All Issues

UC after-school programs reach inner-city kids

Publication Information

California Agriculture 50(2):4-5.

Published March 01, 1996

PDF | Citation | Permissions

Full text

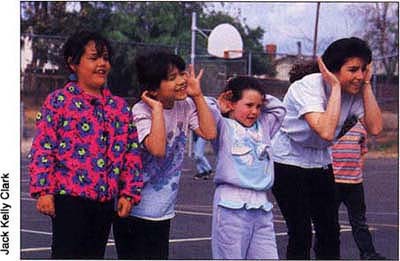

A public housing project in West Oakland may seem an unlikely place for 4-H — a program long associated with rural youth. But that is the site of the 4-H After School Activity Program (ASAP), a UC Cooperative Extension program designed to meet the after-school needs of urban youth.

Since its opening Feb. 6, the 4-H ASAP has offered children living in Oakland Housing Authority's Peralta Villa a chance to participate in an embryology project (hatching baby chicks and mealworms), as well as making a video simulating a newscast, in which participants could choose to play news anchor, reporter or interview subject.

Although after-school embryology projects may not directly alleviate poverty, gang violence, child abuse or child neglect, 4-H ASAP does provide inner-city children with a safe environment and educational enrichment that may help them to improve their lives.

Children in the Oakland 4-H ASAP, ranging in age from 7 to 13, live in an environment where unemployment is estimated to hover around 22%, and 90% of children are on welfare, according to a recent report in the San Francisco Examiner. They are part of an increasing cadre of California children considered “at risk” because of poverty, abuse or neglect, or a surrounding community in which violence or abuse may be the norm.

“This is definitely a safe place for these kids to be and for many of them, that may be the primary thing,” said Susan Laughlin, Contra Costa County Cooperative Extension director who oversees the Oakland 4-H ASAP.

Both 4-H ASAP and the 4-H-administered school-age child care (SACC) program, located in 100 sites in 13 California counties, are examples of how 4-H has begun to serve increasingly urgent needs — those of providing quality after-school care and educational enrichment, particularly to at-risk kids (see California Agriculture, December 1994).

In fact, UC Cooperative Extension (UCCE), with its emphasis on extending UC expertise out into the community, may well prove a model for other UC outreach programs in areas such as after-school care.

“It's a very powerful model,” said Charles Underwood, assistant director of the UC Urban Community School Collaborative, which coordinates outreach projects, linking UC with local schools and communities. One such project is UC Links, an after-school program which engages children in computer and telecommunications activities

UC Links was developed by UCSD communications professor Michael Cole to provide elementary and middle-school children, many of them from poor neighborhoods, with an opportunity to learn more about an increasingly important element of our society — technology. Now on three campuses, it is expected to expand to all nine campuses by fall 1996, Underwood said. One of UC President Richard Atkinson's stated goals is to use University resources, including community-based programs like UC Links and 4-H ASAP, to increase the number of underrepresented students who qualify for the University and to improve the life chances of all California's young people.

The 4-H ASAP was started in 1988 by Los Angeles County Cooperative Extension in conjunction with the local housing authority. The program's success there — serving 1,200 children at 24 sites — prompted the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development to fund similar projects in Oakland, Kansas City and Philadelphia. In Oakland, HUD provided $1 million for a public-private partnership led by UCCE, PG&E, the Oakland Housing Authority and the California 4-H Foundation. Through the Foundation's efforts, corporations have contributed more than $100,000 to date, including equipment for an on-site computer learning center.

“There is an urgent need in the public housing community for programs that give kids a reason to say no to gangs,” said Sharon Brown, director of resident and community services at the Oakland Housing Authority. “Studies show that youth who have weaker family structures, witness violence in their own families or in their environment, and who have low self-esteem, tend to be joining those gangs. We're fighting those risk factors as hard as we can.”

For UCCE, principles employed in 4-H, such as hands-on educational activities under the guidance of caring adults, seem ideally suited to after-school enrichment programs.

“What we're doing is exactly what 4-H did 75 years ago when it first started. We're helping communities by helping kids,” said Sharon Junge, 4-H youth advisor for Placer and Nevada counties.

Junge is an advisor to 4-H SACC, which was started in the 1980s in California as part of the National Cooperative Extension's “Youth at Risk” program. While the after-school program is open to anyone, from 40 to 50% of participants are considered at risk — poor, abused or neglected, in the program because of a court order, or, increasingly, children with special needs, such as those born with fetal alcohol syndrome, Junge said.

The SACC now serves about 4,700 children aged K-eighth grade in 13 California counties. Sites are located on school grounds. Unlike many other after-school programs, SACC provides up to 10 times as much contact time with adults in structured activities such as hands-on science or arts and crafts projects supervised by 4-H trained adults or teenagers. Some projects focus on basic skills such as learning to prepare snacks, tie shoes or tell time, Junge said.

“People assume (the kids) are getting it at home. Many kids aren't,” said Junge, who said they have had students unable to tell time even in the fourth and fifth grade.

In addition, SACC offers children the opportunity to interact with adults in a structured program, sometimes over several years. Some SACC participants have been in the program 5 to 6 years, she said. “You really have a chance to make a difference in these kid's lives.”

In a recent survey of SACC sites, including 11 in California, administrators found that SACC programs helped children improve in several areas of their lives — including social interaction, academic performance and cooperative behavior.

The California portion of the survey evaluated 1,138 children aged 4 to 14. Those asked to evaluate the students were directly involved in their care, including SACC teachers, classroom teachers and principals. About a third to a quarter of children surveyed were found to have improved socially and academically over the year, with one-third of the students earning better grades. Teachers indicated that they felt about 7% of students had avoided being held back a grade, which they attributed to SACC involvement. In addition to boosting a child's self-esteem, avoiding grade retention also saves tax dollars. The survey found that the cost of repeating a year of school averaged about $3,852 for school districts surveyed.

School-age child care programs such as SACC and ASAP have provided powerful models for UC outreach to underserved communities, and added to the wealth of knowledge being accumulated in the area of child development

“It demonstrates the benefits of school-age child care on children's health and social and academic behavior,” said Joan Bissell, senior lecturer in education at UC Irvine.

-Editor