All Issues

The need for caregiver training is increasing as California ages

Publication Information

California Agriculture 64(4):201-207. https://doi.org/10.3733/ca.v064n04p201

Published October 01, 2010

Abstract

As the first baby boomers reach age 65 in 2011, California will face unprecedented growth in its aging population. At the same time, budget cuts threaten California's In-home Supportive Services (IHSS), which now assists seniors aging at home and the disabled. We conducted a cost analysis and compared caseload changes using IHSS raw data from 2005 and 2009. Results showed an across-the-board increase in caseload and cost for indigent in-home care in California, with significant variation from county to county. Large numbers of minimally trained IHSS caregivers, and family caregivers with little or no training, raise concerns about the quality of care that elders and the disabled receive, while highlighting the need to protect the health and well-being of caregivers themselves. UC Cooperative Extension can play a vital role in training undertrained and unskilled caregivers through applied research, curriculum design, education and evaluation, and proposing public policy options to help raise the competencies of caregivers.

Full text

As the baby boomers become senior citizens, the number of people needing assistance with the basic activities of daily living will rise.

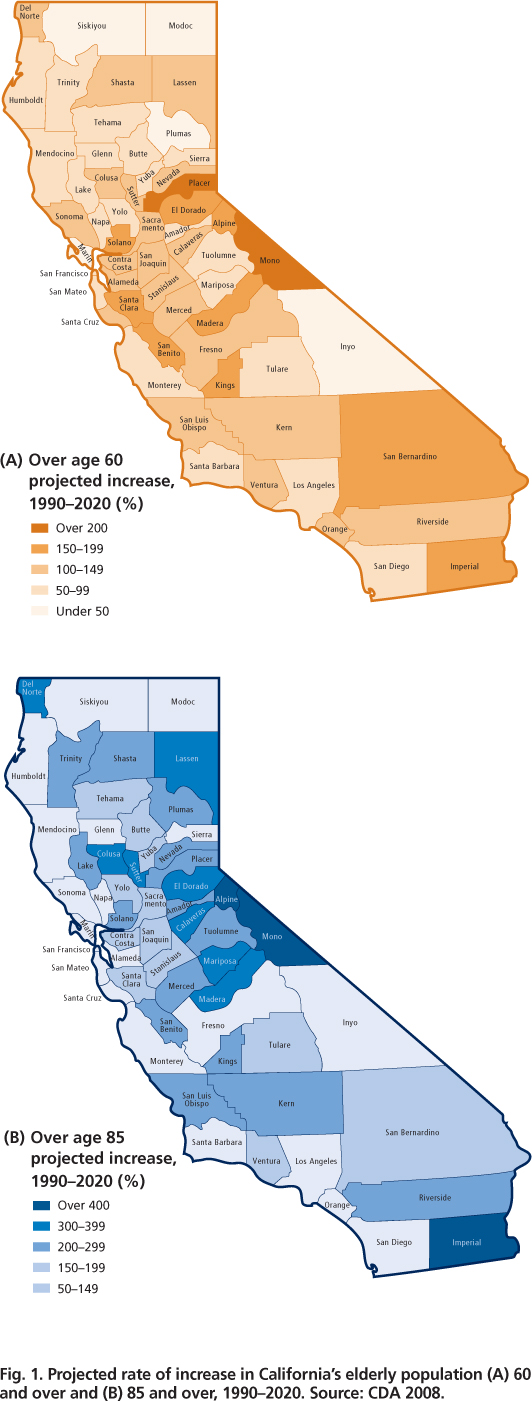

Advances in medical technology and improved health care have contributed to an increase in life expectancy from 47 years in 1900 to 72 years in 2001. In California, life expectancy at birth is currently 75.9 years for men and 80.7 for women (Lee and McConville 2007). The projected rate of increase in Californians over age 60 (fig. 1A) and age 85 (fig. 1B) is expected to rise across the state but at varying rates in different counties, and urban and rural areas. As California ages it will become more racially and ethnically diverse, with over 40% of baby boomers being ethnic minorities (black, Latino or Asian-American) and one-third born outside of the United States (Lee et al. 2003).

The aging baby boomers are changing the characteristics of the typical family unit. Their sheer numbers are expected to affect a myriad of social, family, financial and health issues. In a state report, former Assemblywoman Patty Berg, then chair of the California Assembly Committee on Aging and Long-Term Care, expressed concerns that the state is at a crossroads: “Whether aging Californians live in their own homes, receive in-home support, live with a relative [or in an] assisted-living, residential facility or a nursing home, one of the keys to their well-being is quality family caregiver support” (Berg 2006).

The risk of disease and disability increases with advancing age. Nationally and in California, 80% of elders over age 65 have one chronic condition and about 50% have at least two. In some California counties, chronic disease accounts for as much as 80% of the total disease burden (Prentice and Flores 2007). One study using a convenience sample of fixed-income seniors from 22 urban program sites in Alameda County (n = 377) reported that 55.4% experienced two or more chronic conditions, and about 10% had five to seven conditions ( see page 195 ). The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention expects chronic diseases to exact heavy health and economic burdens on older adults from long-term illness, diminished quality of life and major increases in health-care demands (CDC 2008).

More than 3 million older adults cannot perform the basic activities of daily living, such as bathing, shopping, dressing or eating (Prentice and Flores 2007). By one estimate, more than 1.5 million adults in California have physical or mental disabilities requiring ongoing assistance with day-to-day activities (Scharlach et al. 2001). Public health professionals are gravely concerned that the health-care workforce, including family caregivers, is not adequately prepared for the demands and emerging needs of America's aging population (Krisberg 2005).

Fig. 1. Projected rate of increase in California's elderly population (A) 60 and over and (B) 85 and over, 1990–2020. Source: CDA 2008.

A recent report by the California Legislative Analyst's Office found that about 83% of California In-Home Supportive Services (IHSS) cases are age 45 and over; 25% are 45 to 64 years old; 58% are over 65; and 25% are over age 90 (LAO 2010). California faces a shortage of trained professionals with the knowledge and skills to provide and operate quality caregiving programs and services for older adults (Berg 2004). The demands for unpaid family caregiver services, particularly among the “near-elderly” population aged 40 to 64, are expected to increase substantially (Lee et al. 2003).

The caregiver's role

The term “caregiver” refers to an individual who provides assistance to someone incapacitated to some degree, who needs help with the activities of daily living such as dressing, eating, shopping and toileting. Caregivers are formal and paid, or informal and unpaid. Formal caregivers can be associated with a service system or may be hired as independent care providers. Most often, informal caregivers are unpaid family members, friends, neighbors and other individuals from organizations such as churches.

Quality in-home care involves a range of fundamental skills such as reliability, punctuality, confidentiality, respecting others in the work environment, administrative tasks, physical care and medically related skills (Barnes et al. 2005). The most common caregiver responsibilities can be categorized as personal care, emotional support, financial assistance and linking to formal care providers, with an array of time-consuming tasks in each category.

Public and private institutions and agencies provide skilled, certified in-home caregivers and skilled independent workers. IHSS, a California Public Authorities agency, was mandated by AB1682 in 1999. IHSS screens and registers caregivers, provides orientation and serves as their employer of record. It is the largest publicly funded caregiver service in California for the blind, aged or disabled requiring nonmedical personal care. It pays for in-home care while impoverished, low-income seniors and disabled or incapacitated persons remain safely in their homes. The program is intended as an alternative to nursing homes and board-and-care facilities, or to limit the time that clients need to be institutionalized. However, the majority of about 400,000 IHSS registry caregivers are either not certificated or are undertrained. The California Public Authorities mandates some training — the minimum requirement is a 30-minute video focused on how the IHSS program works, elder abuse and fraud.

A large body of research has investigated the impact of caregiver responsibilities on family members, particularly families who care for members with mental illness. An estimated 4 million or more families nationally care for members with dementia, and most have no formal training. In general, informal family caregivers are more likely to care for someone with emotional problems, dementia/memory problems, behavioral problems, stroke or paralysis.

Many caregivers spend 4 to 7 years, or up to 15 to 20 years, doing a job that is stress-filled, overwhelming and isolating (Zarit 2010). Caregivers often face a variety of physical, emotional and financial stressors alone, which increases the probability that they themselves will suffer from breakdown, neglect and abuse. Over time caregivers suffer mental and emotional drain, feelings of defeat, anxiety, resentment, anger and stress (Noh and Turner 1987; Miller et al. 1990). The burden of caring for a schizophrenic has been associated with infectious disease episodes (Dyck et al. 1999). Caregivers reported twice as many gingival (gum-related) symptoms as noncaregivers (Vitaliano et al. 2005) and other metabolic changes (Vitaliano et al. 1996).

About 400,000 caregivers are registered with California In-Home Supportive Services (IHSS), an agency that screens caregivers, provides orientation and serves as their employer of record. However, training requirements are minimal.

The stresses associated with caring for an elderly patient at home can also prematurely age the immune system, placing caregivers at greater risk for developing or aggravating a number of age-related diseases. Researchers tested blood samples over a 6-year period from a group of caregivers working with Alzheimer's patients. They measured the levels of a naturally produced immune chemical, interleukin-6 (IL-6), which increases with age; high levels are a known risk factor for illnesses such as diabetes, depression, atherosclerosis, rheumatoid arthritis and some cancers. Test results showed that the blood levels of IL-6 increased fourfold among caregivers compared to a control group (Kiecolt-Glaser et al. 1987).

Research points to the need for more caregiver training and physical, emotional and financial support, for both formal and informal workers. Caregivers often suffer under enormous demands, with greater burdens placed on those caring for people with complex chronic illnesses (Family Caregiver Alliance 2008). California caregivers experiencing the highest levels of financial hardship, physical strain and emotional stress are more likely to be female, Latino, low income and in poor health themselves (Scharlach, Giunta, et al. 2003). The physical and emotional stress and strain over time, without relief, can take a toll on the caregiver and in some cases elders may suffer negative consequences. One of the main topics in the 30-minute IHSS orientation video is elder abuse. Thousands of cases of elder abuse and fraud are reported for both formal and informal caregiver services (Bailey and Paul 2008).

Pay and training needs

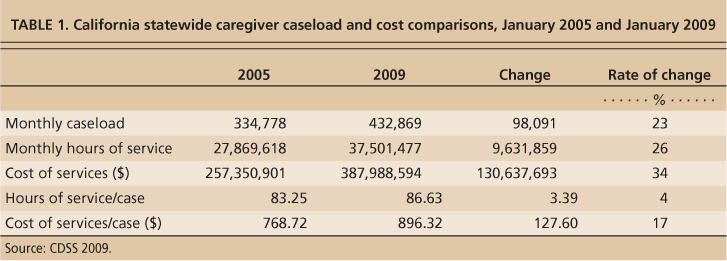

We conducted a cost analysis using raw data from the California IHSS database for January 2005 and January 2009. We calculated rates of increase in caseload, cost per case and unit cost of services, and compared county-by-county caseloads and costs. Demographics and needs data were derived from U.S. Census annual population estimates, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Administration on Aging, UC Center for the Advanced Study of Economics and Demography, UCLA School of Public Policy, California Legislative Analyst's Office (LAO), Sacramento County's UC Cooperative Extension (UCCE) caregiver research and training program, and Alameda County's assessment of the quality-of-life education needs of limited-income seniors ( see page 195 ).

Caseload, hours and unit costs.

IHSS has been one of the fastest-growing California programs in recent years. Prior to budget cuts, annual funding was estimated at $5.42 billion dollars in 2009 (Halper 2009), and in January 2010 the LAO estimated a yearly cost of $5.5 billion. In August 2010, the number of Californians receiving care was reported at 416,000; the number of caregivers employed, as estimated by disability advocates, was 800,000; and the cost of the program was reported as $5.7 billion. Our calculations showed that the caseload for IHSS caregivers grew about 29.3% over 4 years from 334,778 to 432,869 cases (table 1).

The increase in monthly caseloads ranged from 62% to 74% in two small counties (El Dorado and Placer) and one large county (Santa Clara), to a decline in three very small counties (Amador, Colusa, Trinity), one medium (Stanislaus) and one large (San Bernardino). We calculated that IHSS spent an estimated $387,988,594 for registry caregivers in January 2009, up 16.6% from the cost for January 2005. The rise in cost was due in part to increased caseloads, hours per caseload and unit cost of services (table 1). Our calculations of cost per hour of service delivered in January 2009 ranged from a high of $13.64 in San Francisco to a low of $7.87 in Ventura County. The hourly rate of pay in rural areas was generally lower than in urban centers (for detailed county cost analysis, see http://groups.ucanr.org/elderly/index.cfm ).

TABLE 1. California statewide caregiver caseload and cost comparisons, January 2005 and January 2009

Halper (2009) estimated that the IHSS cost of services per county ranged from $8.00 to $14.68 per hour. A survey by California Public Authorities in February 2010 reported that hourly caregiver wages in counties ranged from $8.00 to $11.55, and the cost per hour in August 2010 was between $9.00 and $11.00 (Oakley 2010).

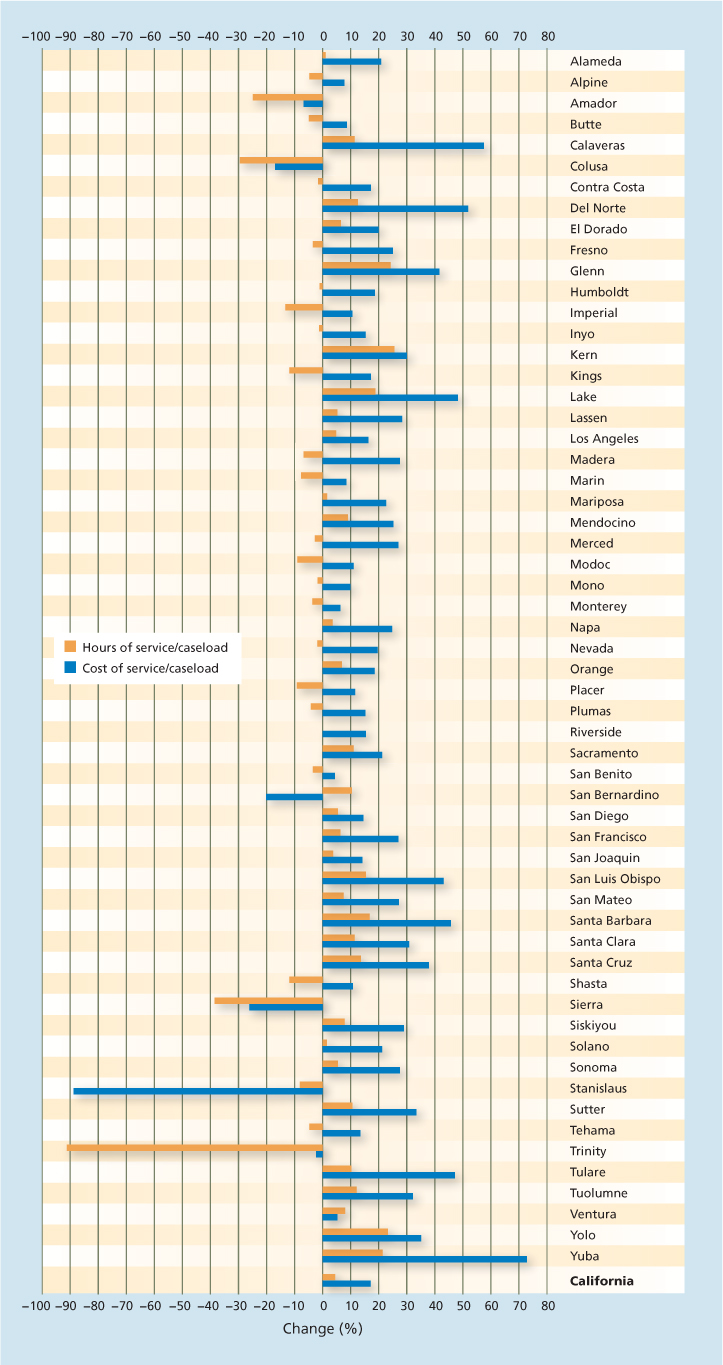

Fig. 2. Comparison of changes in monthly hours of service per case and cost of services per hour for California counties between January 2005 and January 2009. Source: CDSS 2009.

When we calculated the changes in unit cost of services by county for January 2005 and January 2009, we found that the IHSS registry caregiver data did not show any particular regional growth trends over the 4 years, either by size of monthly caseload or geographical location. Three counties grew over 60%; eight from 40% to 50%; nine from 30% to 39%; 11 from 20% to 29%; eight from 10% to 19%; and nine from 1% to 9%. Four counties showed essentially no growth, and six small counties with 40 to 1,700 cases showed declines from ?0.81% to ?12% (fig. 2).

The county highs for the average change in cost of services delivered per case were 72.66% (Yuba), 55.75% (Calaveras) and 52.08% (Del Norte). Changes in other counties ranged from 40% to 48% in four, 30% to 39% in six, 20% to 29% in 15, 10% to 19% in 17 and 1% to 9% in six counties. A decline was noted in six counties, Stanislaus (–89.12%), Sierra (–26.33%), San Bernardino (–20.35%), Colusa (?16.93%), Amador (–6.73%) and Trinity (–2.28%).

When California's IHSS program is examined as a potential cost saver, it has strengths and weaknesses. The LAO report suggests that the program may not be cost-effective when state and county costs are combined, but it is successful if one evaluates its potential to increase the quality of life of individuals (LAO 2010).

Education and training needs.

Research clearly points to the need for increasing the knowledge and skills of large numbers of undertrained caregivers in California (Scharlach, Sirotnik, et al. 2003; Barrett et al. 2005; Scharlach et al. 2006; Bailey and Paul 2008). Some public and private agencies and institutions provide skilled nursing and related care, but given their minimal training and orientation requirements most IHSS registry caregivers are undertrained. We collaborated in 2008 and 2009 with the training and outreach coordinator for IHSS in Alameda County to conduct food safety training for caregivers. The coordinator reported that budget cuts had forced many counties to stop providing any training beyond the minimum 30-minute video.

Formal/paid caregivers

A survey conducted in 2000–2001 of formal/paid caregivers (certified nurse assistant [CNA] and IHSS registry caregivers) provide insight into the training levels, working conditions, benefits and makeup of in-home caregivers in California (Ong et al. 2002).

Noncredentialed.

IHSS providers surveyed were mostly female (88.3%). Over half were relatives of the people that they cared for, and one-third had been an IHSS provider for five or more years.

Credentialed.

About 32% of those surveyed were CNAs; 35% were home health, home care and personal aides; and about 30% of CNAs also had a home health aide (HHA) certificate.

CNAs must complete 50 hours of theory training and 100 hours of supervised clinical training; pass a state test; know emergency procedures; be CPR-certified; and complete 48 hours of continuing education every 24 months. For HHAs, some states require CNA credentials, additional training and passage of a state exam. HHA tasks include giving medications, feeding patients, checking vital signs and assisting with errands and chores.

Employment.

Over 60% of HHAs and personal home-care aides, and over 30% of nurse aides, were part-time or temporary workers.

Working conditions.

About 25% of CNAs received welfare at some time from 1995 to 2000; 10% received welfare in 2000; and the proportion of welfare-eligible IHSS providers was 24%.

Benefits.

Job benefits were available only to full-time caregivers.

Job mobility.

About 5% to 12% of CNAs/HHAs trained to become licensed vocational nurses.

Unpaid family caregivers

Informal/family caregivers are unpaid individuals such as family members, friends and neighbors who provide care without compensation. A random telephone survey in 1996 of California households estimated that one in six (16.7%) with a telephone had at least one family caregiver — about the same rate found in a 1997 national telephone survey (17%) (Scharlach, Sirotnik, et al. 2003). Over 4 million unpaid family caregivers in California provide services worth about $45 billion annually, if estimated at $10.37 per hour. The number of family caregivers nationwide is over 65 million, and one-third are male (Sheehy 2010). More than 10 years ago, it was estimated that family caregivers provided the equivalent of $196 billion in free care annually (Arno et al. 1999).

The majority (61%) of family caregivers in the 1996 California survey were white, and the rest were Latino (25%), black (6%) and Asian/Pacific Islander (5%). The average age was 51 years; 75% were women; and 60% were married. Most (86%) were U.S. born, and 69% graduated from high school and 35% had college or some postgraduate education. Of those who provided incomes, 60% made over $30,000 and 36% more than $50,000 (Scharlach, Sirotnik, et al. 2003).

Training considerations

A large body of research shows that stress associated with caregiver duties may have negative impacts on their physical and emotional well-being, creating new risk factors for disease among caregivers themselves. The use of untrained workers in roles that potentially affect the quality of life of frail elders and disabled persons poses concerns for the caregivers as well as California's public policymakers, planners and service administrators.

More than 4 million unpaid caregivers provide an estimated $45 billion in services annually. Many take care of family members at home with little support or training.

In 2003, when considerably more training funds were available, IHSS in Sacramento County contracted with UCCE to provide 150 hours of training annually for its registry caregivers. In the absence of a training curriculum, UCCE Sacramento developed lesson plans based on assessment data from about 1,000 caregivers. Over a 6-year period, at least 600 IHSS caregivers were trained in basic care skills, including bowel and bladder care, skin care, diabetes care, infection control, dementia/memory loss, fall prevention, self-neglect, food safety, cancer, hypertension, heart attacks and job skills. New subject areas were added based on needs expressed by the caregivers.

Evaluations conducted on knowledge gained, ability and willingness to use information, program effectiveness and caregiver satisfaction with the training were uniformly positive. The results were presented at local, state and national professional meetings, posted on UC Delivers (a Web site of stories demonstrating how UC delivers to the citizens of California) and published in peer-reviewed journals (Barrett and Song 2003; Barrett et al. 2005). Funding for the project was discontinued in 2009, but long-range goals to develop, refine and standardize basic nutrition and wellness curricula for in-home caregivers statewide remain a priority among UCCE's human resources professionals. UCCE can play an integral role in framing educational solutions to increase the competencies of undertrained IHSS and family caregivers.

More research is needed to pilot and refine specific tools and methodologies for instruction, appropriate educational materials, and evaluation tools and methods. UCCE Sacramento County began important work on a basic caregiver-training curriculum, and at least five counties have trained caregivers on safe food-handling practices (Barrett and Song 2003; Barrett et al. 2005; Barrett and Blackburn 2009; Blackburn et al. 2009).

Human resources priorities

UC can make further contributions to the body of research on appropriate curricula, evaluate outcomes and impacts, and determine effective educational approaches and practices to train a diverse group of undertrained caregivers. The education and training needs of in-home caregivers were identified as a priority area during the 2008 ANR Human Resources Nutrition Update. Members of several ANR workgroups (Aging, Food Safety and Health Promotion) have conducted trainings with IHSS caregivers, developed and are pilot-testing curricula appropriate for caregivers, and are exploring possible funding sources for this work.

The University can work with policymakers, public administrators, service providers and caregivers to promote the need for a statewide strategy to upgrade the basic skills of undertrained caregivers. The expected impact is to increase the competencies of diverse groups of undertrained caregivers, enhance the quality and safety of care delivered to elderly and other disabled persons in California, and protect the well-being of caregivers themselves.