All Issues

Growing a world class institution

Publication Information

California Agriculture 47(4):27-32.

Published July 01, 1993

PDF | Citation | Permissions

Abstract

From its earliest days until now, University of California agricultural scientists have helped to shape and develop California agriculture. As society has changed, university research has continually expanded and diversified. Today's challenges are more complex than ever, but university researchers continue their long tradition of productive service.

Full text

In 1868, when the University of California was established as a land grant institution, California was still a raw, undeveloped land, its scanty population widely dispersed, its economy based largely on mining and an agriculture comprised mainly of livestock and dryland grain ranching.

The founders of the University could scarcely have imagined the California of today, but they knew they were building an institution for the future. Little did they know that the influence of that small college in Berkeley would eventually spread across the world.

Under the Morrill Act, signed by President Lincoln during the Civil War, states could use income from grants of federal land to fund public institutions of higher education. Emphasis was placed upon instruction in subjects that would develop stable and prosperous communities — agriculture and the “mechanic arts.” Thus, the University of California's first official department was the College of Agriculture.

The department had a shaky beginning. The first Professor of Agriculture, Ezra S. Carr, was ill-qualified for serious scientific work. Worse, he became involved in a political controversy that threatened relations between the Legislature and the university. In 1874 the Board of Regents dismissed him.

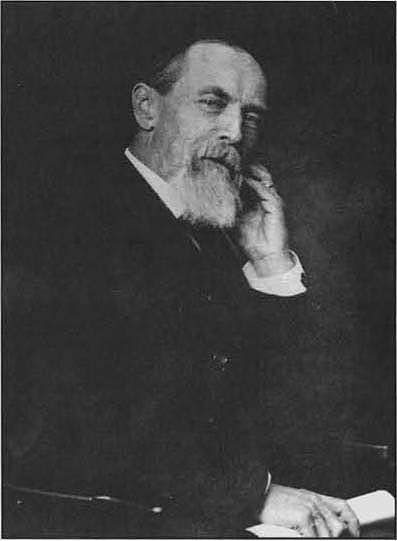

The real founder of the College of Agriculture — and UC's Agricultural Experiment Station — is considered to be Eugene Woldemar Hilgard, a respected soil scientist invited to take Carr's place. Born and educated in Germany, with wide experience in the American Midwest and in Spain, Hilgard turned out to be uniquely suited for his 30-year career at UC. He laid much of the groundwork for the state's phenomenal development in agriculture.

Best remembered for his work in soils, Hilgard helped to inventory the state's diverse soils and taught farmers to better understand them. Under his supervision, soil maps were produced for the first time for many California counties, and his research showed that soils in semi-arid climates could be remarkably productive with scientific management.

Hilgard believed in California's potential to develop a great winemaking industry, and his second greatest research effort was in this field. In 1880, the Legislature created a Board of State Viticultural Commissioners and appropriated $3,000 annually for viticultural research. For the next 15 years Hilgard supervised fermentation studies at Berkeley, amassing mountains of scientific data.

Portrait of Eugene Woldemar Hilgard, professor of agriculture, dean of the College of Agriculture, and director of the California Agricultural Experiment Station, 1875–1905. Photo from the Bancroft Library Archives, UC Berkeley.

Another important function of the agricultural experiment station was the evaluation of experimental crops for California conditions. After the 1887 Hatch Act provided a more secure and permanent basis for agricultural research, Hilgard oversaw the expansion of test plots at Berkeley to several outlying field stations. The 1890s also saw the beginnings of university research in entomology, pest control and plant diseases.

By the time Hilgard retired in 1905, the university's strength in the agricultural sciences was nationally recognized, and with a rapidly developing California agriculture, the Legislature generously supported agricultural research and education. Subsequently, the university gained several important new facilities, under the direction of Edward J. Wickson, second dean of the College of Agriculture and longtime editor of the popular statewide weekly agricultural journal, Pacific Rural Press.

Intense lobbying by dairy farmers and others brought about passage in 1905 of a State Farm Bill. Under its terms the Legislature appropriated $150,000 for the university to acquire at least 320 acres of “first-class tillable soils” for a demonstration farm, research center and practical agricultural school. The next year, an award-winning 776-acre stock and grain ranch near Davisville, not far from the state capital, became the University Farm. Its first facilities included a livestock judging pavilion, dairy barn, and creamery. In fall 1908, several short courses for farmers were offered, ranging from poultry husbandry to horticulture. In January 1909, farm boys began attending a 3-year Farm School, taking classes in such subjects as dairy management, farm mechanics and farm accounting.

Also in 1905 came legislative approval for a citrus experiment station and plant pathology laboratory for Southern California. In 1906, this station was established on the slope of Mt. Rubidoux near Riverside to focus on cultivation practices and the improvement of citrus varieties. In 1910, another research station opened at Meloland in the developing Imperial Valley for work in general agronomy.

By this time irrigation had begun to alter the face of California. Large 19th century ranches were being divided into smaller farms, and promotional literature distributed by railroad companies and land speculators feted the rich possibilities of California fruit farming and other specialty crops. Newcomers came in droves.

In 1912, Thomas Forsyth Hunt, a well known agricultural scientist and administrator in the east, became the third dean of UC's College of Agriculture. His term saw rapid physical development of the university, expansion of agricultural instructional and research programs, the founding of the Agricultural Extension Service, and the upheavals of World War I and its aftermath.

Hunt brought in competent new faculty to head the new divisions of tropical agriculture, pomology, forestry, landscape and floriculture. He also invited B. H. Crocheron to help organize the California Agricultural Extension Service in 1914.

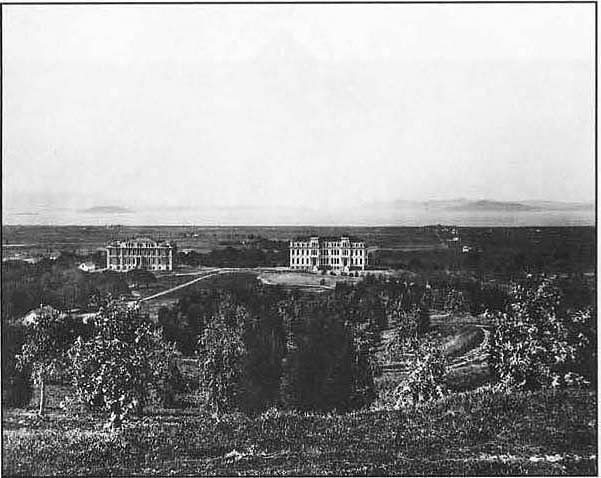

View of the grounds at the University of California, Berkeley, about 1880. South Hall, left, was the first building completed and housed the College of Agriculture in its basement. In the distance is San Francisco Bay. Photo from the Bancroft Library Archives, UC Berkeley.

Elwood Mead, a respected irrigation engineer, was appointed to lead a new division of rural institutions. Both Hunt and Mead believed that the principles of “social engineering” could be applied to shape a better rural society in California. Thus, Mead took a leadership role in a model land settlement venture sponsored by the state in 1917. In two planned colonies — Durham (Butte County) and Delhi (Merced County) — the California Board of Land Settlement offered generous loan terms for the purchase of small farms, while the university contributed technical assistance in farm management. Despite apparent initial successes, these colonies folded in the aftermath of the war, when the agricultural economy, made suddenly prosperous by wartime demand, collapsed in the 1920s.

The Agricultural Extension Service blossomed under the direction of Crocheron, who oversaw the expansion of Extension work into nearly every California county. Farm advisors, specialists and home demonstration agents, bringing new knowledge and improved methods to farmers and their families, worked to increase farm productivity and to enhance the quality of people's daily lives. Extension's 4-H youth program also brought thousands of boys and girls into an educational “project” system to teach them agricultural and homemaking skills.

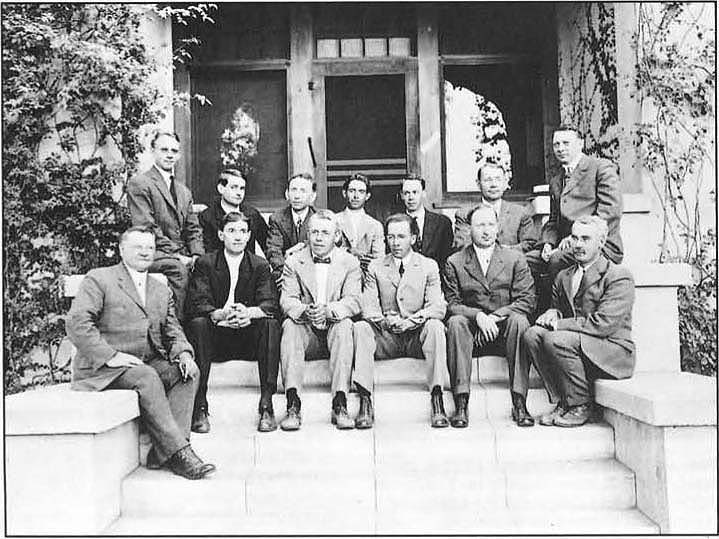

Original staff of the Citrus Experiment Station at the Rubidoux site, July 11, 1916. At front left is H.J. Webber, director. Photo from UC Riverside.

One result of the agricultural depression following World War I was a clearer recognition that farming success depended not only on productivity but on an understanding of marketplace demand and supply. Research in agricultural economics got a boost with passage of the Purnell Act in 1925. UC agricultural economists began a series of crop-and-price outlook studies for all of California's major commodities, extending their information to farmers in dozens of meetings across the state.

In 1928, A. P. Giannini, president of the Bank of America, gave the university $1.5 million to establish a research institute specializing in agricultural economics. This endowment funded construction of Giannini Hall on the Berkeley campus and established the Giannini Foundation, now known worldwide for excellence in agricultural economic research.

Succeeding T. F. Hunt as Dean of Agriculture in 1923 was Elmer P. Merrill, a scholarly botanist who oversaw a period of steady growth in the College.

Claude B. Hutchison became the fifth dean of the College of Agriculture in 1930. In the early 1920s Hutchison had overseen the reorganization of academic work at Davis when the University Farm was officially transformed into a branch of the College of Agriculture. Now, he would lead the statewide college through the depression, World War II, and California's spectacular postwar growth.

In 1930, the Regents also created a branch of the College of Agriculture in Southern California, which included the Citrus Experiment Station at Riverside and a section of the College of Agriculture at UCLA. The 14-acre laboratory-orchard at UCLA supported research projects in the production and handling of subtropical fruit crops and became preeminent in the horticultural sciences.

Despite the stringencies of the depression, agricultural research advanced. Soil and water investigations and plant breeding activities continued to improve California's cultural practices and crop varieties. Studies demonstrated that controlled brushland burning could be valuable in range management.

Understanding of livestock reproduction, diet and disease control increased. New, improved machinery was designed for many crop operations, including mechanical rice harvesting and drying, and sugar beet planting and thinning. Food scientists worked on food safety and quality, improved dairy products, the use of carbon dioxide and other gases in fruit storage, and new uses for surplus commodities.

Although World War II put much university research on hold, many advances in science fueled by wartime research turned out to have significant applications in agriculture. Chemical pesticides developed for wartime uses, for example, contributed to the enormous gains in agricultural productivity during the 1950s. But both postponed and new agricultural research also gained impetus from the Legislature's Agricultural Research Study Committee, which in 1946 held hearings throughout the state to solicit ideas on research that could help improve the production, processing and distribution of California agricultural products. Based on the committee's report, the Legislature in the late 1940s appropriated large amounts of money for new university facilities and new staff.

Academic reorganization reflected the huge postwar population influx into California, and a building boom changed the faces of campuses. Programs at Davis expanded to fill blocky new buildings, and the Citrus Experiment Station at Riverside in the 1950s became a full-fledged university campus, while agricultural programs at UCLA were phased out as population growth began to push agriculture out of L.A. County. Between 1951 and 1968 the university's agricultural field station network expanded to 10 sites across the state to serve regional research needs.

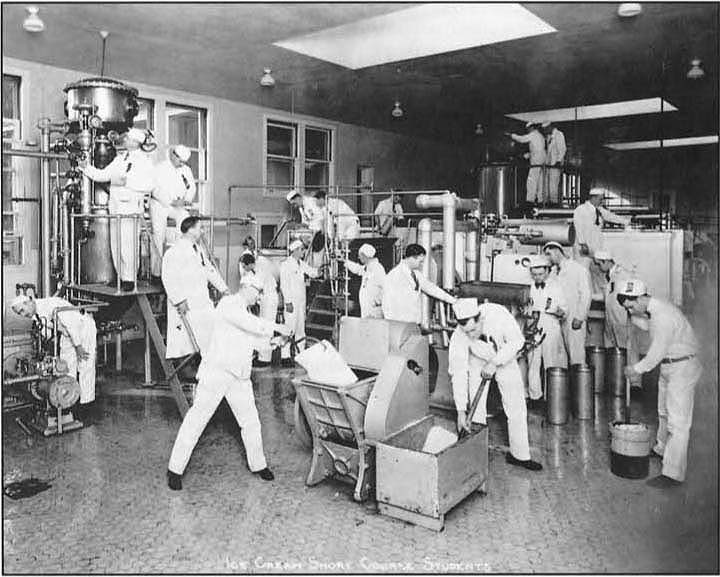

Ice cream short course at the branch of the College of Agriculture, Davis, about 1925. Photo from the Shields Library Archives, UC Davis.

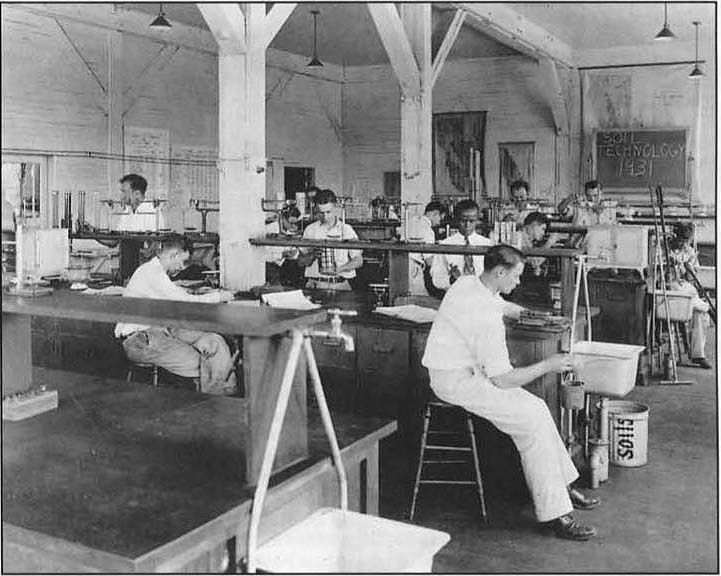

Soils laboratory at the branch of the College of Agriculture, Davis, 1931. Photo from the Shields Library Archives, UC Davis.

After Hutchison's retirement in 1952, chief university administrators for agriculture in the expansive 1950s and 1960s were Harry R. Wellman, Daniel G. Aldrich and Maurice L. Peterson. Generous state and federal funding supported agricultural research, which grew increasingly sophisticated with new instrumentation.

The many research accomplishments of the period included continuing advances in soil nutrition studies; revitalization of the strawberry industry through development of better varieties; control of the spotted alfalfa aphid devastating California fields in the 1950s; development of a safflower industry; the near-total elimination of brucellosis in California dairy herds; establishment of an environmental toxicology laboratory; and development of labor-saving machines to handle the tedious work of field and orchard cultivation and harvesting.

The great success of the mechanical tomato harvester in the mid-1960s caused controversy over the displacement of farmworkers, but advocates of mechanization insisted that new technology was the only means to retain a processing tomato industry in California.

By the late 1960s, previously ample funding for agricultural research began to decline, and the social turmoil of the 1960s contributed to more cuts in the university budget. In 1968 James B. Kendrick became vice president of the statewide Division of Agricultural Sciences, and despite competing demands for more limited research funds, his 18-year tenure saw new emphasis placed on environmental studies, biotechnology and genetic engineering, and multidisciplinary problem-solving teams.

Among the most successful university initiatives of the 1970s was the Integrated Pest Management Program, established formally in 1979 to conduct research that might help minimize use of agricultural pesticides. Other ecologically oriented programs included investigation of problems in California's Delta; joint efforts with governmental agencies on salinity and drainage in the San Joaquin Valley; the Mosquito Research Program; the Genetic Resources Conservation Program, established in 1985; and continuing activities of the Water Resources Center and the Wildlife Resources Center.

Cooperative Extension (formerly the Agricultural Extension Service and officially renamed in 1974) began several new thrusts as well: the Expanded Food and Nutrition Education Program, starting in 1969, aimed at low-income families; new programs in farm personnel management and farm safety; the Small Farm Center at UC Davis, founded in 1978; development in the 1970s of the Sea Grant Extension program to address marine resources concerns; and the Integrated Hardwood Range Management Program in 1986.

In the 1980s much basic research in biotechnology was undertaken by UC scientists to understand the mechanisms of gene expression and to explore methods of genetic manipulation. Agronomists and pomologists worked on integrating conventional and molecular genetics for developing disease resistance and salt tolerance in field and orchard crops, while others sought to enhance nitrogen fixation in legumes and other crops.

The increasing complexity of many agricultural policy issues brought about new “task force” approaches to such subjects as international marketing and world hunger. In 1985, the university established the Agricultural Issues Center at UC Davis to conduct multidisciplinary, policy-relevant research on western economic and natural resource issues. Some of the center's early activities included analysis of the impact of chemicals on the food chain and of the implications of increasing urbanization in the Central Valley.

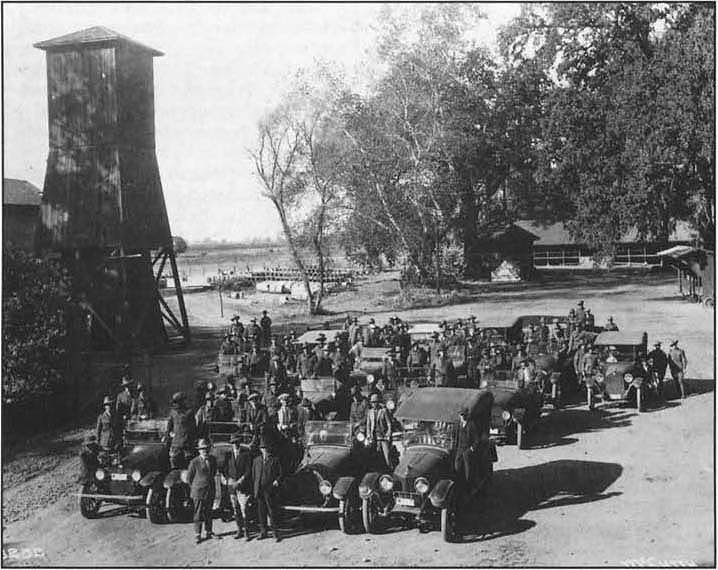

Field trip to the Durham colony by Australian soldiers studying at the University Farm about 1920. Photo from the Bancroft Library Archives, UC Berkeley.

By the mid-1980s, public awareness of environmental degradation led to widespread discussion about alternatives to conventional agricultural practices. In 1986, the division began a pioneering Sustainable Agriculture Research and Extension Program (SAREP) to study the long-term effects of soil, irrigation and pest management practices. To complement these efforts, the College of Agricultural and Environmental Sciences at UC Davis established in 1991 a 300-acre research farm for a 100-year experiment comparing conventional and alternative agricultural methods.

Under the leadership of Vice President Kenneth R. Farrell, appointed in 1987, the Division of Agriculture and Natural Resources has remained responsive to state needs, even as it examines ways to best use limited resources to meet future challenges.

While the California of the 1990s differs greatly from that of the 19th century, the University of California remains a dynamic institution that reflects and shapes the times in which it serves. As thousands of visiting scholars and students can attest, the fame of its agricultural research system — a source of enlightenment and progress for 125 years — reaches across the entire world.