All Issues

Urban agriculture and food disparities

Publication Information

California Agriculture 71(3):103-105. https://doi.org/10.3733/ca.2017a0039

Published online September 13, 2017

PDF | Citation | Permissions

NALT Keywords

Summary

Working at the intersection of technology, civic society and sustainability to build food security and community-university connections.

Full text

Disparities in access to food have many dimensions. A “food desert” doesn't mean just the lack of a nearby supermarket. Income, education, environmental quality and political power all also influence who has access to nutritious food and who doesn't.

Urban agriculture offers multidimensional solutions to the multidimensional problem of food disparities. A community garden can be an additional source of food, but also a meeting place, a gateway to education and a foundation for community organizing.

The Global Food Initiative's Urban Agriculture and Food Disparities subcommittee is working on ways to help realize these diverse benefits. It is supporting mapping projects to identify needs and opportunities for urban agriculture; studies to improve understanding of how urban agriculture contributes to meeting food needs (see Rabinowitz Bussell et al., page 139); and demonstration garden spaces that provide venues for innovation, experimentation and the exchange of ideas among students, researchers and community members.

Maddy Luthard from UC San Diego Roger's Community Garden leads a worm composting workshop at Ocean View Growing Grounds, in San Diego. In addition to being a source of food, community gardens can provide sites for community organizing and educational programs.

A common theme to the projects, said subcommittee member Keith Pezzoli, director of the UC San Diego Urban Studies and Planning Program, is the integration of sustainability science with applied fieldwork — co-inspired and co-led by researchers and community members. Through community-university collaboration, the participants are exploring how best to couple human and natural systems in an integrated socio-ecological approach. Green technology, equitable civic engagement, and new means for mapping and sharing knowledge are all key.

“We're merging three types of infrastructure: green, civic and cyber,” he said. Here are two examples:

Mapping vulnerabilities and opportunities

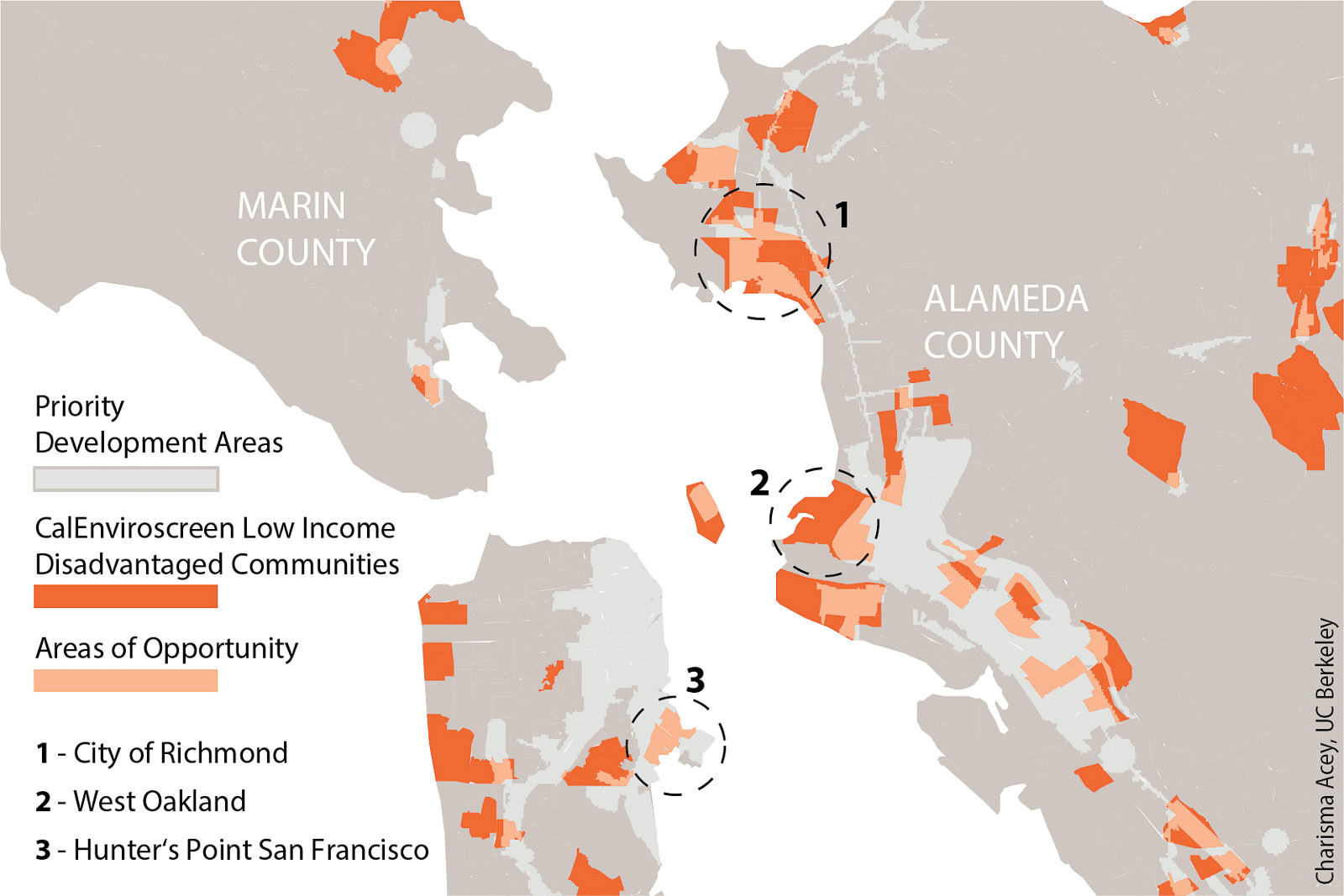

Charisma Acey, professor of city and regional planning at UC Berkeley, led a GFI-funded project to map “Food Opportunity Zones,” with a focus on the Bay Area city of Richmond (unpublished data). The zones are identified as the intersection of food insecurity (defined by variables like scarce food retailers, poverty and low environmental quality) and urban agriculture opportunity, such as properties that cities have designated for food production under California's 2013 Urban Agriculture Incentives Zone Act, which provides tax breaks to owners of urban parcels used to grow food.

The result is a map that highlights areas for investment in urban agriculture initiatives — and a mapping methodology that can be applied elsewhere in the state and across the country, especially where concerns about food justice are significant.

Circles in the map below highlight three prime “Food Opportunity Zones,” areas where factors associated with food insecurity — such as poverty, scarce food retailers and low environmental quality — overlap with opportunities to develop urban agriculture.

The rooted university

At Ocean View Growing Grounds, a community garden in a low-income neighborhood in southeastern San Diego, the GFI is helping to fund the establishment of a neighborhood community center built around food, nutrition and the environment. The project — a partnership of UC San Diego's Bioregional Center for Sustainability Science, Planning and Design and a local nonprofit organization, the Global Action Research Center — is designed to be an example of the “rooted university,” a platform for building connections between community members and the students, staff and faculty of the university.

Above and right, a soil workshop at Ocean View Growing Grounds, a community garden that serves as an example of the “rooted university,” a place for building connections among community members and university students, staff and faculty.

“It's the place where science and the residents come together,” said Pezzoli.

Pezzoli and Zack Osborn, a UC San Diego research associate, plan to extend to Ocean View Growing Grounds a program already established at Roger's Community Garden on the UC San Diego campus.

There, UC San Diego students experiment with new ways to bring technology to gardening — installing digesters to produce biogas from campus food waste, for instance, and incorporating small-scale aquaculture systems into the garden, utilizing nutrients in the fish waste to grow plants. Both involve sophisticated sensors and control systems, Osborn said, and offer challenges to science and engineering students who might not be interested in old-fashioned manual vegetable cultivation.

Bringing that energy to a neighborhood garden, Pezzoli hopes, will foster an exchange of ideas between the community and the university.

“The experimentation happening on campus gets connected to local neighborhoods,” he said. “This enables the university to be more rooted in the neighborhoods, creating a bi-directional flow of ideas and knowledge that inspires innovation and problem-solving.”

—Editors