damaged by exposure to ethylene gas, such as lettuce and carrots), minimizing decay, managing product turnover and maintaining postharvest conditions to retain nutrients, among others.

The one-day workshop trainings at WIC distribution centers involved mostly female employees. Multiple trainings were held: one session with five employees, two sessions with 25 employees each, and a final session involving over 70 employees, with some attending via remote access. At the trainings, UCCE staff distributed photos with examples of good and poor handling practices occurring in the A-50 stores and facilitated discussions with store employees. For these sessions, PowerPoint presentations, handouts and thermometers were provided. To stimulate problem solving and discussion, the presentations incorporated some of the photos taken during the UCCE specialist's store visits.

Proper fruit and vegetable storage is an example of the type of challenges faced by A-50 vendors that UCCE staff addressed in the trainings. In most of the A-50 stores, there are two temperature options: refrigerated shelf space at about 41°F (5°C) or holding at room conditions, 59°F to 86°F (15°C to 30°C), depending on the season and the store's location. The proper option for cool season vegetables and packaged salads and other fresh-cut products is the refrigerated cabinet. But for chilling sensitive products, such as tomatoes, there is no single correct option, as ripeness, time and ambient temperature will be considerations. Another problem for stores is that fruit may arrive at the store mature, but not ripe or ripened and ready to eat. Managing the ripening process if needed, and then holding ripe fruit in refrigerated shelf space, was discussed as a strategy to prevent fresh produce losses. Limes, which do not require ripening, can be problematic for a different reason: in refrigeration they turn brown due to chilling injury, while at ambient conditions they turn yellow. The UCCE specialist suggested that employees use a technique of intermittent warming, or switching the limes back and forth between the two temperature options. These examples illustrate some of the problems that were discussed with the objective of finding workable solutions to minimize fresh produce losses.

As a result of the new policy on WIC produce vouchers, many A-50 vendors in California began to carry a wider variety of fruits and vegetables.

Over the 2-year period, an increased level of knowledge was noticeable among employees who participated in repeat discussions at the stores or the formal training offerings. Their questions about fresh produce handling became more detailed and specific as their experience and understanding grew. The UCCE specialist prepared four narrated PowerPoint presentations using A-50 vendor produce examples and answers to common postharvest handling questions for continuing employee trainings (postharvest.ucdavis.edu/libraries/video/PHVideosWIC/).

Survey of produce purchasing habits

To assess the need for future WIC education sessions, UCCE researchers conducted a qualitative survey in March and April 2012 on the spending habits of WIC shoppers. Data was collected from WIC participants in Alameda, Riverside and Tulare counties, who were recruited while they waited to pick up WIC vouchers. Inclusion criteria were having at least one child aged 12 to 47 months currently enrolled in WIC; being the main WIC shopper in the household; and being sufficiently fluent in Spanish or English to complete the study. UCCE staff members read aloud the surveys, which lasted 15 to 20 minutes, to participants in the waiting areas of WIC offices or in a closed WIC classroom, depending on the preferences of the participant. Surveys conducted in Spanish were translated into English and qualitatively analyzed for purchasing trends.

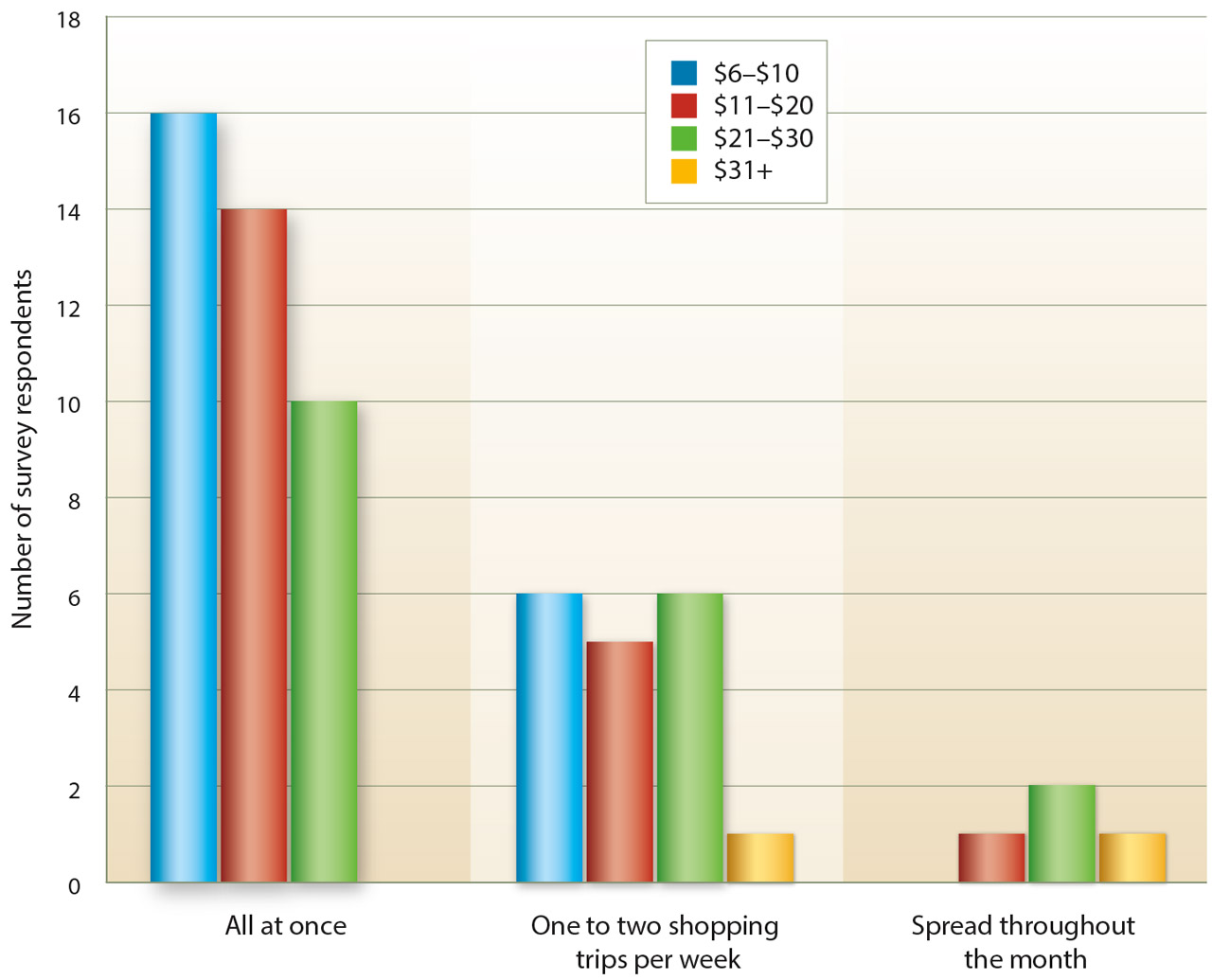

The sample included a total of 62 WIC participants. Of the 62 respondents, five identified as white/non-Hispanic and 56 identified as Latino/Hispanic (missing data on one participant). In California as a whole, roughly 80% of WIC participants report Hispanic ethnicity (Whaley 2012). The mean age of respondents was 29.2 years. A trend was observed towards a positive relationship between the dollar value of the produce voucher and frequency of spending: the smaller the dollar value of the voucher, the more likely that the entire voucher is spent in a single visit (fig. 1). For participants receiving between $6 and $10, this single point of spending suggests a peak period of fruit and vegetable purchasing and subsequent consumption. However, this is not dependent on when the vouchers are issued during the month. When participants were asked how soon they spent the vouchers after they received them, those receiving $6 to $10 (65% of survey respondents) most frequently replied, “it varies.” Eighty-five percent of participants reported spending their fruit and vegetable vouchers at the same store where they spend other WIC vouchers.

Fig. 1. Frequency of WIC fruit and vegetable voucher spending in Alameda, Tulare and Riverside counties based on dollar value of vouchers received the previous month (n = 62).

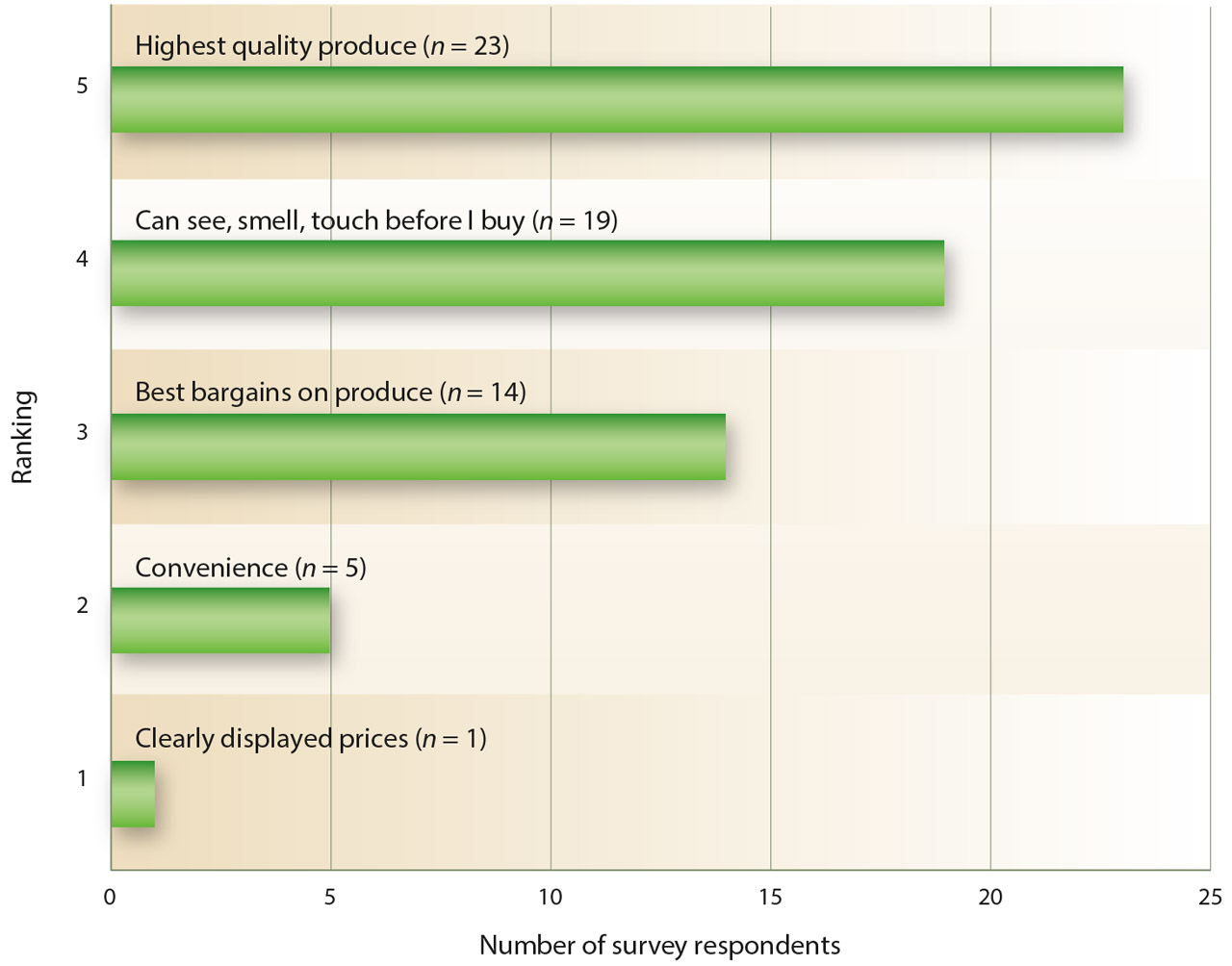

Based on their observations of the store layout of the local A-50 vendors and conversations with WIC staff, UCCE nutrition researchers generated a list of five factors that might influence WIC participants’ produce purchasing decisions. Participants were given this list and asked to rank the factors, with 5 being most important and 1 least important. Responses from a total of 62 participants were summed and the results show that quality of produce received the highest ranking and clearly displayed prices received the lowest (fig. 2).

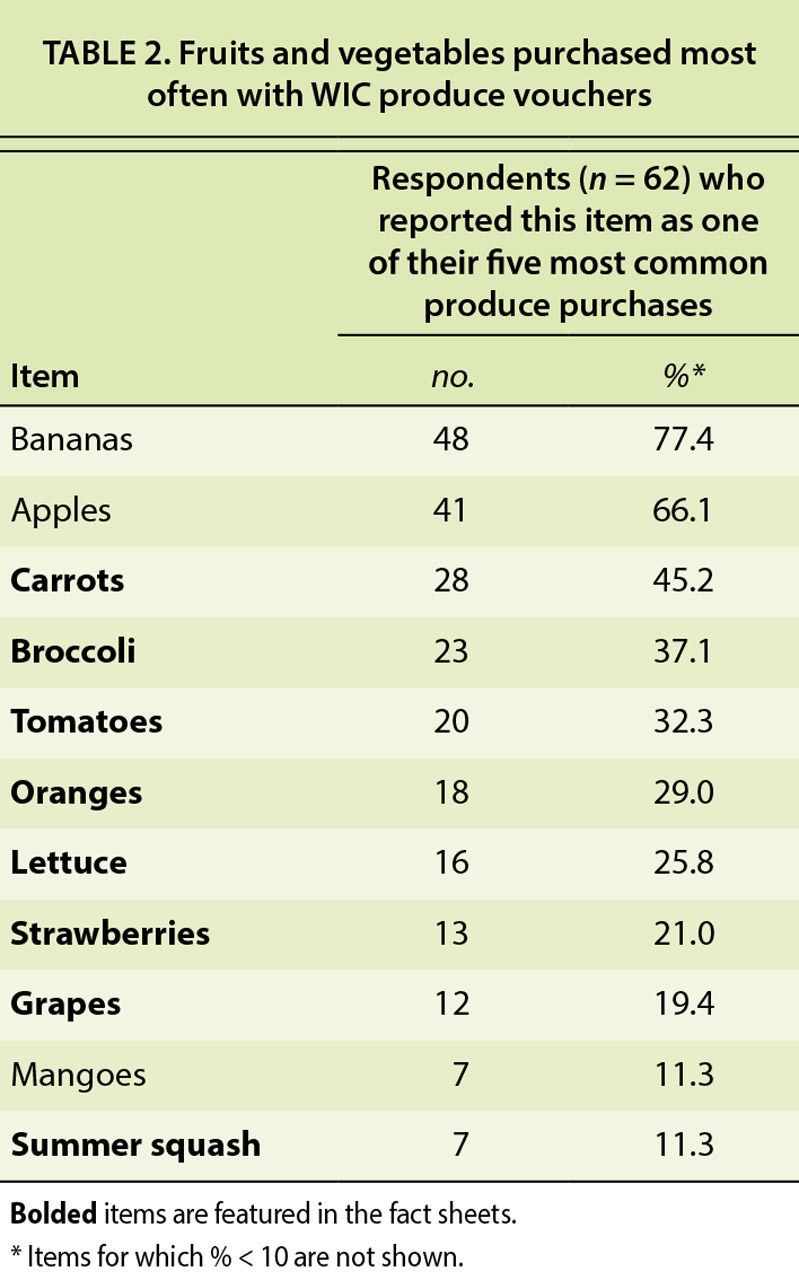

Overall, the quality of fruits and vegetables consistently ranked as very important to WIC participants. When asked to list the five fruit and/or vegetable items bought for the family most weeks and used most often, participants reported that they spend WIC vouchers more frequently on fruits than on vegetables, with bananas (77%) and apples (66%) being more frequent than carrots (45%) and broccoli (37%) (table 2). Seven of the top 11 items purchased were produce items featured on the fact sheets.

Participants were shown examples of the fruit and vegetable fact sheets. When asked if they would like to receive this kind of information, all but three (92%) participants responded yes. Following a “yes” response, participants were asked in what format they would like to receive the sheets; 77% preferred paper handouts, while the rest preferred other formats such as Facebook, websites and mail.

Future education and research needs

The research described here demonstrates the success educational efforts can have in support of the revised federal policy on WIC produce vouchers. These educational approaches should be seen as individually effective and complementary. For example, availability of fresh fruits and vegetables has the strongest influence on where WIC participants decide to shop, and they reported spending fruit and vegetable vouchers where they spend other WIC vouchers. If produce in A-50 stores is unappealing due to poor handling, for example, WIC participants may avoid the store altogether. A-50 vendors would then lose both produce voucher and other WIC food voucher profits.

Additionally, the results of our survey on produce shopping habits show that many of those receiving limited fruit and vegetable vouchers spend them all at once, suggesting produce is not eaten immediately after purchasing, but rather may sit for days in the home. This highlights the necessity of postharvest handling training to maintain the highest possible quality at purchase to ensure needed shelf life in the home refrigerator or cabinet. If educational efforts continue or expand to other A-50 vendor locations, the distribution of the fruit and vegetable fact sheets should remain, combined with postharvest handling training.

To further support and evaluate implementation of the WIC produce voucher policy, additional research is needed in the following areas: (1) Examining fruit and vegetable purchasing behaviors in the WIC population with earned income; (2) determining the perceived value of different locally sourced produce items found in A-50 stores; and (3) identifying changes in produce purchasing habits and dietary intake attributable to enrollment in WIC.

Educational approaches should provide guidance specifically tailored to the needs of the target population. The point-of-purchase educational materials and postharvest training of WIC A-50 store employees in this study were designed to respond to the food preferences and dietary patterns of WIC participants in California. This project demonstrated that UCCE programs, specifically teaming up nutrition with postharvest handling, can lead to a successful educational program that supports increased demand for fresh produce.