All Issues

Immigration reform and California agriculture

Publication Information

California Agriculture 67(4):196-198. https://doi.org/10.3733/ca.v067n04p196

Published online October 01, 2013

NALT Keywords

Full text

Over half of the workers employed on U.S. and California farms are unauthorized. Congress is debating reforms that would increase enforcement against illegal migration, allow unauthorized immigrants in the United States to become legal immigrants and create new guest worker programs. The status quo means uncertainty for farmers worried about labor shortages, uncertainty for workers fearful of removal from the United States and uncertainty for communities with large numbers of mixed families (unauthorized parents with U.S. citizen children). This article summarizes the data and assesses the implications of the major reform proposals for California agriculture.

Immigration reform

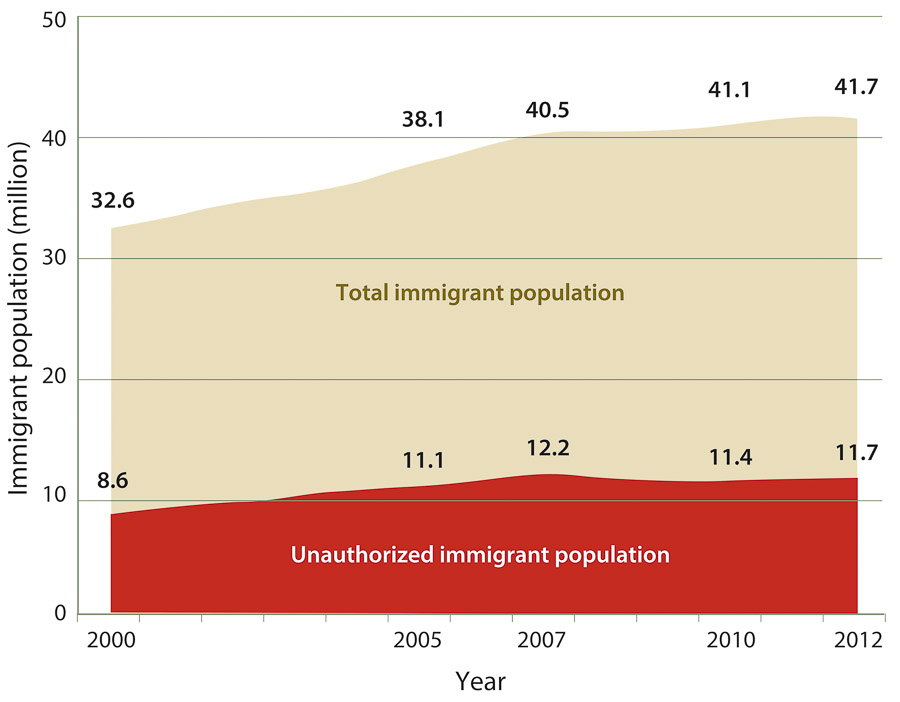

There were almost 42 million foreign-born U.S. residents in 2012, including almost 12 million (28%) who were not authorized to be in the United States. The number of immigrants born outside the United States continues to increase, but the number of unauthorized residents peaked at over 12 million in 2007 and fell to 11.4 million in 2010 before rising in 2012 (fig. 1).

The United States has been debating what to do about unauthorized immigrants for decades. In June 2013, the Senate approved the Border Security, Economic Opportunity, and Immigration Modernization Act (S 744) on a 68–32 vote, and President Obama endorsed S 744 as “largely consistent with the principles of common-sense reform I have proposed.” However, the House of Representatives has refused to consider S 744, opting instead for a piecemeal or step-by-step approach to immigration reform. The House Judiciary Committee approved four bills in June 2013, two dealing with the enforcement of immigration laws and two with new guest worker programs.

Senate: Enforcement and legalization

S 744 calls for more border and interior enforcement to deter illegal migration, legalization for most unauthorized immigrants in the United States and new guest programs to make it easier for employers to hire legal foreign workers temporarily. S 744 authorizes up to $46 billion in additional spending for a “border surge” to secure the 2,000-mile Mexico–United States border to prevent further illegal migration.

Currently, employers in some states and those with federal contracts must use E-Verify, the Internet-based system to which employers submit data on newly hired workers to determine if they are legally authorized to work in the United States. S 744 assumes that immigrants will be discouraged from coming to the United States if employers will not hire them, so it requires all employers to check new hires using the E-Verify system within 4 years. When hired, non–U.S. citizens would have to show employers a “biometric work authorization card” or immigrant visa that includes a photo stored in the E-Verify system, which makes it more difficult for unauthorized workers to borrow documents from legal workers.

After the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) submits a plan to secure the Mexico–United States border, unauthorized immigrants who were in the United States before December 31, 2011 could pay $500, any back taxes owed and application fees to obtain Registered Provisional Immigrant (RPI) status for 6 years, and this probationary status could be renewed after 6 years for another $500 fee. After a decade of RPI status, probationary immigrants could apply for normal legal immigrant status by showing they have worked (or were enrolled in school) and lived in the United States since registering. After 3 years as regular immigrants they could apply for U.S. citizenship.

Unauthorized farm workers would have a faster path to immigrant status under S 744. Those who performed at least 100 days or 575 hours of U.S. farm work in the 24 months ending December 31, 2012 could become RPIs with “blue cards” by paying an application fee and a $100 fine. Agricultural RPIs could become regular legal immigrants by doing at least 150 days of farm work a year for 3 years or 100 days of farm work a year in 5 years. The family members of RPIs could apply for immigrant visas when the farm worker does.

The United States now has three major guest worker programs. The H-1B program admits about 100,000 foreign workers a year with a college degree; about half of H-1B visa holders are Indians employed in information technology (IT) services. The H-2A program admits 60,000 foreign farm workers to fill seasonal farm jobs after the U.S. Department of Labor certifies farm employers as needing foreign workers; a sixth of these are in North Carolina. The H-2B program admits up to 66,000 foreign workers a year to fill seasonal nonfarm jobs in landscaping, resorts, hotels and reforestry; a sixth are in Texas.

Under S 744, the number of H-1B visas would double and there would be new guest worker programs for farm and nonfarm workers. There are several types of H-1B visas, and the number of the largest type would increase from the current 65,000 a year to 110,000, while the number for foreign workers who have earned advanced degrees from U.S. universities would increase from 20,000 to 25,000.

The current H-2A program for farm workers would be replaced by new W-3 and W-4 guest worker programs administered by the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA). The W-3 program would be like the current H-2A program and tie a foreign farm worker to a particular U.S. farm employer and job for up to 3 years. However, W-3 farm workers could work for another grower, known as a designated agricultural employer (DAE), after they completed their initial contracts if their visas allowed continued time in the United States. W-4 visa holders would need an initial job offer from a DAE to enter the United States, but could “float” from one DAE to another during the 3 years that their W-4 visas are valid.

The number of W-3 and W-4 visas would initially be capped at 112,333 a year, so that a maximum of 337,000 new guest workers could be in the United States at any one time. The minimum hourly wage for W-3 and W-4 crop workers would be $9.64 an hour across the United States in 2016, and this wage could be raised each year by 1.5% to 2.5%. S 744 requires farm employers to provide housing or a housing allowance of $1 to $2 an hour in most counties to both W-3 and W-4 visa holders, but not to U.S.-born farm workers.

A new W-2 visa program would admit more low-skilled nonfarm workers: up to 20,000 in the first year; 35,000 in the second year; 55,000 in the third year and 75,000 in the fourth year. No more than a third of W-2 visa holders could be employed in construction.

Where will U.S. employers get low-skilled W-visa workers? Mexico–United States migration has been declining, and more Mexicans returned to Mexico than were admitted in recent years. A century ago, many farm workers in western states were Chinese and Japanese. A combination of longer periods of U.S. employment permitted by S 744 and the opportunity for guest workers to bring family members with them to the United States may re-introduce more Asians to U.S. agriculture.

House: Enforcement and guest workers

The House Judiciary Committee approved four bills in June 2013 to increase enforcement against illegal migration and to modify guest worker programs for agriculture and IT. The Legal Workforce Act (HR 1772) would require all employers to use E-Verify to check the immigration status of employees within 2 years, sooner than the 4 years allowed by the Senate bill.

The Strengthen and Fortify Enforcement Act, or SAFE Act (HR 2278), would criminalize more activities by unauthorized immigrants to expedite their removal from the United States; increase the number of interior DHS immigration and customs enforcement agents by 5,000; and allow states and localities to enact and enforce immigration laws as long as penalties do not exceed federal penalties for the same offense. Unauthorized immigrants convicted of criminal gang membership, drunk driving, manslaughter, rape and failure to register as a sex offender could be removed more easily.

The Agricultural Guestworker Act, or AG Act (HR 1773), would replace the current H-2A program with a new H-2C program administered by USDA. Any farm employer, including dairy and food processing employers, could register with USDA to be designated as a registered agricultural employer (RAE) and petition to hire H-2C guest workers, including unauthorized workers currently in the country. However, H-2C visas would be issued only outside the United States, where workers would receive 18-month visas if they filled seasonal farm jobs and 36-month visas if they filled non-seasonal jobs. If their visas were still valid when the first job ended, H-2C workers could switch to another RAE, provided they were not unemployed in the United States more than 30 days. Employers would not have to pay the in-bound transportation expenses of H-2C workers or provide them with housing.

H-2C workers would have to be out of the United States at least a sixth of the time they were in the country, that is, for at least 3 months after being in the United States 18 months. To encourage guest workers to depart, 10% of the wages paid to H-2C workers would be held in an escrow account and paid with interest if claimed by returned workers at a U.S. embassy or consulate in their home countries.

The Supplying Knowledge-based Immigrants and Lifting Levels of STEM Visas (SKILLS) Act (HR 2131) would shift the 55,000 diversity immigrant visas currently available to citizens of countries that send few immigrants to the United States and make them available to foreign workers who earn advanced degrees from U.S. universities in STEM fields (science, technology, engineering and mathematics). SKILLS would raise the number of regular H-1B visas from 65,000 a year to 155,000 and double the number of H-1B visas for foreign workers with advanced degrees from U.S. universities to 40,000.

Implications for California

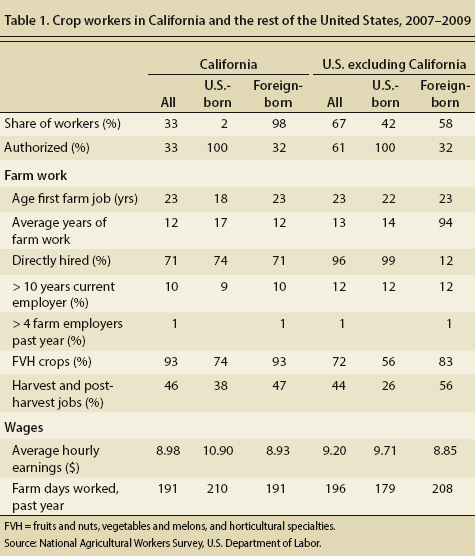

About 98% of the crop workers on California farms, and 58% of crop workers on farms outside California, were born abroad. Table 1 shows that the share of foreign-born crop workers who are unauthorized, 68%, is similar in California and the rest of the United States; however, since 98% of California's crop workers are foreign-born, California has a higher-than-average share of unauthorized workers than most other states.

There are no reliable data on the number of hired farm workers. The average employment of hired workers or the number of year-round equivalent jobs in U.S. agriculture is 1.2 million, including 400,000 in California. However, agricultural employment is seasonal, and there are an estimated two workers for each year-round equivalent job, suggesting 2.4 million U.S. farm workers and 800,000 in California.

According to the National Agricultural Workers Survey, foreign-born crop workers in California and the rest of the United States got their first farm jobs at age 23 and had done an average of 12 years of farm work when interviewed. About 71% of foreign-born workers were hired directly by growers in California, versus 94% in the rest of the United States. Very few crop workers in California and the rest of the country were with their current employer more than 10 years, and almost none had four or more employers in the past year.

Foreign-born workers are more likely to be working in so-called FVH crops than U.S.-born workers, that is, fruits and nuts, vegetables and melons, and horticultural specialties that include flowers and nursery products. Some 93% of California's foreign-born crop workers were employed in FVH crops, versus 74% of U.S.-born workers, a gap of 19%. In the rest of the United States, the gap was 27%. Foreign-born crop workers are more likely to fill harvest and post-harvest jobs than U.S.-born workers, and the gap was significantly larger outside California than in California.

California crop workers had lower average hourly earnings and fewer days of farm work in the past year than crop workers outside California. U.S.-born workers earned more than foreign-born workers, but the premium for U.S.-born workers was almost $2 an hour in California and less than $1 an hour in the rest of the United States. A full-time worker employed 5 days a week for 50 weeks has 250 days of work; the average crop worker had almost 200 days of farm work in the year before being interviewed.

If S 744 is enacted, most eligible unauthorized farm workers are expected to register and become legal workers; if the House bill is enacted, some unauthorized workers may be reluctant to leave the United States to receive legal re-entry visas as required. However, both the Senate and House bills are likely to give agriculture a more legal workforce comprised of perhaps a million currently unauthorized workers who register and become legal immigrants, and later an equivalent number of legal guest workers who replace them as they leave for nonfarm jobs. Both the Senate and House immigration reform proposals would allow guest workers to remain in the United States up to 36 months, which may encourage farm employers to seek workers farther afield (for example, in Asia).

Second, farm labor costs should be stable, since average hourly farm worker earnings are already above the minimum wage that must be paid to guest workers. Even if farm employers have to pay a housing allowance of up to $2 an hour to future guest workers, the $9.64 that must be paid to guest workers in 2016 plus a $2-an-hour housing allowance is less than the average hourly earnings of crop workers in California in 2012, $12.56 an hour.

Third, both the Senate and House bills should reduce uncertainty. However, the Senate bill may give growers in high-wage states such as California and Washington a competitive edge over those in lower-wage areas. Growers will be able to hire guest workers at $9.64 an hour, and wage increases would be limited to 2.5% a year, which should make it easier for California employers to plan investments and secure financing.

The agricultural provisions of the Senate bill were negotiated by farm worker advocates and farm employers, and both have said they will strongly resist efforts to change what they describe as a “delicately balanced compromise.” The House guest worker bill, on the other hand, is supported by many farm employers, including the California Poultry Federation and the North American Meat Association, but opposed by farm worker advocates such as the United Farm Workers. The Senate bill may stall due to opposition to legalization, but the House bill is unlikely to be enacted unless there is a severe farm labor shortage that threatens widespread crop losses and consumer price increases.

The most likely outcome of the immigration reform debate is a continuation of the status quo. This “broken immigration system” is not the first preference of any major actor, but it is the second-best solution for growers who get their work done more cheaply with unauthorized workers and for most unauthorized workers who prefer to live with uncertainty in the United States rather than leave. Until the logjam in Congress is broken, there is unlikely to be comprehensive immigration reform, and without a severe farm labor shortage, there is unlikely to be action on farm-specific immigration reforms.

Further Reading

Martin P. 2013. Immigration and farm labor: policy options and consequences. Am J Agr Econ 95(2):470-75. http://ajae.oxfordjournals.org/content/95/2/470.full

Rural Migration News. Quarterly. http://migration.ucdavis.edu/rmn/