All Issues

Limited-income seniors report multiple chronic diseases in quality-of-life study

Publication Information

California Agriculture 64(4):195-200. https://doi.org/10.3733/ca.v064n04p195

Published October 01, 2010

Abstract

The silver century is now! Seniors 65 and older are the fastest growing segment of the world's population, and in the United States the 85 and over age group is increasing at the highest rate. This study documents the chronic diseases reported by a diverse group (n = 377) of urban, limited-income seniors who attended UC Cooperative Extension Quality of Life education forums. The data suggests that their greatest educational need is learning how to integrate multiple concepts and complex research and technology into their personal lives. The data correlated disease conditions, diet and physical activity with age and ethnicity to show the magnitude of multiple diseases among them, identify perceived educational needs, and describe seniors’ expectations and preferred education and training delivery methods.

Full text

Good nutrition and a healthy lifestyle are often disconnected from concepts of wellness and “quality of life,” especially among the elderly.

Americans are living longer. The life expectancy at birth in California is currently 75.9 years for men and 80.7 for women (Lee and McConville 2007). The number of people 65 and older is expected to double in several decades, making up 20% of the U.S. population by 2030 (AOA 2003). Seniors over age 65 currently comprise almost 11% of California's population, and they are expected to double or triple in some counties by 2030. Seniors age 85 and older will increase at the fastest rate, over 150% in 38 counties (mostly northern and central California). The impact of this older group will become more evident as the first wave of baby boomers reaches age 85 in 2030 (CDA 2003).

At the same time, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) reports that chronic diseases such as heart disease, stroke, cancer and diabetes are among the most prevalent, costly and preventable of all health problems. Yet seven out of 10 Americans die each year from chronic “lifestyle” diseases that are extensions of what they do, or do not do, as they go about their daily living. Health-damaging behaviors such as tobacco use, lack of physical activity and poor nutrition are major contributors to the nation's leading killers, heart disease and cancer (US DHHS 2003). In California, these two diseases represent 54% of annual deaths, 29% and 25% respectively. Among adults 65 and over in California, the top-six chronic diseases diagnosed are hypertension (53.5%), arthritis (50%), heart disease (23.7%), cancer (17.3%), diabetes (14.8%) and asthma (10.3%) (Wallace et al. 2003).

One of the goals of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services guidelines for health promotion and disease prevention is to extend the years of “healthy life” — physically, mentally and socially (US DHHS 2000). In this context, proactive consumer education on health and wellness should promote positive conditions under which people can be healthy (IOM 2002). Client-friendly information and education are necessary to help elders address their quality-of-life issues more effectively. However, the complexity of disease processes, as well as health–related information, is often confusing for seniors and educators.

With the gradual rise in availability of ready-to-eat, high-calorie foods, food security issues, and families eating away from home more frequently, the benefits of good nutrition and healthy lifestyle seem to be disconnected from concepts of wellness, or “quality of life” issues. Likewise, obesity rates have risen rapidly in all age groups, as have other nutrition– and lifestyle-related diseases.

Wallace et al. (2003) notes that public health as a social good is concerned with equitable access to health care, with conditions conducive to high–quality care for all ages. Certainly, a well-informed aging populace can help respond to these concerns, and advance the notion that growing older and living longer does not necessarily mean that one must be in ill health.

Nutrition and wellness concerns

This study was designed to document the nutrition and wellness concerns among a diverse group of limited-income seniors, many with multiple chronic diseases, who participated in UC Cooperative Extension (UCCE) Quality of Life forums, which informed UCCE education and outreach programming for elderly Californians.

Data collection.

The Quality of Life interactive educational forums were initiated in 1993 and conducted by a UCCE nutrition, family and consumer sciences advisor in Alameda County. The goal was to increase the ability of seniors with limited incomes and/or low literacy to integrate science-based nutrition and wellness information into their lifestyles and ultimately improve the quality of their lives.

Self-assessment data was collected from 2003 to 2005 on a convenience sample of self-selected, multicultural seniors (n = 377) and 16 agency staff and volunteers. Seniors from 22 facilities serving limited-income seniors volunteered to complete the written, baseline self-assessments prior to the forums. The sites were senior meal programs, centers, clubs and low-income housing complexes in eight Alameda County cities.

Directors and coordinators of the programs distributed the assessments, assisted seniors who needed help completing the forms, set dates for the forums, and transmitted the assessments to the UCCE advisor-educator about 2 weeks prior to the 2.5-hour educational forums and focus group evaluations. The seniors listed their chronic conditions, lifestyle practices, physical activities and special diets. They reported whether they understood the physical effects of the chronic conditions they listed, their special diets, prescribed medications and perceived needs for nutrition and wellness education.

Data analysis.

The assessments were identified by numerical codes, which allowed the data to be treated confidentially. The responses were entered into an Excel database, and totaled; averages and standard deviations were computed and normalized. Computations from the raw data were compiled into two worksheets to show the distribution and prevalence of the responses. A third worksheet compiled the normalized data by dividing total responses for the questions and items by the population total (n = 377).

The normalized data expressed as percentages were used to describe and demonstrate relationships in selected areas, such as the intersections of age and ethnicity with diet, physical activity and chronic diseases. We calculated sample means, standard deviations, t-values, P values and ? values to determine levels of significance.

Forums and focus groups

The goal of the forums, usually conducted just before the noon meal, was to (1) process the concerns listed in the seniors’ assessments; (2) prioritize their nutrition and wellness education needs; and (3) learn more about how UCCE educators can meet their needs for information and education. We used several interactive, facilitative, learner–centered (LCE) techniques and principles, as described by the American Psychological Association (APA 2006). These included cognitive factors that influence knowledge construction and strategic thinking; and motivational, emotional, developmental and social factors that influence learning. We used these principles to help participants express their particular concerns, verbalize their needs in more detail, and identify their levels of knowledge and understanding for several diseases, including diabetes and hypertension. We used questions posed by the seniors themselves to demonstrate how to integrate, apply and expand their personal knowledge.

UC Cooperative Extension educators have offered quality-of-life workshops to seniors in order to help them integrate science-based information on nutrition and wellness into their lives. In focus groups, the seniors said they preferred client-centered education with a personal touch.

At the end of the forums, we conducted a 30- to 40-minute focus group evaluation to assess the clients’ satisfaction with the interactive teaching approach; clarify needs, and enhance knowledge and understanding; and allow seniors to express what they expected from UCCE educators. This client-centered process helped to highlight and prioritize mutual concerns and needs among the seniors, build confidence and personal motivation, promote positive wellness attitudes and encourage participation in more personal wellness activities.

Demographics and disease

The participants were 75% female and 25% male. They were multicultural: 54.9% white, 24.2% Asian/Pacific Islander, 15.4% black, 4.9% Latino and 0.5% American Indian.

The age groupings were 60 to 69 years (26.3%), 70 to 80 years (38.5%), over 80 years (19.4%) and age not reported (15.8%). All seniors in this sample reported at least one chronic condition; 22% reported two, 15.4% three, 8.2% four, 4.8% five and 5.0% six to seven.

The diseases reported were arthritis (40%), high blood pressure (38%), overweight (32%), high blood cholesterol (21%), stress (21%), heart disease/hardening of arteries (19%), gout (15%), diabetes (13%) and food allergies (12%).

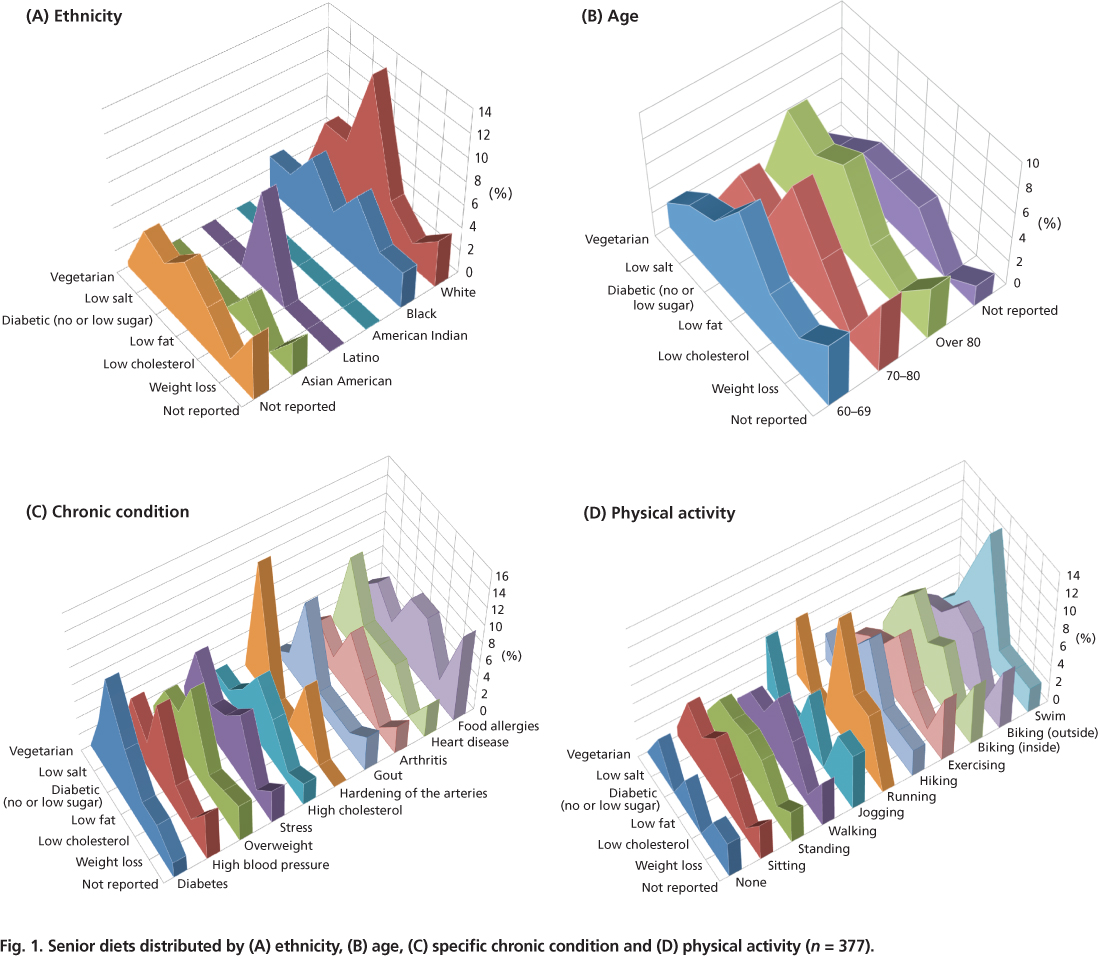

Fig. 1. Senior diets distributed by (A) ethnicity, (B) age, (C) specific chronic condition and (D) physical activity (n = 377).

We collected data on center staff (40 to 59 years, n = 16), but the number was too small to examine independently and was used for comparative purposes only.

Diet and exercise

About 26.5% (n = 100) of the group (n = 377) reported being on various diets, including low fat (34.2%), low/no salt (21.5%), diabetic and low sugar (20.3%), low cholesterol (19%), weight loss (7.6%), vegetarian (2.5%) and nonspecific, such as renal, gout or no red meat (10%).

Ethnicity.

Whites were significantly more likely to report low-fat and low–salt diets; blacks reported low-salt, low-cholesterol and weight-loss diets; Asian/Pacific Islanders reported only low-cholesterol diets; Latinos reported only low-fat diets; and American Indians reported no special diets (P > 0.05) (fig. 1A). Whites and blacks reported more low-sugar/diabetic and vegetarian diets.

Age.

Relatively few differences were found by age except for a significant increase in low-salt diets in later years (P > 0.05) (fig. 1B).

Diseases.

In general, vegetarians reported a significantly lower incidence of chronic conditions such as arthritis, allergies, stress and heart disease (P > 0.05) (fig. 1C). Those on low-salt diets reported significantly more heart disease, stress, high blood pressure, diabetes and allergies. The seniors on low-sugar/diabetic diets reported higher incidences of arthritis, diabetes and overweight. Those on low-fat diets reported higher incidences of overweight, high blood pressure and arthritis. And subjects on low-cholesterol diets reported higher incidences of overweight, stress, high cholesterol and allergies. Those on weight-loss diets reported higher incidences of overweight, diabetes, hardening of the arteries and allergies.

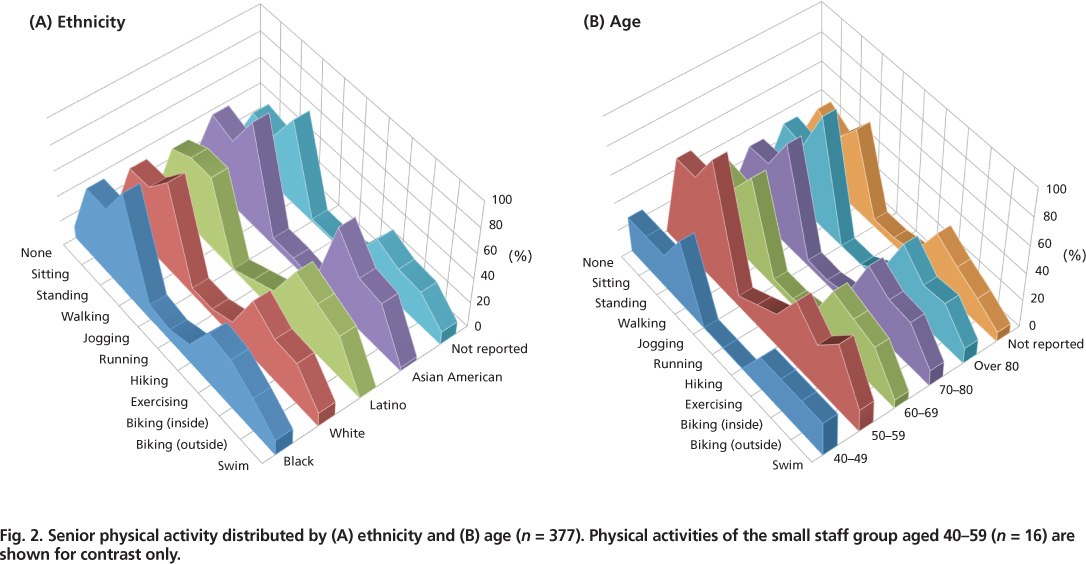

Fig. 2. Senior physical activity distributed by (A) ethnicity and (B) age (n = 377). Physical activities of the small staff group aged 40–59 (n = 16) are shown for contrast only.

Physical activity.

Seniors on different diets and those who reported no diets were equally as likely to report particular exercise activities. Vegetarians mostly swam, ran and jogged; low-salt dieters swam, rode stationary bikes inside and walked; diabetic dieters swam, walked, rode stationary bikes and did stand/sit exercises; low-fat dieters swam, hiked, ran and jogged; low-cholesterol dieters rode bikes inside and outdoors, jogged and stood/sat; and weight-loss dieters just walked. Seniors not reporting any diets tended to report more high-energy activities (P > 0.05) (fig. 1D).

Of the seniors surveyed who exercised, 5% said they ran or jogged regularly. Other exercises reported included walking (73%), biking indoors and outdoors (62%) and exercise classes and videos (42%).

Types of exercise.

Self-reported activities included walking (73%), exercising (including classes and videos) (42%), biking outside (30%), biking inside (32%), working around the house and yard (16%), swimming (10%), running/jogging (5%), going to the gym (4%) and yoga (2%). Physical activity distributed by ethnic group and age showed that all groups performed at about the same level irrespective of age or ethnicity (fig. 2).

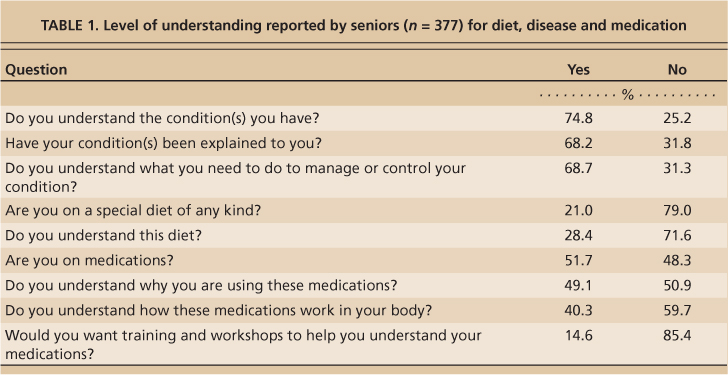

Health education needs

Over 51% of the survey participants said they were on medications but only 14.8% (n = 56) reported the names of the medications. Of the participants on medication, 48% were on one medication, 30% on two, 14% on three or four, and 8% on five or six. When asked if they understood why they were taking the medications, about 49.1% said “yes” and 50.9% said “no.” While 59.7% said they did not know how the medication worked in their body, only about 15% listed a need for training, a workshop or further explanation (table 1).

Some 71.6% said they understood the diets they were on, 74.8% said they understood their chronic conditions, 68.2% said their conditions had been explained to them, and 68.7% reported they understood what they needed to do to manage or control their condition.

Specific education and information needs concerned arthritis and gout (17%), low-fat/low-cholesterol diets and high blood pressure (about 16% each), diabetes (11%) and weight control (9%). Other areas (about 3% to 4% each) included health education, up-to-date food and nutrition, allergies, asthma, swollen ankles or legs, numbness in the legs, restless legs, dizziness and trouble walking, thyroid disorders, rapid weight loss, hypoglycemia, how to diet, medication and aging issues.

Processing complex information

Over 55% of the seniors reported multiple disease conditions. In the forums, some said the large volume of information encountered in their everyday lives often confused them. They expressed concerns about how difficult it is to make good use of information and to process confusing or conflicting recommendations. Participants were asked if they had difficulties reading or understanding information related to their disease conditions, medication or diets. Some with low literacy expressed low self-esteem and were offered extra peer-group support to participate in the interactive process. In general, these seniors were at higher risk of poor management of their chronic conditions because they were more likely not to make the best use of available information. Some had to contend not only with their personal concerns and conditions but also had responsibility for one or more family members with health concerns. Others struggled with adjusting lifestyles, making dietary changes and taking multiple medications prescribed to manage their conditions.

Literacy.

While many seniors from the baby-boomer era have high literacy levels and are computer savvy, millions of low-literacy and low-income seniors of the pre–baby boom era, similar to the ones in our forums and focus groups, remain at risk of poor health outcomes due to lack of information, misinformation, lack of understanding and/or misinterpretation. We found some seniors with literacy, vision, strength or memory concerns who also had multiple disease conditions with complicated ramifications, such as arthritis, diabetes and hypertension. This information challenge left some seniors timid and afraid to ask their health providers questions. Lacking sufficient understanding of their personal conditions, they said they needed an advocate to help them comprehend prescribed treatment and prevention plans. Without appreciation for the importance of their plans, they were less likely to make a firm commitment to follow through, whether the changes were lifestyle, dietary or medicinal.

Commitment.

We learned that when faced with the need to take multiple actions — such as improving their diets, adding activity to their lives and taking medications — some seniors complied with the easiest mandates and ignored the difficult ones; for example, they would “take the medicine, and eat what you want.” Some were less diligent with dietary and activity adjustments than needed. Some were also hoping for a quick result and became discouraged if they had to maintain changes over a period of time. If changes needed to become a way of life, or if they felt the adjustments were too limiting or difficult to fit into their daily lives, their commitment to the management plan waned.

Attitude.

Attitudinal responses suggested that some seniors tuned out and gave up. Their comments included, “What will be, will be,” “It runs in the family” and “I know someone with the same thing, and there is nothing they could do.” Some of these statements were expressions of frustration or feelings and attitudes resembling defeat, or they believed that they had no real control over the quality of their life experiences. Other seniors demonstrated good negotiation skills and assertiveness and were open to the possibilities of a healthier existence and better quality of life.

Seniors prefer the personal touch

Information presented to the low-income seniors that we studied needs to be not only science-based, but also client-friendly, useful and presented in an appealing format. The seniors’ stated preferences included: “We want people to talk to us, spend time with us”; “We have had enough of canned speeches”; “Speakers bring us what they want us to hear”; and “People often bring videos because they don't want to spend time to find out what we really want or need.” Their comments suggested the tenor of their concerns with traditional education and training delivery methods.

Health-damaging behaviors such as smoking, lack of exercise and poor nutrition are major factors contributing to heart disease and cancer, the nation's top two killers.

The baseline self-assessments and forum discussions showed that many seniors want more than a lecture to “pile on” more information and statistics. They want to have a meaningful dialogue, including: (1) participating in personal interaction, (2) feeling a personal touch, (3) having an exchange about questions and issues that matter to them and (4) spending personal time talking with the educator. One very elderly senior said, “Lady, whatever you do, don't bring me another video!” Their comments bear out the notion that in client-centered education people want educators to “tell me a story and put me in it” (Norris 2005).

Serving aging baby boomers

More than half of the state's seniors are at risk for chronic diseases related to nutrition and lifestyle, and the needs of aging baby boomers are expected to challenge health-care providers and UCCE nutrition and wellness educators for decades. Yet UCCE does not have a continuing framework for community education of California's aging baby boomers. The information that we collected from limited-income seniors in the self-assessments and focus groups suggests that their greatest educational need is learning to integrate multiple concepts and complex research, education, and information and technology into their personal lives.

UCCE educators have the opportunity to promote positive nutrition and wellness attitudes and behavioral changes to ensure a better quality of life for Californians in their later years. The challenge is to appreciate the needs and expectations of seniors and use educational approaches that they find most helpful to understand complex or conflicting information. In addition to a better quality of life, more-effective educational interventions can help reduce the costs of treating preventable diseases.

In light of the trend toward increased health awareness (Gorman 2007) such as eating healthier foods, seniors (like other age groups) can benefit from an enhanced understanding of how to make positive behavior changes. Educational obstacles can affect people of all ages, but chronic disease conditions among seniors, especially those with literacy and limited income or poverty, can exacerbate the problem (Weimer 1997, 1998). If the concept of healthy aging is to add life to years, not years to life, then nutrition and wellness can play a major role in enhancing the quality of life of California's elders.

Californians are living longer, but growing older does not necessarily mean that one must be in ill health.