All Issues

Regional identity can add value to agricultural products

Publication Information

California Agriculture 69(2):85-91. https://doi.org/10.3733/ca.v069n02p85

Published online April 01, 2015

NALT Keywords

Abstract

Regional identity creation is being recognized for its economic benefits and as a strategic resource for producer communities. A regional identity is not a brand; it is built through a complicated process of developing cohesion and sharing in the industry community and communicating outside the industry community to opinion-makers and consumers. The California fine wine industry has built successful regional identities and leveraged them to add value to their wines. As regional identities in the wine industry have strengthened, so has the industry, and a symbiotic relationship with other local value-added industries, such as tourism and hospitality, has emerged. Other agricultural producers can learn from the identity creation experiences in the wine industry. With the many challenges faced by California agriculture, identity formation may offer producers new ideas for adding value to their products and finding larger markets.

Full text

Identity can be an important factor for the success of regional economies. It can send strong signals of positive traits to consumers and the business community. In agriculture, many regions, such as Bordeaux, Champagne, Islay, Speyside, Parma and Tuscany, are identified with excellence and quality. A successful regional identity adds value to the products made there. Industries, often including tourism, grow in response to a region's identity. The region may also become a knowledge center, where producers share information and experts gather, which further contributes to its reputation of excellence and quality. As consumers, we are familiar with the regional identities of agricultural products, but there has been little research on the creation of regional identities. Here we draw upon our research (Beebe et al. 2012) on the creation of identity in the Paso Robles American Viticultural Area to interrogate the larger question of the dynamics of regional identity creation and how it can add value for agricultural producers.

The quintessential example of an agricultural industry that has a strong place identity is the California wine industry, in particular the Napa Valley industry. As a region, Napa Valley has firmly established itself as a world leader in wine. From its start, in partnership with UC Davis it has been at the forefront of innovation in both the technical sense (i.e., stainless steel fermenters, temperature-controlled tanks, etc.) and in the social sense of creating innovative networks of producers to share knowledge (Lapsley 1996; Peters 1984). The early pioneers, such as Louis M. Martini, Robert Mondavi and John Daniel Jr., who shaped Napa's industry created an industrial structure and an identity that in many ways codified what the U.S. wine industry would look like. Today, the U.S. wine industry is known for its varietal focus (as opposed to Europe's focus on regional blends), and it has shown the wine-drinking public that the United States can produce top-quality fine wines (Lapsley 1996).

Though the Napa Valley is the premier example, other winemaking regions, such as Paso Robles in San Luis Obispo County and the Alexander and Russian River Valleys in Sonoma County, are also developing recognizable identities. In all these areas, a sophisticated, high-value-added hospitality industry has emerged, which is synergistically contributing to strengthening the local identity.

Many winemaking regions in California, such as Alexander Valley in Sonoma County, are developing recognizable identities that add value to their wines.

Learning from Paso Robles

Winemaking in the Paso Robles region dates back to 1797, when Franciscan missionaries planted the Mission grape, but its long history of winemaking wasn't sufficient to earn it a regional identity for quality wines. Not until the 1970s did a group of winemakers and grape growers in Paso Robles begin the process of creating the identity for which it is known today. Growers in the Paso Robles area were selling their grapes into other regions for blending into top-tier wines and were confident the region could produce its own high-quality wines — and capture more of the value of their production — but they realized that this view of the region's wines was not validated by consumers or outside opinion-makers. To build a validated reputation and receive higher prices, they would have to organize and create an identity.

The first step was to secure federal government recognition as an American viticultural area (AVA), which would enable growers within the area to take actions that would have a collective benefit. A few visionary winemakers, winery owners and vineyard owners petitioned the federal government and in 1983 created an AVA that encompassed 614,000 acres (Federal Register 1983). The same year, the group held the first Paso Robles wine festival, which proved to be an impactful event because it convinced local growers that there was an opportunity to build a regional identity.

With relatively inexpensive land, an increasing level of coordinated organization and a growing reputation, the Paso Robles wine industry expanded rapidly. From 1986 to 1993, two new wineries on average opened each year. From 1994 to 2001, 11 new wineries on average opened each year. The owners came from a variety of backgrounds and brought new talent and financial resources. The expansion and attention being paid to the region attracted well-known winemakers from outside the region, which in turn attracted the attention of key opinion leaders, such as Robert Parker at The Wine Advocate.

In 1992, the emerging community became official with the formation of the Paso Robles Vintners and Growers Association (VGA). The association's goals were to educate and inform growers about new techniques and raise the reputation of local grapes in order to bring in higher prices for all growers. The VGA's goals were inward focused, but the VGA also presented a unified face to the outside.

As the reputation of Paso Robles wine improved and the region began receiving national media attention and a substantial increase in favorable wine ratings (Beebe et al. 2012), key local wine industry leaders recognized that the next step to strengthen the regional identity was to integrate into the group other businesses, such as those in the hospitality industry, whose success depended on the wine industry doing well. In 2005, the VGA changed its name to the Paso Robles Wine Country Alliance (WCA). It continued to include the growers and winemakers but now was open to hoteliers, restaurateurs and other wine-related tourism firms.

The WCA is effectively an expression of the Paso Robles identity, and it is responsible for broadcasting the key values of the Paso Robles identity. The WCA undertook marketing campaigns to publicize the AVA and pursued an aggressive place-based marketing campaign to promote Paso Robles as a fine wine region. The WCA is funded by members, and, among region-based wine groups in the United States, its budget is second in size only to that of the Napa Valley Vintners Association. This identity was not a random outcome, but rather was the result of a vision developed by the early entrepreneurs.

The creation and preservation of shared identities is not always easy. As the value of the Paso Robles identity increased, a group of winemakers located west of Highway 101, which bisects the region, decided that they would be better served with their own AVA, believing that their region produced higher-quality wines. This idea to secede from the larger group was serious because it threatened the value of the hard-won regional identity connected to the Paso Robles AVA label. As the threat grew, the local social networks that had been built earlier defused the controversy, and key Westside winemakers who had initially supported the division withdrew their support. They understood that a new AVA would cause confusion amongst consumers, and, more importantly, the identity that they had established might be perceived as incoherent and inauthentic by outsiders (Beebe et al. 2012). The social networks that had formed and the strength of the identity had become so strong that the notion among Westsiders that they could secure higher prices for their wines with a separate identity was outweighed.

Although most winemakers recognized the power of the Paso Robles identity, there was still a desire for wineries to be able to differentiate themselves within it, acknowledging the differences (e.g., microclimates, soil) that affect wine characteristics within the region. To achieve this, a coalition of winemakers and vineyard owners (emulating the Napa Valley model) successfully proposed to keep the Paso Robles AVA but create sub-AVAs, known as districts. A conjunctive labeling law was passed that stipulates a wine produced in a sub-AVA can feature that district's name but must also feature Paso Robles AVA in equal or greater significance (e.g., Paso Robles AVA, Adelaida District).

Creating regional identities

Like Paso Robles, many recognized regional identities began with a key leader or group of leaders initiating a process of organizing and working together to improve joint outcomes. The resulting regional identity is a collective good with shared ownership amongst the members. It cannot be managed as if it belonged to a single firm. Developing internal coherence and community commitment among members is vital for establishing and maintaining the identity; the process is about cooperating with others and establishing a shared vision for the region. The knowledge that is created and the value added to businesses develop the identity into a common resource available to members of the community; in this way, managing a regional identity is like managing a common natural resource, but the challenge is maintaining quality rather than not overusing the resource (Ostrom 2000).

Creating a geographical area with legally delineated boundaries defines those having a collective interest in the success of the area's identity. For wine, the AVA circumscribes the area and requires growers using the AVA label on their product to ensure 85% of the grape content is grown in the area. This is very different from French wine regions, in which boundaries as well as production practices are strictly regulated. For example, in Bordeaux, a red wine may use the AOC Bordeaux label only if it is made from Cabernet Sauvignon, Cabernet Franc, Carmenère, Merlot, Malbec or Petit Verdot grapes; the minimum sugar content must be 178 grams per liter; the vineyard must have a minimum of 2,000 vines per hectare and a maximum of 60,000 buds per hectare after pruning; and the resulting wine must be tasted and approved by an appointed committee (INAO 1936).

In the United States, instead of strict production rules, quality is maintained by social pressure, a collective interest in protecting the investment in the vineyards and wineries and increases in the value of the region's wines due to the perception of the AVA by outsiders. Members cannot impose direct sanctions on a member winery, but social pressure may be applied (e.g., not exchanging knowledge, not recommending the winery to visitors, criticizing certain wineries in the media or refusing to provide assistance in times of crisis).

These two approaches represent very different tactics: the French system honors tradition and cultural legacy — the classification system originated from an attempt to differentiate wine produced by aristocrats from wine made by commoners (Fourcade 2012) — while the U.S. system spurs innovation while protecting intellectual property rights (Lapsley and Sumner 2014). The remarkable result in the California fine wine AVAs is that even after an identity has been created there has not been a dilution of quality from free riders; rather, the identity dynamics have been so powerful that quality has increased.

Vineyards that belong to one of Sonoma County's 16 sub-AVAs display signs featuring the name and logo of their AVA.

Industry clusters

A regional cluster of businesses producing the same or similar products creates an advantageous environment for individual businesses. It also gains external significance beyond the fact of it being a collection of similar businesses in geographical proximity to one another. The significance is evident in the identity of Silicon Valley, not just a number of tech companies, or Hollywood, not just a number of filmmakers, or Napa Valley.

Scholars have observed that, in general, industry clusters have two key characteristics. The first is largely economic and refers to the horizontal structure of colocated competitors and vertical structure of proximate suppliers or customers. This arrangement ensures the constituent firms can attract skilled labor, and educational institutions are encouraged to produce specialized employees and to undertake relevant research.

The second key characteristic of clusters is the knowledge creation and network sharing that emerge. For example, while sitting in a café in the Napa Valley one is likely to hear discussion of wine and grape plant varieties, while in Silicon Valley the overheard discussion is likely to be on the newest Internet social media startup. These are indicators of the vitality of the information flow and, while untraded in a market, they have real economic value (Storper 1995).

Wineries are located in the Napa Valley for the climatic and physical attributes of the area, but knowledge sharing has significant economic value and attracts other, related industries. In industries with a high level of innovation-based value creation, having access to that knowledge means being on the cutting edge of new products and technology (Gertler 2003). In industries such as agriculture, where craft knowledge is important, effective institutions and mechanisms for sharing knowledge are important; in particular, the knowledge disseminated person to person is of great significance.

Much has been written about the formation and maturation of local industries into globally recognized clusters (Porter 1998). It is now accepted that the growth of these clusters changes the local environment physically, socially and economically (Porter 1998). It is remarkable how they become a magnet for talent, a foundation for the development of public good specialization and the basis of regional pride and cooperation.

Social and business interactions in an industry cluster do not simply generate a regional identity. Identity may emerge through social dialogue among interested local parties and be developed by strong social ties, but purposive action is involved; parties must decide on the key characteristics they want signaled by the shared identity. Regional identities are important because they “affect economic investments, including individuals’ decisions about where to locate their talents, entrepreneurs’ decisions about where to locate their organizations, and investors’ decisions about where to target financial resources” (Romanelli and Khessina 2005).

Brand versus identity

It is commonly believed that identity is synonymous with brand. However, several features differentiate the two. A brand is a form of intellectual property that has significance to consumers and, to at least a certain degree, can be created through advertising alone. Branding does not require the collective activities of the producer community, which is the source of the internal coherence necessary for identity creation. Most often, brand creation is a one-sided process of communicating to external audiences. Brands can certainly have a reputation for quality but when the brand is connected to a regional identity, it has a much greater ability to signal attributes about the region, both literal — producer of fine wines — and ephemeral — place to experience “the good life”— as can be found in the Napa Valley identity (Lapsley 1996). The Napa Valley name has much more meaning than simply producer of excellent wine.

Branding efforts absent this organic, community-derived effort have difficulty appearing authentic because they are perceived as simply the result of marketing. Some wineries have a number of brands, which they market differently. When they sell generic California wine, there is no strong identity associated with the wine and, not surprisingly, it has only weak meaning to consumers and garners a relatively low price in the market. In the traditional branding literature, a brand is often more or less placeless; it is not rooted to a geographic area. In contrast, the fact that the wine is from the Napa Valley AVA or the Alexander Valley AVA signals that the grapes are of high quality, and this has meaning to consumers.

In the United States, some agricultural regions have attempted to create regional brands that include a number of the area's products. Because such a brand is spread across items with diverse characteristics, uses and standards of quality, it is much harder to establish its unique value to consumers, and therefore it is more difficult to charge premium prices. For example, products from a large diverse agricultural county might include marmalade, lamb, peppers, firewood and Christmas trees; a regional brand on all these products delivers a diffuse message. In contrast, a regional industrial identity offers a focused message: for example, not just a wine, but a particular type of wine. In wine regions with well-established identities, members of the industry could recommend what to taste in order to understand the aspects of that region — if you want to taste the Napa Valley, get a cabernet sauvignon, the Russian River Valley, get a pinot noir.

The Russian River Valley Winegrowers group has an online database of its winegrape growers and has installed signs at all of its member vineyards.

Identity and reputation

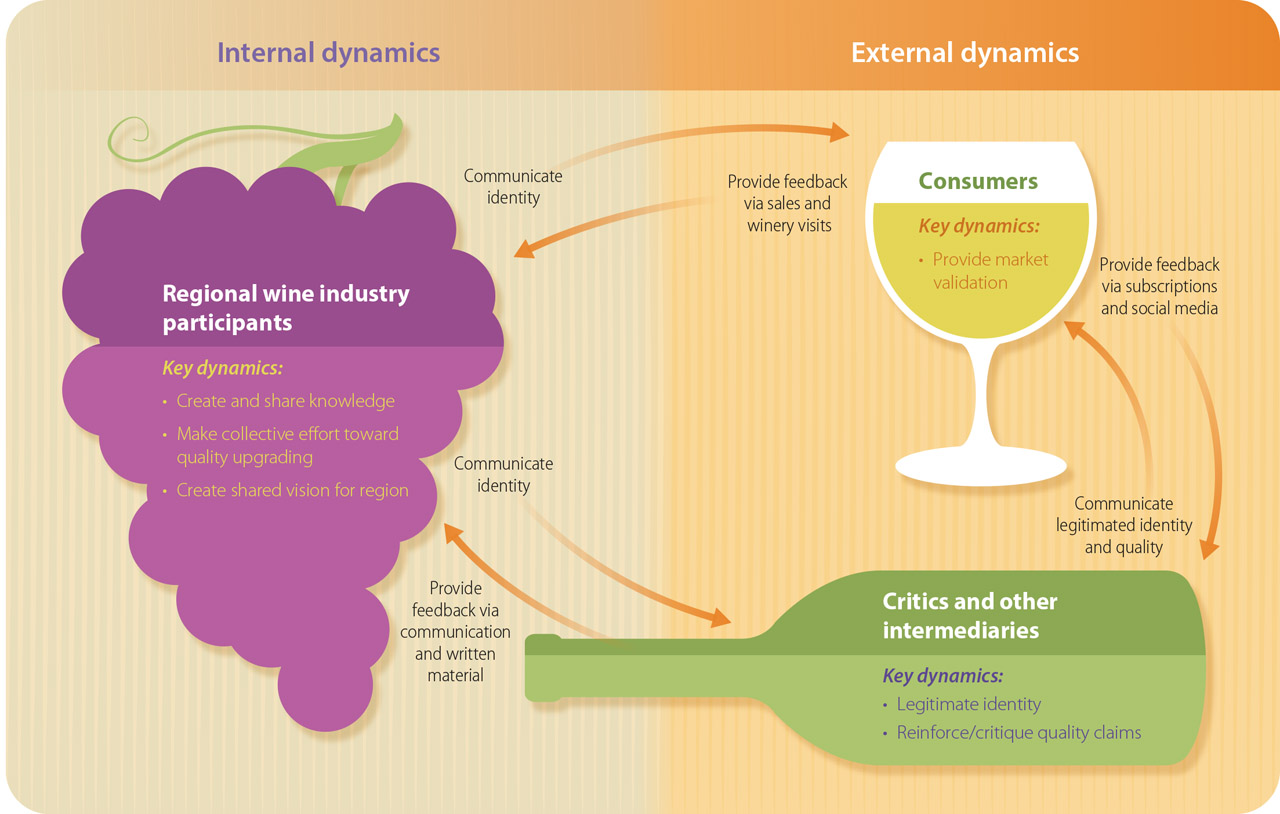

To be successful, an identity must be legitimated. Legitimacy accrues in a two-sided process: the identity creation and maintenance by the industry community, which is the internal side of the process; and validation of that identity by key intermediaries and critics, and eventually consumers, on the external side (fig. 1). The success of the identity, its accumulation of legitimacy, is dependent on the interactions between the sides. For example, a region may believe that it produces an excellent bottle of cabernet sauvignon, but if that belief is not shared by significant outsiders, such as wine critics, consumers will perceive the wine as overpriced. Or, if consumers recognize the regional identity, they confer value on the product; but if the product disappoints the consumer, then the regional identity also suffers.

Fig. 1. Identity formation in the wine industry. The first stage of identity creation is for regional wine industry participants to work together to create a shared vision of the region, which includes creating and sharing knowledge that can promote quality upgrading at the regional level. This identity is then communicated to critics and other key intermediaries, who legitimate the identity and quality claims in communications to consumers and back to wineries. Consumers provide validation to the regional wine industry through market sales and winery visits.

From this mutual dependence between internal and external parties flows one of the most powerful aspects of creating the identity, namely, the community interest in upgrading and investing in quality — further developing the knowledge, skills and technical ability to create higher-quality, higher-value products. In ideal cases, the dynamics between the internal and external parties enable the formation and growth of yet other activities, such as agritourism, that leverage the region's high-quality products as a springboard for further economic development.

In the wine industry, the Wine Spectator, Wine Enthusiast, Saveur, Food & Wine and restaurant sommeliers validate a regional identity by informing and educating consumers about it. For other agricultural producers aiming to create an identity, the cultivation, or establishment, of such intermediaries should be a central goal. Conversely, in areas where intermediaries for a product already exist, the product is ripe for identity creation. Intermediaries who can speak to large, dispersed consumer audiences provide an important validating function, more important than direct marketing.

Other strategies for increasing external visibility, and validation, include establishing events such as festivals. The Paso Robles Wine Festival was very effective at garnering external attention, especially in its largest primary market, Los Angeles. As the festival expanded each year, the external awareness of local wines increased. Local winemakers cultivated informal relationships with the Los Angeles entertainment industry, encouraging filmmakers to make films or television programs in the region. This media attention helped validate Paso Robles as a fine wine region with attractive tourist locations. Nearby, in the Santa Barbara area, filmmakers featured local wines in several films, including Sideways, which significantly increased sales for the region's wines.

U.S. versus European models

As mentioned previously, the U.S. and European models for creating and legitimizing agricultural identities differ. AVAs and French appellations, such as AOC Bordeaux, are geographical indications (GIs) formalized by the World Trade Organization in 1994 in the Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights. Both provide intellectual property rights to agricultural producers, protecting producers from fraudulent products made outside of the region or with nonconforming ingredients. GIs are a form of legitimization by governments; they signal that a group of producers has organized and created a petition for why their products are unique and should be protected. The presence of a GI may indicate that an agricultural identity exists for a region, but it does not guarantee that one exists. There has been much research on the potential for GIs to promote economic development and increase added-value, but the results are mixed and depend on the socio-political structure of the region (Parasecoli and Tasaki 2011), or as we argue, the presence of identity creation dynamics.

The strong identities associated with the GIs of Champagne, Parma and Bordeaux are built around the cultural heritage and traditions of the regions. In general, U.S. producers cannot draw upon deeply embedded regional cultural traditions. Napa Valley, the most famous wine region in the country, has been known for its distinctive wines only since the 1970s. Regional agricultural identity in the United States must be based instead on a pursuit of quality. This freedom from cultural tradition allows the development of innovative products, but producers must adhere to a perception of quality that is more rigorous and highly contested because the power to determine quality is spread out amongst a variety of actors throughout the supply chain as opposed to one small group of experts (Murdoch and Marsden 2000). How actors in the supply chain define quality and how they effectively create institutions to support their notion of quality is an area of research that we are currently pursuing.

Sonoma County

As recognition of the importance of identity increases, agricultural regions are trying to sort out what their identity should be. The identity formation process undertaken by one region may significantly differ from the process in other regions, depending on local social, geographical and product characteristics. Sonoma County has wrestled with how to build its identity. Should it follow Napa, which has an identity as a county (only a few areas of Napa County are not part of the Napa Valley AVA), or should it be like Paso Robles, which is part of San Luis Obispo County?

Sonoma County encompasses a large area with a mix of landscapes and climates, very different from the more homogeneous geography of Napa or Paso Robles, and it has 16 AVAs ranging in size and reputation. As in Paso Robles, producers enacted a conjunctive labeling law; all wine made in the county must have the words “Sonoma County” on the label. However, the law was much more contentious in Sonoma than in Paso Robles, and numerous growers, wineries and other industry participants are opposed to it.

The salient question is which identity will be legitimated and drive a collective upgrading process? Is there countywide sharing and solidarity, with strong ties binding the whole county together; or do the different regions in Sonoma County have their own character, industry organization, information flow patterns and cultures? From the external perspective, will key opinion-makers recognize the Sonoma County identity, or will they insist on referring to the various AVAs separately? Or alternatively, might there be a hierarchy of identities, with the individual AVA identity nestled within the county identity? The answers to these questions will determine whether conjunctive labeling is successful or obscures the current AVA identities.

Potential for other industries

Identity has long had a role in the wine industry. A strong regional identity could help expand the sales of other agricultural products, even globally. Many agricultural products in California are produced at a scale that far outstrips local demand; for example, the Bay Area foodshed, the growing area within a 100-mile radius of San Francisco, produces annually around 20 million tons of food, yet the local population consumes only 5.9 million tons (Thompson et al. 2008). Cultivating strong regional identities could upgrade, and add value to the region's products for export sales.

Outside of California, products such as coffee and tea have an identity component (e.g., Kona coffee, Darjeeling tea), though there has been little active effort to build strong identities for most of them. Scotch, Calvados and, more recently, Kentucky bourbon whiskies have such identities. Agricultural industries differ significantly from the wine and beverage industries, but regional leaders should still consider whether a regional industry identity could be built. While not all agricultural products can be transformed from commodity products into unique cultural goods that have other values embedded in them, thus making them more economically valuable, the task is to think creatively about possibilities and work collectively to bring them into existence.

Olive oil, hops, cheese.

The California olive oil industry is certainly ready for regional identity creation, and boutique olive oil tasting rooms in and around production areas, as well as in San Francisco, could communicate the qualities of the oils and reinforce the identity. Regional hops organizations could partner with the many California breweries emerging throughout the state. The artisan cheese industry in Northern California continues to grow and gain recognition; many opportunities exist for cheese tasting rooms and an organized effort to highlight regional cheese specialties. Above all, these regional industries must communicate to consumers and opinion-makers the internal cohesion and collective effort among the producers to upgrade quality.

Organic products.

Often mentioned is the possibility of developing regional identity on the basis of organic production, but most regions produce a large number of crops, making it hard to create a crisply focused identity. Further, the producers may see themselves almost entirely as competitors and thus be unwilling to share information and knowledge. Also, there may not be agreement on the goal — for example, to produce organic foods or high-quality foods? Does an organic tomato from the region have meaning that is resonant with consumers? Does an organic potato have a similar meaning? Using organic production as a way to get to higher quality might be a useful approach, but consumers’ associating organic with quality is different than their associating a region with quality. If another region focuses on organic production, these regions are then competing in the organic market instead of creating a market niche for each region.

Local products.

Locally produced food is one of the fastest-growing market segments within agriculture, but California produces more food than it can consume, so proximity of production is unlikely to work as the basis for an economically successful regional identity. Local production captures local dollars; whereas identity-laden products are focused on high-value markets external to the region. Also, for relatively durable goods, such as olive oil, distinctions of quality are hard to embed solely within notions of proximity and freshness.

Apples.

Apple Hill in El Dorado County has built some level of external recognition for its apple production, though mostly only in the Sacramento area. There has been limited evidence of — but also little research on — internal information sharing and cooperation among producers to improve quality. At this point, Apple Hill is a seasonal destination during the apple harvest; the production of less perishable apple-derived products extend the season and further add value. A significant opportunity exists for apple growers to take advantage of the growing interest in alternative alcoholic beverages by producing regionally distinct hard ciders or Calvados-like apple brandies. Some apple-growing regions, such as around New Berlin, Wisconsin, have focused a regional identity on antique apple varieties and connected the flavor profiles of the apples to the terroir of the land; these apples can be found in many of the high-end restaurants throughout the Midwest.

The agritourism industry in Apple Hill (El Dorado County), initially based on apple production, has expanded to include wineries and Christmas tree farms.

Adding value through identity

We have argued that a regional industry identity, though often not considered a significant economic variable, could, on the contrary, be of great significance for producers of distinct agricultural products. Developing identity is not a panacea for the difficulties of increasing income from agricultural products, but it has the potential to create new ideas for adding value. Improved communication and information sharing within the region could increase industry solidarity and, of particular importance for creating higher value, improve quality.

A regional identity may also benefit other industries and increase rural income. The Napa Valley has become one of the largest tourism destinations in the United States; Paso Robles also is developing an increasingly significant hospitality industry. Lastly, for producers increasingly pressured by low-cost imports, environmental demands and labor cost increases, identity development ideas can offer a basis for changing current income trajectories.