All Issues

Predicting invasive plants in California

Publication Information

California Agriculture 68(3):89-95. https://doi.org/10.3733/ca.v068n03p89

Published online July 01, 2014

NALT Keywords

Abstract

Preventing plant invasions or eradicating incipient populations is much less costly than confronting large well-established populations of invasive plants. We developed a preliminary determination of plants that pose the greatest risk of becoming invasive in California, primarily through the horticultural industry. We identified 774 species that are invasive elsewhere in Mediterranean climates but not yet invasive in California. From this list, we determined which species are sold through the horticulture industry, whether they are sold in California and whether they have been reported as naturalized in California. We narrowed the list to 186 species with the greatest potential for introduction and/or invasiveness to California through the horticultural trade. This study provides a basis for determining species to evaluate further through a more detailed risk assessment that may subsequently prevent importation via the horticultural pathway. Our results can also help land managers know which species to watch for in wildlands.

Full text

Plants have been transported around the world for centuries, as agricultural commodities, ornamental species or inadvertent contaminants of imported materials. Naturalized plants are those that have spread out of cultivated areas, including gardens, into more wild areas, and invasive plants are the subset of naturalized species that cause ecological or economic harm. In general, only a small proportion of plants introduced into a new region have been invasive plants. However, the number of invasive plants with horticultural origin is high, making it critically important to natural resource managers, ecologists and policymakers to predict which newly introduced species pose the greatest risk of escape and invasion.

Giant reed (Arundo donax) infesting a wetland area in Southern California. Giant reed was introduced as both an ornamental and erosion control species and is now one of the most invasive species in the state.

The geographic diversity of California has led to broad evolution in native plants. California has approximately 3,400 species of native plants, of which 24% are found only in the state (Baldwin et al. 2012). However, California is also something of a hotspot for nonnative plants, with over 1,500 nonnative species naturalized, weedy in agricultural systems or invasive in natural areas (DiTomaso and Healy 2007). As a result, California not only faces a high risk of escape, establishment and invasion of introduced ornamental plants, but also has a high proportion of native species threatened by invasive plants.

Within California, there are two lists that identify invasive plants. First, based on 13 questions that assess impacts, invasiveness and distribution, the California Invasive Plant Council's list includes 214 species that cause ecological harm in the state's wildlands (Cal-IPC 2013). Approximately 63% of these species were deliberately introduced to California, mostly as ornamental plants (Bell et al. 2007). Second, the California Department of Food and Agriculture (CDFA) Noxious Weed List primarily lists plants that cause, or have the potential to cause, economic damage to the state's agricultural industry; CDFA has legal authority to regulate plants on this list through Section 4500 of the California Code of Regulations (CDFA 2013). Because the criteria for these lists have a different focus, the listed species overlap but are not the same. Few species derived from the horticultural trade are included on the state Noxious Weed List.

The horticultural trade is one of the major pathways for invasive plants in California and elsewhere (Drew et al. 2010; Okada et al. 2007; Reichard and White 2001). For example, higher market frequency (as measured by availability in seed catalogs) and lower prices were shown to be good predictors of a plant's probability of invasion in Britain (Dehren-Schmutz et al. 2007). Horticulture is also a major agricultural sector in California, accounting for $2.5 billion in sales in 2011 (CDFA 2012).

After being introduced as an animal forage species, kudzu (Pueraria montana) escaped to invade forested areas in the southern United States. Kudzu is neither naturalized nor sold in California.

The ability to predict potential invasiveness is important both for species that have already been introduced to a region but are not yet invasive and for species that may be introduced through the horticultural industry in the future. In both cases, prediction of invasiveness before it occurs can, through collaborative efforts with the nursery industry, lead to voluntary restrictions in sales, preventing the potential for damage should the species escape cultivation.

Knowing that a plant is invasive in one region can give insight into whether it might be problematic in another region, particularly if the two regions have similar climates. For woody ornamental species, for example, being invasive elsewhere was the single best predictor of potential invasiveness in a new region of introduction (Reichard and Hamilton 1997). In addition, Caley and Kuhnert (2006) showed that four variables were most important for screening potential invasive plants: human dispersal, naturalized elsewhere, invasiveness elsewhere and a high degree of domestication. Two of these variables, human dispersal and high degree of domestication, are characteristics of horticultural species.

California is one of five Mediterranean climate regions in the world, along with the Mediterranean Basin of Europe and northern Africa, central Chile, the Cape Region of South Africa and western Australia. All these regions are characterized by a winter rainy season and a summer dry season and are likely to share invasive species due to their similar climates.

The primary objective of this study was to identify ornamental species at high risk of becoming newly invasive in California. To develop this list, we considered the single most important factor to be a species’ invasiveness in other areas of the world with a similar Mediterranean climate or in a state neighboring California. While we recognize that this list is not comprehensive, we believe that it provides a good starting point for subsequently conducting risk assessments that could reduce the threat of introducing new invasive ornamentals to the state. This approach might also help determine which naturalized species should be monitored to see if they will become truly invasive.

Identifying potential invaders

Invasive plant data were collected through online databases and published lists from other regions with Mediterranean climates. We also used established invasive plants reported from states neighboring California, including Arizona (Northam et al. 2005), Nevada (Nevada Department of Agriculture 2005) and Oregon (Oregon Department of Agriculture 2006). We included species on the California Noxious Weed List (CDFA 2007) as well as those that have been shown to invade wildlands (Cal-IPC 2013; personal communications with land managers in California).

Of the plants that have invaded other Mediterranean regions, we first removed species native to California and those already known to be invasive in wildland areas within the state. Then for each of the remaining plant species, we evaluated the Mediterranean-type region(s) invaded, location of origin, human uses (especially in horticulture) and whether the species was native, cultivated, naturalized or invasive in California (Baldwin et al. 2012; Cal-IPC 2013). For species already naturalized but not yet invasive in California, we determined the year they were first reported as naturalized based on the online Consortium of California Herbaria database (ucjeps.berkeley.edu/consortium/). In addition, we determined if plants are currently sold in the horticultural and ornamental trade in California using the Sunset Western Garden Book (Brenzel 2007) and the Plant Locator (Hill and Narizny 2004), a directory of nurseries stocking particular species. While these references do not include all of the species available by mail order or via the Internet, they represent plants most commonly available in nurseries.

Fanwort (Cabomba caroliniana) is an invasive aquatic weed in California that was introduced through the aquarium industry.

Which plants are likely threats?

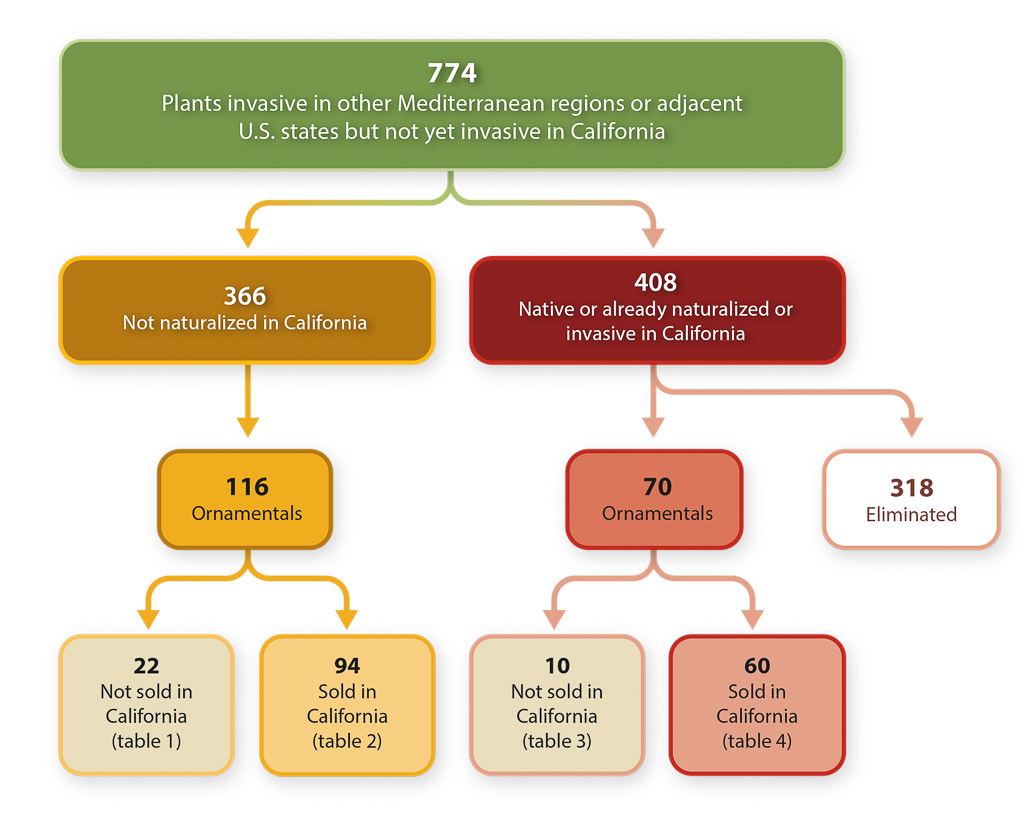

Based on our criteria, we found 774 plants listed as invasive in other Mediterranean regions or adjacent states (fig. 1). Of these, 366 (47%) are not naturalized in California and therefore fit our focus on potential new invaders. Of the remaining 408 species (53%), we eliminated 318 species that did not fit our focus on new invaders: they were either native to California (Baldwin et al. 2012) or already invasive in California (DiTomaso and Healy 2007), or had naturalized in the state before 1940 without becoming invasive (Consortium of California Herbaria 2008). This left us with 90 species that naturalized after 1940.

Fig. 1. Process used to determine the species with potential to become invasive in California through surveys of other Mediterranean climatic regions and adjacent U.S. states, with a focus on species sold as ornamentals. Tables 1 to 4 list these 186 species (22 + 94 + 10 + 60). The 318 eliminated species were eliminated because they are native to California, already invasive in California or have been naturalized in California since before 1940 without becoming invasive.

We assumed that species that naturalized before 1940 and that have not yet become invasive in California are unlikely to become invasive in the future. Many of the naturalized species have been present in the state for over a century, with 20 recorded in the 1860s and 144 recorded before 1900. While we believe that 70 years of naturalization without significant spread and harm is sufficient to consider a species as having low potential for invasion, this may not be true for all species. There may be some instances where longer lag periods — a length of time when a species is present in natural areas before beginning to spread and cause ecological harm — could occur prior to rapid expansion of a species. Furthermore, the movement of ornamental plants is facilitated by humans, thus increasing the opportunity for introduction to suitable habitats. In addition to possibly increasing the potential for invasion by introduced plants, this facilitation could also reduce the time between introduction and invasion.

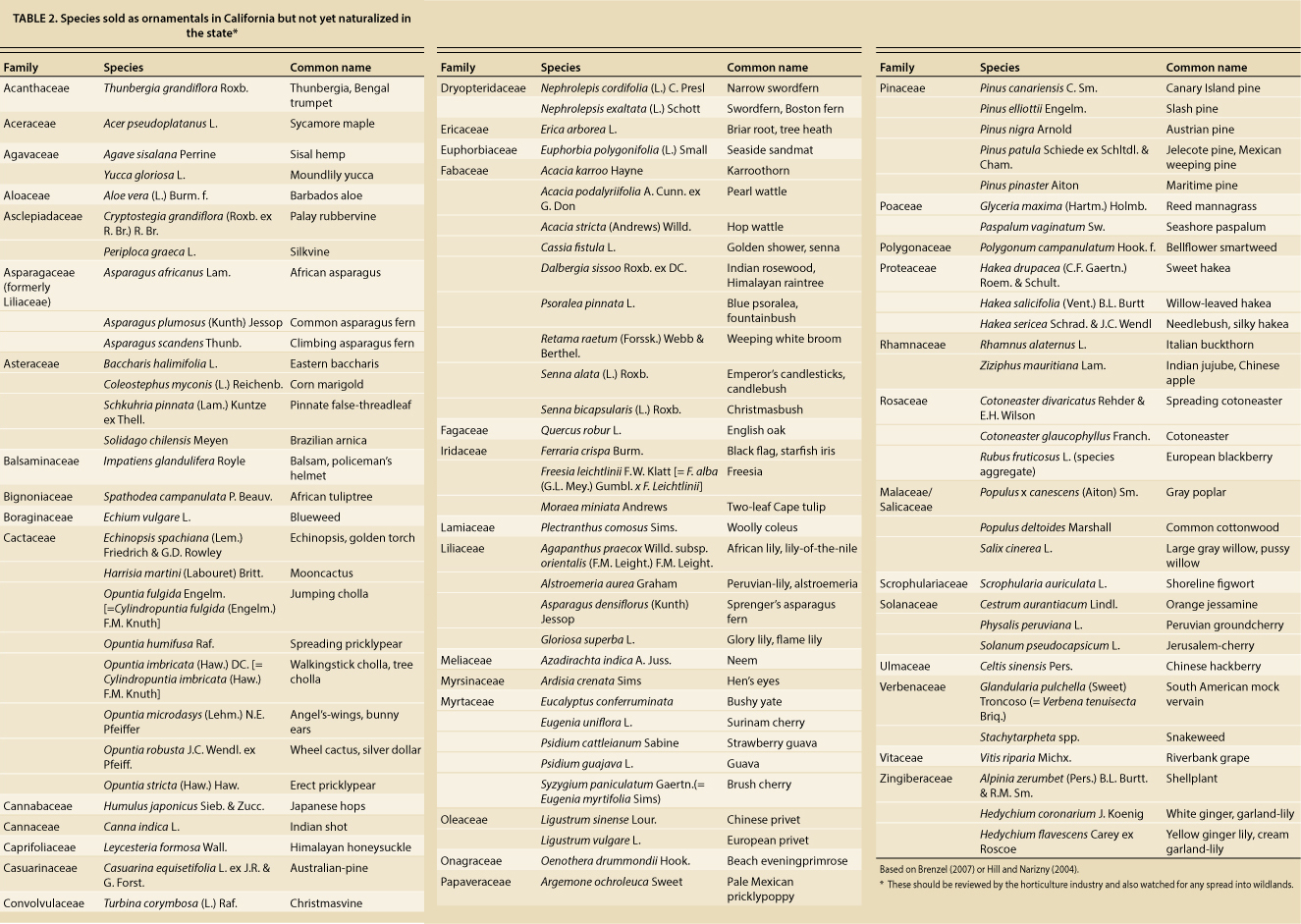

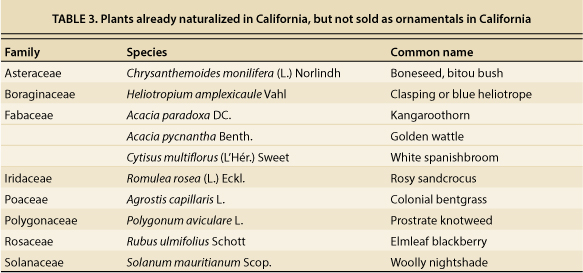

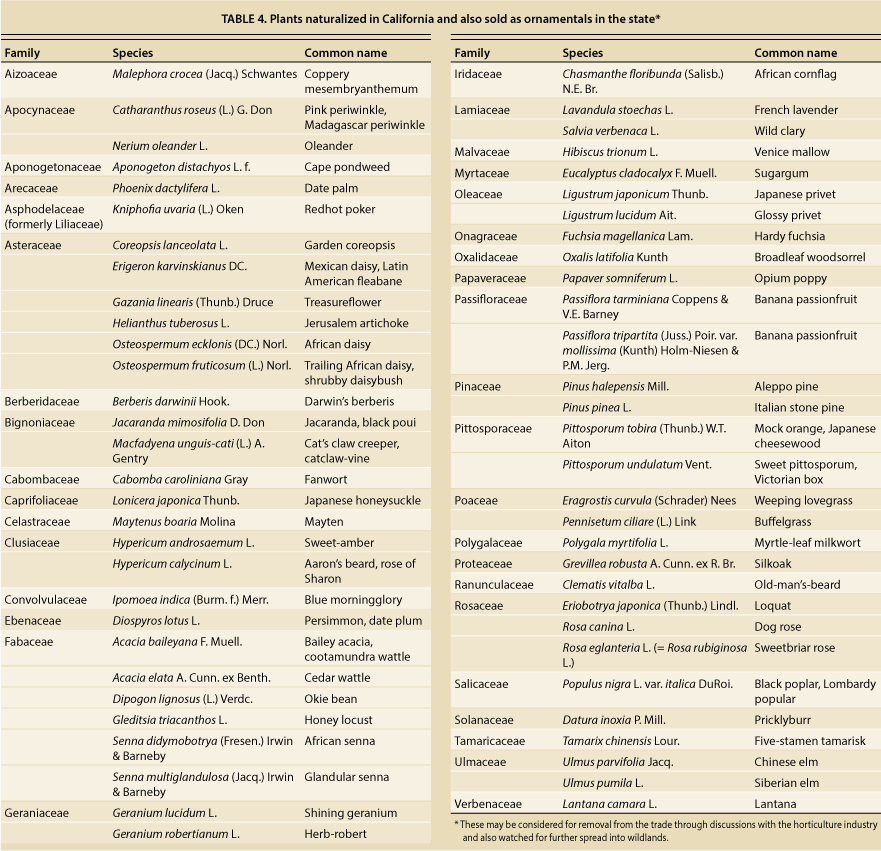

Next, we subdivided the 90 species that became naturalized after 1940 and the 366 species that are not naturalized in California based on whether they are sold as ornamentals. We also noted whether they are sold in California (fig. 1). Of the 90 naturalized species, 70 (78%) are currently sold as ornamentals somewhere in the world, with 60 (67%) sold in California. Of the 366 nonnaturalized species in California, only 32% (116 species) were ornamentals. The majority of these species (94, or 81%) are currently sold in California, while the other 22 are ornamentals not sold in the state. Thus, in total, we listed 186 species of ornamentals as the greatest concern for introduction and/or invasiveness to California through the horticultural pathway. This total includes both those species currently sold and those that could be sold in the future (tables 1 to 4).

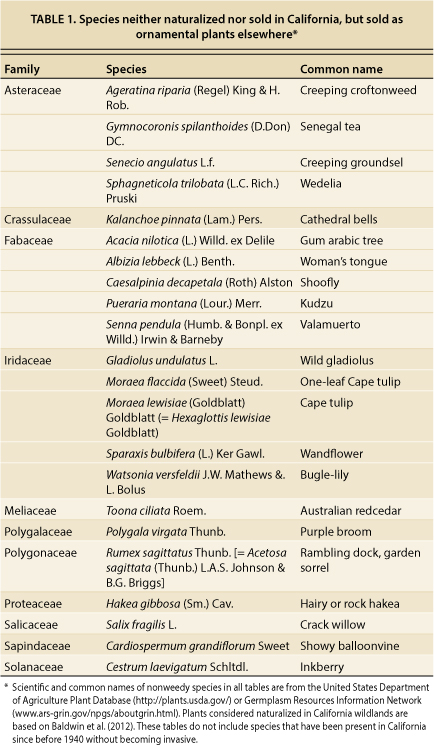

TABLE 1. Species neither naturalized nor sold in California, but sold as ornamental plants elsewhere*

This study, however, did not take into consideration the potential effects of climate change on habitat suitability and plant invasions within California. It is possible that warmer temperatures or modified precipitation patterns due to climate change will allow some currently noninvasive ornamentals to spread and become invasive. However, predictions of the spread of invasive plants in the western United States indicate that while some will likely spread, others may contract their ranges (Bradley et al. 2009). Thus, it was not possible to determine the impact of climate change on all the species evaluated in this study.

Rosy sandcrocus (Romulea rosea), a fairly new invasive species along the central coast of California, was introduced as a garden ornamental.

Management implications

To reduce the sale of invasive plants in California, environmental groups, scientists, government agencies and the horticulture industry are participating in the PlantRight partnership, a coalition that works with retail nurseries and growers on voluntary measures to reduce the sale of invasive plants and promote noninvasive alternatives (plantright.org); the authors serve on its steering committee. Specific guidelines or recommendations could be established for the high-risk species we identified in tables 1 to 4 to minimize future introduction, establishment and invasion. Cooperative efforts can discourage the introduction of ornamental plants in other regions that are neither naturalized nor sold in California (table 1), and these plants also could be included in a cautionary list that would require full prescreening risk assessment before introduction to the state. Plants that are not naturalized in California but that are sold here (table 2) should be reviewed by the nursery industry to reduce their sale and also watched for any spread into wildlands. In addition, noninvasive ornamentals that serve the same purpose in a landscape (same plant shape, same color flowers, etc.) should be promoted as alternative options. Species that are naturalized but not yet sold in California (table 3) should be restricted from sale, and land managers should watch for their further spread. Finally, species that are both naturalized and also sold in California (table 4) may be considered for removal from the trade and also watched by land managers for further spread into wildlands.

Species introduced as ornamentals or forage species that have escaped cultivation in California include, left, Mexican daisy (Erigeron karvinskianus), Japanese honeysuckle (Lonicera japonica), buffelgrass (Pennisetum ciliare) and African daisy (Osteospermum ecklonis). While these species are not yet major problems in the state, some have become more serious invasive plants in other regions of the country.

This list provides a good starting point for identifying plants, especially ornamental species, that are invasive in regions with similar climates to California and could become problematic here. However, additional steps are required to further understand the potential risk of invasion. In particular, a more detailed risk assessment should be conducted for each of the species we identified as being at high risk for future invasion. Several risk assessment protocols (e.g., DiTomaso et al. 2012; Koop et al. 2012; Reichard and Hamilton 1997) are available to prioritize the greatest potential threats to wildland systems. Implementing these preventative approaches and establishing an early detection program to eradicate incipient populations of these targeted species are far less costly than attempting to manage or contain large well-established populations of invasive plants.